See part one of this series here.

In this article, we’ll dive into items 12-24 on what you should NOT be doing if you want to develop high level pitchers.

- Weighted Baseballs are More Stressful on the Arm

For starters, if you’re in the anti-weighted baseball group make sure your son does not pick up anything that does not weigh exactly five ounces. Throwing things like tennis balls, softballs, dodgeballs, rocks, whiffle balls, snowballs, and footballs could seriously put them at risk for getting hurt.

(Hint: Throwing balls that do not weigh exactly five ounces is perfectly okay.)

Now that we got that out of the way, let’s talk about what classifies as a “weighted baseball.” For one, saying “weighted baseballs” are bad is meaningless because any ball that has some sort of weight is a weighted baseball. How did we figure out that the five ounce one was the safest? Why does adding (overload) or subtracting (underload) an ounce from the ball all of a sudden make it dangerous? For all we know, the five ounce one seems to do the most harm…

Stress is NOT bad. We need stress in order to create specific adaptations that supercede our previous skill level.

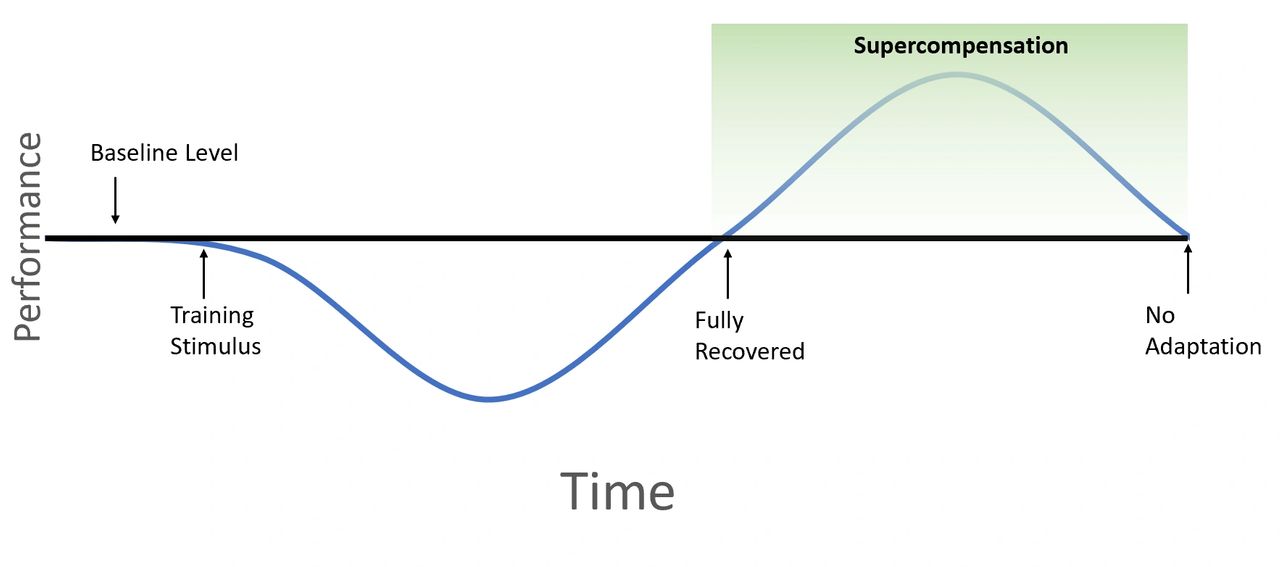

The overarching argument against weighted baseballs is some form of they are more stressful and thus more dangerous to throw with. Before we get into that argument, I think we need to understand the role of stress. Stress is NOT bad. In fact, we need stress in order to create specific adaptations that supercede our previous skill level. This process is called supercompensation and was made popular through Hans Seyle’s General Adaptation Syndrome. When a system is placed under conditions of stress, the fitness level initially decreases. Supercompensation happens when the system has been given adequate rest to recover and develop a new fitness level that supersedes the previous baseline. These positive physiological adaptations are what we are chasing as coaches and athletes. If we are not stressing the system, we are not able to create these adaptations and improve. Thus, understanding the dosage, timing, and method of applying stress becomes the better question (which is a really good one, by the way).

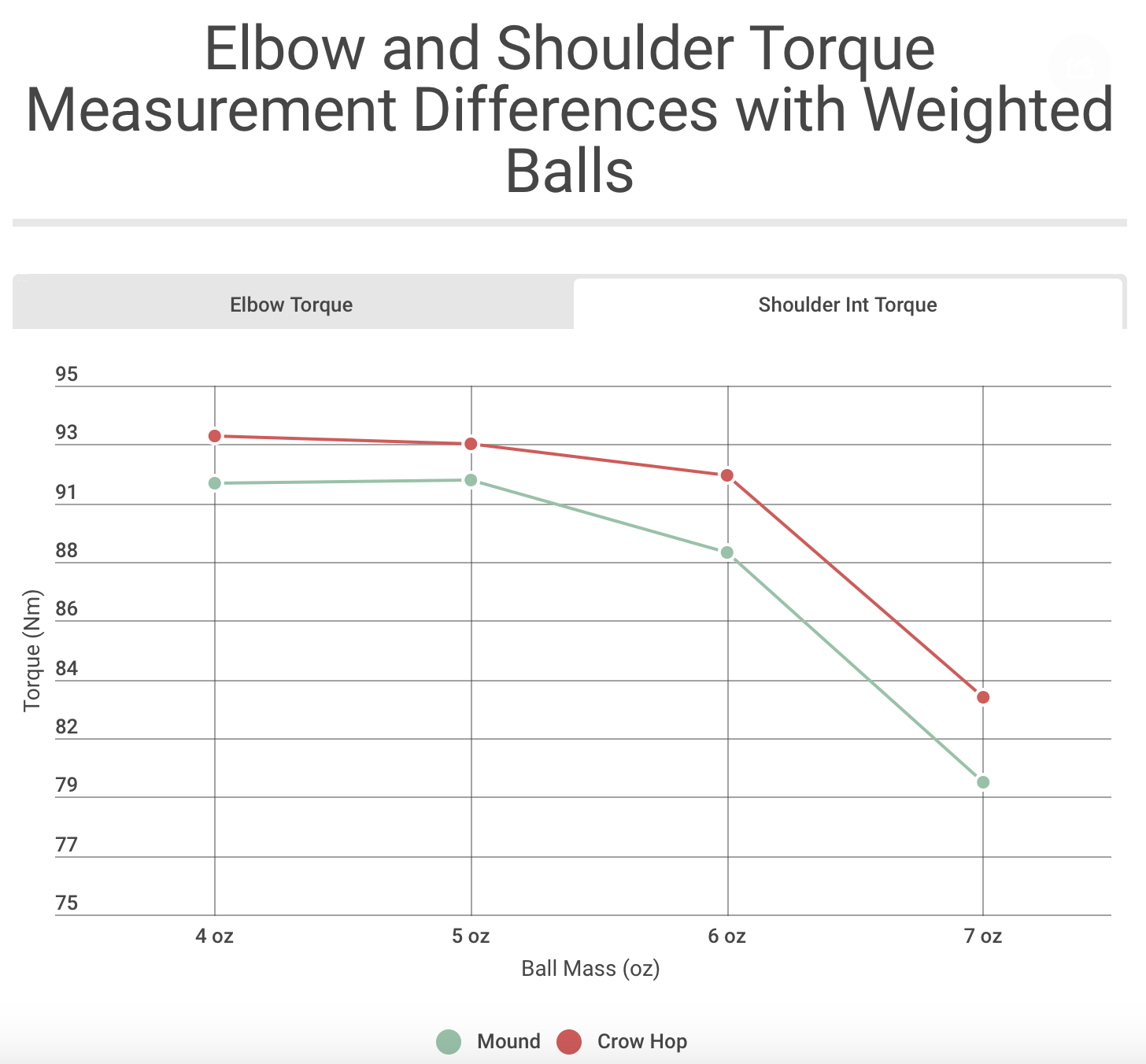

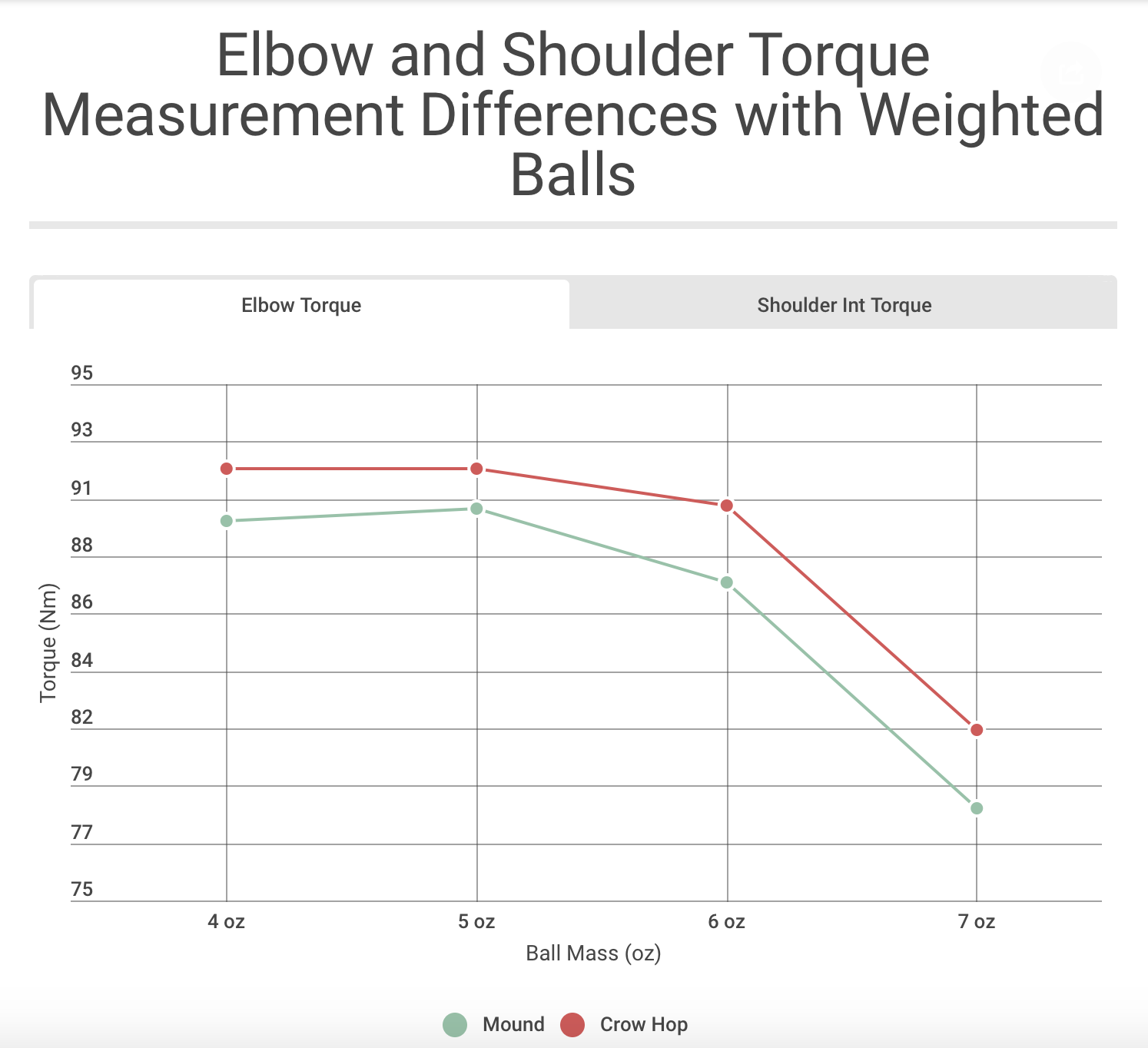

While we now understand that stress isn’t necessarily bad, it is worth looking at comparisons of stress levels between different weighted baseballs. Driveline Baseball has done research that compares the peak shoulder internal rotation torques and medial elbow torques for baseballs 4 through 7 ounces. Their findings are below:

What you’ll notice is the peak torque levels actually significantly decrease when the ball weight increases. This is contrary to what most people think about overload implements – even though we know a lot of NFL quarterbacks have had success slinging 14-16 ounce footballs without needing elbow surgery. If anything, the baseballs that might be “more stressful” to the system are the underload baseballs.

At the same time, using a cookie cutter weighted baseball program is not your fast track to adding 5-10 mph (if anyone offers you a program and guarantees you x mph, don’t walk away – run). Using weighted baseballs does not mean you are automatically going to gain velocity. Weighted baseballs are nothing more than a tool that you should have in your toolbox as a coach. Some people might really benefit from them and others may want nothing to deal with them. As a coach, you need to be able to assess each athlete and find the lowest hanging fruit before you dive into an aggressive weighted baseball program. The best programs are the ones that do a lot more than the run ‘n gun weighted ball fun stuff that you see on Twitter (i.e. proper warm ups, recovery, building throwing capacity, developing a quality strength program, hydration, nutrition, etc.).

Weighted baseballs are not bad. They are a tool.

To sum it up: Weighted baseballs are not bad. They are a tool. If used correctly, they can be a great way to build high level movements that improve velocity, command, and arm health (see research for more on this). If you use them like an idiot (i.e. see study where kids players were making max effort throws with two pound balls), you’re probably not going to get better.

- Mound work is more stressful than flat ground work

In baseball we have this myth that throwing off of a mound is more stressful than throwing off of a flat surface (apparently the idiots who created baseball forgot throwing off an elevated surface is bad). As a result, a lot of coaches will have pitchers work from a flat surface when practicing their pitches or delivery between outings. While there may be a time or place for flat ground work, it’s not quite accurate to say flat ground work is less stressful than mound work.

Driveline Baseball recently published a case study where they took elbow torques of mound throws, flat ground throws, and compared the two. When they normalized for velocity, what they found was flat ground throws were actually more stressful than mound throws. They hypothesized that this was the case because of a lack of movement efficiency from a flat ground throw since we know stress does not have a linear relationship with velocity. Randy Sullivan and the Florida Baseball Ranch also investigated this myth at the 2019 ABCA Convention and found in their case studies that the average torques from mound throws and flat ground throws were nearly identical.

A 2014 research article reported similar findings saying, “Flat-ground throwing at even the shortest distances had similar biomechanical loads compared with pitching from the mound, yet at significantly lower ball velocity. This illustrates the mechanical advantage and increased efficiency of throwing from a mound.”

If pitches are being executed off of a mound in a game, you are doing a disservice if all of your work between outings is off of a flat ground.

As for the application, using the safety argument for flat ground throwing doesn’t really hold up against the research we have. Flat ground work can be a convenient way to get some work in if you don’t have access to a mound. However, the game is the most important thing. If pitches are being executed off of a mound in a game, you are doing a disservice if all of your work between outings is off of a flat ground. Too much flat ground work can disrupt the timing of your delivery and create movements that don’t scale off of a mound. As Sullivan says best, “Anything you overindulge in can corrupt you.” There can be a time and place for flat ground work, but it must be managed so the most important work is being done off a mound. Mound work is going to drive greater movement efficiency and is going to create the most game-like environment so you can better transfer your training to the playing field.

- Velocity doesn’t matter

To start this one off, we need to detach ourselves from baseball and ask ourselves this question: “In what sport would we want to give our opponents more time to make decisions?” I don’t know about you, but I don’t think there’s a single sport out there that would want their opponents to have more time to make decisions. When it comes to pitching velocity, this is exactly what we’re doing – we’re giving the batter less time to determine whether they should swing or not. If you don’t think this is a competitive advantage, don’t waste your time reading the rest of this.

All opinions aside, we know that velocity plays at the big league level. Offensive production falls off of a cliff when the radar gun starts lighting up numbers in the mid to upper 90s. Toronto Blue Jays General Manager Ross Atkins spoke about this in a Washington Post article saying, “You’re right that (front offices) are obsessed with velocity, and the reason is that it works. It is definitely the hardest thing to hit. It changes approaches, for sure. You can’t hit velocity without getting geared up to attack it.”

Below are the offensive slash-lines of MLB hitters in 2018 when facing four different pitch speeds.

- 92 mph: .283/.364/.475

- 95 mph: .259/.342/.421

- 98 mph: .223/.310/.329

- 101 mph: .198/.257/.214

Adding velocity also benefits your breaking ball by improving its movement profile and effectiveness off of your fastball. It’s really tough to lay off of a mid to upper 80s fastball when you’re geared up for 98 on every single pitch. On the contrary, it’s going to be easier to lay off of breaking stuff when you have a lot more time to make a decision on their best heater. If you can speed up someone’s bat, your breaking ball just got better.

While velocity doesn’t tell you whether you can pitch or not, it helps you get your foot in the door. “Velo is king, at least in the draft process, amateur ball and up into minor league ball,” said Trevor Bauer in a New York Times article. “Once you get to the big leagues, and you’re here, getting outs and stuff like that is king. But up until the big leagues, velo is king, and in the minor leagues, guys that have poor results but throw really hard get a lot more opportunities than guys that have really good results but throw 86 or 88.”

Velocity can be trained and it will improve your effectiveness as a pitcher. Believing it’s not is probably just an excuse for why you don’t throw hard. If you’re working with kids that want to take their career to the next level, you need to track, measure, and train for velocity. The average fastball velocity at the big league level in 2019 surpassed 93 mph – up from 89 mph in 2002. If you aren’t encouraging kids to move fast and let it eat, you’re playing from behind.

- Lactic Acid “flush runs”

This one was one of my favorite ones to dive into because I think all pitchers have heard some variation of a “flush run” or running long distance to “build up your legs.” I started by pulling out Episode 19 from the Elite Development Baseball Podcast by Eric Cressey. In the podcast, Eric talked about why long distance running is common with pitchers and why he thinks there are better alternatives out there. Some of the main points from the episode were:

- Lactic acid is not the cause of muscular fatigue

- Physiological adaptations are incredibly specific

- Research has shown there is not a significant amount of lactate present in pitchers post throwing

- Developing a good aerobic base is important to accelerating the recovery process between training sessions

- Maintaining an adequate aerobic base requires a low frequency and intensity

If we compare long distance running to pitching a baseball, we come up with a pretty significant contrast when it comes to energy demands, recovery intervals, and exertion levels. Using long distance running to “build up your legs” for pitching is not going to create an adaptation that is specific enough. Pitching a baseball requires the creation and dissipation of a large amount of force within a short timeframe. Long distance running cannot create these types of demands that would transfer over to throwing a baseball.

As Eric alluded to, flushing lactic acid out of your system is a myth when it comes to recovery. Dr. Stephen Osterer of Baseball Development Group did an awesome job explaining the misunderstanding behind lactic acid in his Recovery resource (well worth checking out if you’re interested in this kind of stuff). He said:

“Mistakenly termed ‘lactic acid’, lactate is a natural byproduct of anaerobic metabolism that is used as a source of energy. Lactate has been wrongfully labelled the direct cause of muscle soreness after an acute bout of exercise – a sensation mediated instead by the inflammatory process from tissue breakdown – as well as causing the deep burning feeling and acute localized fatigue. Commonly, lactate has been the justification for several post-game or exercise recovery interventions, such as flush runs of active cool downs. This is problematic for several reasons. The first is the obvious short term timeframe in which higher lactate concentrations return to normal – usually within an hour. If we are undergoing more exercise within that hour, then attempting to influence lactate concentrations may be an advantageous step. But if we otherwise have days prior to the next competition is there a need to speed up the naturally occurring process? Moreover, although a few studies have shown reductions in lactate removal following an active recovery protocol, lactate itself has not been considered a strong predictor of training recovery or return to performance.”

Using distance running for pitchers does not “clear lactic acid” (not like it’s important anyways), it doesn’t build specific adaptations to throwing, it sabotages training economy that could be put into things that would actually help you get better at baseball, and it puts you at a higher risk of getting injured (running cross country is a horrible way to get into “baseball shape”). If you understand these risks and still want to go for a 15 minute jog after your start the next day, feel free. Don’t take something out of a kid’s program that he really enjoys. However, you cannot shove long distance running down the throats of your players when we know it just doesn’t match up against the physiology.

Building an adequate aerobic base is important and should be prioritized for optimal recovery, but it’s a lot easier to build and maintain than most people think. Your training should help you throw a five ounce baseball – not run a 5K.

Feel free to check out some more thoughts from Eric on this here and some thoughts from Driveline on the same topic.

- Developing a sixth pitch

Understanding when to develop a new pitch is a really important question you need to address before allocating a huge chunk of training economy to learning that pitch. If you’re looking at adding a new pitch, you need to first understand your current arsenal. How does each pitch stack up against your competitive peer group in terms of velocity, command, and movement profile? What kind of batted balls typically occur when you throw that pitch? Does it get any whiffs? What kind of confidence do you have in it?

If you’re not sure about any of these questions, start with this one: “Bases loaded, two outs, 3-2 count with the game on the line – how many of my pitches would I be able to throw in this situation?” If you can’t throw any of your pitches with this kind of conviction, you don’t have a pitch. If you can only throw two of your five pitches in this situation, you don’t need to add a sixth pitch to the mix. You need to look at the three you can’t and either scrap them or work on them. I would take a guy that can go balls to the wall with two pitches over a guy that dabbles with 12.

We all have a limited amount of time. Determining how we best make use of that time is going to have a huge impact on your development on the mound. We can only allocate so much time and energy to the various things we want to work on. Find the lowest hanging fruit and work up from there. You don’t need to add a 12-6 curve, slider, and change up if you’re a freshman in high school that tops out at 69. You just need to throw the ball harder. If you find that adding a certain breaking ball or change up would compliment your arsenal without sacrificing much needed training economy in other areas, by all means go for it.

Get really good at one thing before adding something else. It’s easy to fantasize and dabble with adding a new pitch to your mix for the upcoming season. It’s tough to evaluate where you are and see if you actually need that pitch.

- Icing/Non-Steroid Anti Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs, i.e. ibuprofen)

This one is a big one in the baseball community as you’ll commonly see guys pop a few Ibuprofens before throwing and throw a couple ice bags on their arm after throwing. If this is your daily throwing routine, you should really read this next section. If Dr. Gabe Mirkin – the man who invented the RICE (rest, ice, compress, elevate) protocol – no longer advocates its use, why would we use it with our athletes?

If we look at recovery, tissue repair requires three stages:

- Inflammation (gasp)

- Repair

- Remodeling

To get to step two of the recovery process, you must go through step one. This means inflammation is not a bad thing that you should avoid – it is step one to getting you back on the field. Inflammation helps accelerate the recovery process by bringing blood, nutrients, oxygen, and other first responders to the injury site. They help clean out the damaged tissue and prepare it for the next step of the recovery phase. If you’re using ice to “reduce inflammation,” you are preventing the body from going through a necessary step in the recovery process. Icing injured tissue constricts blood vessels and limits the amount of blood flow to the injured site – the exact opposite of what your body is trying to do. Gary Reinl – one of the world’s leading experts in recovery – says it best: “You can have inflammation without recovery, but you cannot have recovery without inflammation.”

If you’re icing to reduce swelling, you are again working against your body when it comes to tissue repair. Reinl explained this in a Youtube video with Kelly Starrett – author of Becoming a Supple Leopard – saying how swelling is the end result of the inflammatory stage. Swelling is a natural phenomenon where blood vessels in the injured site are dilated. This helps open up the area so the good guys (blood, nutrients, etc.) can get in and clean up the damaged tissue. This process must run its course before getting to the repair stage. Swelling, thus, does not become the problem. The problem is the evacuation of swelling at the end of the cycle.

Swelling is not the issue – the inability to evacuate swelling at the end of the inflammatory process is. Icing does not help you do this.

This is where the lymphatic system comes in. Your lymphatic system is a series of one way bags of fluid that are designed to evacuate swelling via muscle contractions. The last part of that is the most important because the lymphatics is a passive system. This means if you are not actively contracting muscles around the site of damaged tissue, there is no way for the lymphatic vessels to evacuate swelling. Icing and immobilizing damaged tissue does not help accelerate recovery – it prevents your lymphatic system from doing its job. If anything, you’re increasing the likelihood for more swelling because the swelling that was already there now has nowhere to go. Swelling is not the issue – the inability to evacuate swelling at the end of the inflammatory process is. Icing does not help you do this.

Reinl also made a point to mention icing will make you feel good in the short term because it cuts off the signal between the muscles and nerves. This is why using NSAIDs like Ibuprofen or Aleve can be a misleading treatment option for your nagging arm. When using anti-inflammatories, you shut off the signal completely. Your nervous system is designed to protect you and keep you out of danger. If you inhibit your body’s ability to let you know when there is pain, you run a great risk of hurting yourself and creating long term issues. If you have pain, Aleve and ice is not going to help solve the issue. It’s going to mask the actual problem that needs treatment. If you have pain, ditch the pills, ice packs, and get assessed by a professional who has experience dealing with overhead throwing athletes.

Key Takeaways:

- Inflammation is not bad. It is the first step of the recovery process that must be completed before steps two (repair) and three (remodeling).

- Icing prevents the inflammation process by constricting blood vessels and limiting the amount of blood flow to the injured site – the exact opposite of what your body is trying to do.

- The lymphatic system is a passive system that works to evacuate swelling through muscle contractions.

- Icing and immobilizing an injured area prevents the evacuation of swelling and can actually create more swelling.

- Icing an injured site blocks the signals between muscles and nerves making you feel good temporarily.

- NSAIDs completely block the signal between muscles and nerves.

Reinl also did a podcast with Eric Cressey about this subject. See their interview here for more information and alternative methods to icing for recovery.

If you have damaged tissue, don’t ice it, immobilize it, suppress it with anti-inflammatories, or do anything else that would prevent it from healing. You’re better off just getting out of the way and letting your body do what it knows how to do best. If anything, use the old advice of “just walk it off” and help your lymphatic system help you.

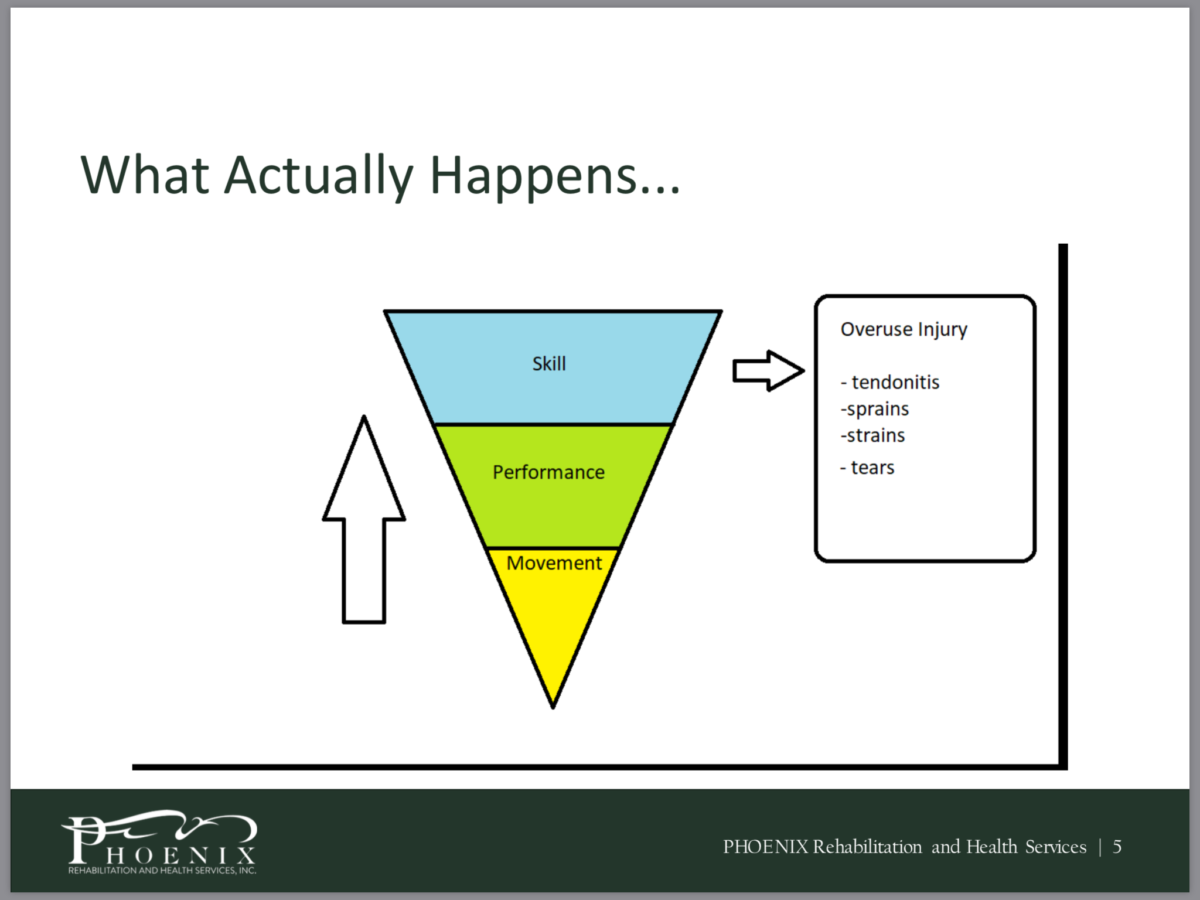

- No pain, no gain

In the Phoenix Rehabilitation presentation from part 1 of this series, Monica Johnson shared a statistic that really bothered me as a coach: “46% of injured adolescents report being encouraged to play through arm pain.” When we encourage kids to play through pain so we can win some meaningless travel baseball tournament championship, we are putting an adrenaline-infused kid at serious risk. We’re basically telling them to ignore the body’s message to us that something is wrong. We’re encouraging them to play through something that should be addressed. When we do this, kids are going to be more likely to hide pain from us in the future because they know we’ll be upset when we have to pull them from the lineup. When we create these kinds of associations with pain, we lose the ability to protect our athletes when they’re actually hurt.

As coaches, we need to create transparency with our athletes where they should comfortable speaking up if they are in pain. We need to create relationships with physicians who can take care of our kids and detect early warning signs for serious injuries. It’s not okay if your starting pitcher needs eight Ibuprofen to throw every seven days. It’s also not okay if your starting shortstop has shooting pain every time he picks up a baseball.

Winning baseball games should not come at the expense of the health of your athletes. “No pain, no gain” is not an acceptable answer. If there is pain, something is wrong and it must be addressed.

- Pitching to the hitter’s weaknesses over your strengths

John Wooden was not a huge fan of scouting reports. When his assistants tried to bring up the tendencies and strategies of his opponents, he didn’t pay too much interest. Wooden knew that if his teams played to the standard of UCLA basketball, it wouldn’t matter who they were playing or what they did – they would win regardless. I think this strategy could not be more applicable to a position that typically wins 70 percent of its battles. If you make good pitches and get into favorable counts, you will beat hitters a large majority of the time. This starts by understanding how to play to your strengths.

If we pitch with the intention of exposing the weaknesses of hitters, we run the risk that we get away from our strengths. If we’re facing a guy who can’t hit curveballs but out curve is our least confident pitch, it makes no sense to throw two uncompetitive breaking balls and find yourself in a hitter’s count where you have to pitch to his strength. You’re better off going right at guys with the pitches you have confidence in regardless if it’s a strength of the hitter. If your stuff sucks, that’s a whole different problem.

If you don’t know your strengths, now is a good time to figure those out. You need to have awareness for the pitches you have the most confidence in. Know what pitches to go to when you need a strike, ground ball, and swing and miss. Know which pitches play better against left or right handed hitters. You can’t become a great competitor if you don’t have a great feel for your bread and butter on the mound.

Don’t fail with your worst pitch. Go to war with your best stuff.

Images from @pitchingninja

- Two strike “waste pitches”

This is something I wrote an article about a little bit ago. Read it here to understand the pitfalls of conventional wisdom when it comes to pitching with two strikes. If you don’t want to read it, I’ll summarize it using one question: “Why would you shrink the strike zone when you’re working in the most advantageous count as a pitcher?”

Ditch the 50 foot curveballs and the four seams painted four inches off the black. Be like Greg Maddux and go right after guys.

- In Game Mechanical Cueing

Revisiting part 1, the optimal focus of attention for athletes in game situations is a specific external mindset. As a result, your language in games should encourage this kind of a mindset. If a pitcher needs to be over the rubber in a game, you as a coach need to be over the rubber with him. If you’re using vocabulary that encourages an internal focus of attention, you’re working against his ability to keep things simple and compete with confidence.

Be very careful how you talk to pitchers when they’re warming up, throwing their pre-game bullpen, between innings, or when you talk to them during mound visits. When you’re in a game, all you can do is compete with what you have that day. Sometimes everything will be working, sometimes nothing will be working, but most of the time you’re going to be constantly fighting, compensating, and making adjustments in games. Jon Lester said it best in Heads Up Baseball 2.0: If I have 30 starts in a season 5 will be with my A game, 5 will be with my C game, and 20 will be with my B game.

If we know an external focus of attention works in games, we need to teach kids how to make adjustments externally with their eyes. Instead of making them worry about their mechanics, teach them to pick up a visual that helps them make adjustments and execute specific pitches. If Sammy is walking everyone in sight, the last thing he needs to hear is he’s falling off the mound, his throwing arm is late, his front leg isn’t bracing, and he’s not following through with his pitches. If anything, the best thing you can do is get him to breathe, get locked in on a focal point, and get him to start throwing with conviction (see Building a Process Oriented Athlete for more on this).

To understand the importance of your language in games, see the excerpt below from Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik’s The MVP Machine:

Notice how Brent Strom didn’t yip the kid up about his arm action, lower half, or any other number of distractions. He instead used a little bit of humor to get the kid out of his head. Some of the best mound visits you can make won’t require a word about baseball. At that point, you have to compete with what you’ve got. Life isn’t perfect – it’s messy. Don’t miss out on an opportunity to teach kids this.

Sometimes you fix the ship, other times you patch a hole and keep pressing on. You can’t have an athlete work on a specific pattern and try to compete at the same time in a game.

This is something to keep in mind when you’re making mechanical adjustments throughout the course of a season. As mentioned before, it is helpful for athletes to internally focus on a specific movement when first learning it. This internal focus helps them get a feel for the pattern so they can practice it, master it, and eventually make it automatic. The key to this is the shift from an internal focus to an external focus. If you can’t get athletes to execute the pattern using the external focus, you’re not going to be able to use it in games. As a result, you need to be able to pick your battles as a coach. Sometimes you fix the ship, other times you patch a hole and keep pressing on. You can’t have an athlete work on a specific pattern and try to compete at the same time in a game. If your movement patterns are that bad that they’re affecting your game performance, you shouldn’t be playing games to begin with.

Don’t yip kids up when they’re already yipped up to begin with. Kids need to be in a state of mind where they’re ready to compete. If they’re worried about 69 different mechanical cues while also trying to send guys back to the dugout, you’re going to have a recipe for disaster.

- “Just throw strikes”

Tell me if you’ve heard this one before: Pitcher X is in the middle of a walk parade while everyone on his side of the field is telling him to “just throw strikes.” I mean, seriously – did you think he was trying to throw balls? Do you really think that telling him to “just throw strikes” is all of a sudden going to make him throw strikes? Better yet – do you really think a ten year old has elite command of the strike zone when he can barely walk and chew gum at the same time?

The language you use with kids is very powerful – especially when they’re young. Young athletes are constantly fighting cognitive dissonance – they want to do things that make them feel good (winning) and avoid things that make them feel bad (losing). You as a coach are going to play an important role in that because kids are going to look to you for approval in a lot of situations. When you praise and commend them, they’re going to feel good. When you scold them, they’re going to feel bad. Thus, influencing kids depends on providing reinforcement for specific behaviors. The issue becomes this: You’re going to have the tendency to reinforce skills that might play when they’re younger but don’t play when they get to the big field. Two examples of this are:

- Making hitters look stupid with horrendous breaking balls

- Beating balls into the ground and either a) beating them out or b) letting the defense kick the ball around

When we reinforce poor breaking ball habits and beating balls into the ground, we’re sending messages to kids that doing these things are good and they should be repeated in the future. However, we know butchering a curveball is eventually going to catch up to that kid and it’s either going to get killed in high school or his arm is going to suffer. We also know that beating balls into the ground is going to create a steep bat path which prevents kids from driving balls in the air with authority. Ground balls and shitty breaking balls might help you win 12U tournaments, but they’re not going to help you win when it really matters later in their career.

Giving kids who have an underdeveloped neuromuscular system the task of commanding a sphere three inches in diameter to a target 50 feet away is not an easy thing to do.

This is where “just throw strikes” comes into play. For one, we know that velocity is a significant barrier if you want to pitch at the next level. We also know that throwing strikes in youth baseball is equivalent to flipping a coin. Giving kids who have an underdeveloped neuromuscular system the task of commanding a sphere three inches in diameter to a target 50 feet away is not an easy thing to do. If we think about the movements that kids are going to make when they’re a) trying to throw the piss out of the ball or b) trying to dot up a corner, we’re going to get a significant contrast. One of those deliveries is going to build a foundation that will help kids pitch at the next level (yes, you can train velocity and command at the same time). The other one is going to create something that mirrors a robot trying to throw darts. You tell me which one you’d rather have.

We make this even worse when we throw some variation of “just take a little off and hit the zone.” What we’re really saying to the kid is: “You can’t throw hard and throw strikes at the same time.” When we create this association, we essentially put a governor on that kid’s ability to throw hard because he’s worried about not throwing strikes. This is what’s known as the speed-accuracy trade off. This refers to the relationship between performing a specific skill with precision vs. how fast we can do it. If we look at this relationship at the major league level (see graphic below), we notice that there really is no velocity trade off for command. Developing command is not as simple as just telling a kid to ease off the gas pedal. There’s a lot more that goes into it. In some cases, telling a kid to slow it down might make their command worse.

If your kid isn’t filling up the zone like Greg Maddux in 11U, don’t panic. Most kids are pretty bad at commanding the baseball simply because they don’t have the size, strength, coordination, or repetitions to figure things out. If anything, your best bang for your buck when they’re young is to develop speed. Research shows that kids ages 7-12 years old have a one-time window to develop elite speed as their skeletal structure is outgrowing their muscular structure. This creates tightly bound muscles that are very good at moving fast. If you spend these years doming up kids over their ability to dot corners, you are missing out on a huge window of opportunity to develop arguably their most important asset on the mound.

If you’re working with kids who struggle finding the zone, don’t shrink it – expand it. We know most youth hitters aren’t exactly the most disciplined in the first place. Widen the zone, give kids the freedom to move fast, and throw out worrying about the end result. USC is not panicking if your 12U strike percentage is under 65 percent. However, you will be panicking if you’re a senior in high school, you’re topping out at 72, and you’re not getting any looks because you were too busy taking a little off and just throwing strikes. If the language you use is not helping kids develop skills that will scale, you’re wasting your breath.

If the language you use is not helping kids develop skills that will scale, you’re wasting your breath.

Let kids move fast, throw hard, and create an environment where they can start to figure out how to command a ball implicitly (i.e. without a barrage of meaningless verbal cues). The messages you send kids at a young age will have a huge impact on the rest of their career. You can’t expect kids to navigate the strike zone with pinpoint precision early on. Keep it fun and let them throw fuel. You’re better off refining command as they get bigger, practice more, and refine their neuromuscular system. Command is built largely through feel. You can’t develop feel if you’re domed up about walking the entire lineup because you’re “throwing it too hard.”

- “Pull the lamp shade down”

The curveball is one of the most butchered pitches out there so I wanted to reserve some space to talk about it briefly here. Trevor Bauer does a really nice job explaining this in his Youtube pitch design video. I would highly recommend checking it out for more info on this. Below are some of his main points from the video:

*See 11:25 for curveball

- Cues like “twist it,” “pull the lamp shade down,” and “karate chop it” don’t actually describe what is going on at release and are poor ways to try to teach the pitch.

- While you want to get to the front of the ball to create front spin, you want to pronate through the pitch instead of pulling down around it.

- Pronating through the pitch helps promote a healthy deceleration pattern.

- Don’t try to manipulate this with your wrist – lock your wrist in place.

- To create front spin, lock your wrist in a supinated position so your middle finger can get to the front of the ball.

A really good question that came up in the discussion was when should pitchers start to learn a breaking ball? I think that is an awesome question that requires a lot of investigating from several different angles. From the things I’ve read and the people I’ve talked to, there really isn’t a need to showcase a spinner in games before 14 (see thoughts from Driveline). Early on, your goal should be to build a fastball that is above your competitive peer group in terms of velocity, command, and game effectiveness. Kids are going to get emotionally attached to pitches that help them win games when they’re younger. This means that they will get attached to a horseshit breaking ball that plays at 12U but won’t play when they get older.

Instead of keeping fastball mechanics and letting the grip create the movement profile, kids are going to slow their arm down and try to create movement in the wrong places (ex: creating a lot of lateral trunk tilt to get on top, dropping the arm to create more horizontal movement). This alters their delivery and can have a negative impact on the rest of their arsenal. The curveball is a complex pitch that takes time to learn and ultimately master. Giving it to kids who lack neuromuscular control and are fighting to compete against fatigue and other variable conditions in a game environment is a recipe for disaster.

With this, I think Christian Wonders provided some really cool insight on this topic on Eric Cressey’s podcast (link here). If kids show sufficient movement quality at a young age (i.e. being able to do a push up, play catch without getting a cardio workout in from chasing balls), Christian sees value in teaching kids how to spin a ball early on. We know that throwing a curveball is a specific skill that must be learned through practice. If kids haven’t learned how to spin a ball when they’re 15, 16, or 17 years old, it becomes much more difficult to learn because they don’t have the repetitions or feel for holding a supinated position.

Below are a few tips that Christian discusses in the podcast when first learning a breaking pitch:

- Teach kids how to hold the proper grip (don’t overlook this one).

- Use carefully selected cues (he uses shoot the gun to the ground) to create a top to down front spin (think 12-6 or 1-7).

- Never throw more than two curveballs in a row. Keep fastball arm speed a priority.

- Get to the front of the ball and drive late arm speed.

- Address lower half mechanics (i.e. loading/unloading the back hip) to determine if kids are physically able to get into positions where they can create the correct movement profile.

- Try to keep delivery within an imaginary tunnel to prevent kids from spinning off the pitch and creating side spin.

- Learn one breaking ball before you learn two.

Play for the long term when developing a spinner, but don’t wait until it’s too late because you’re afraid of getting hurt (hint: current research doesn’t suggest curveballs are more dangerous).

- Missing the forest for the trees

As mentioned above, your goal as a coach should be getting kids to play their best baseball at 17, 18, and into their early 20s. Your goal is not to develop the best 12U team in the world. If kids aren’t growing and developing a skill set that will help them compete at the next level, you are doing them a disservice. If you are abusing the players on your team who hit puberty first, you’re damaging their love for the game and the chance they’ll continue to play throughout high school. If you burn up your ace traveling the country at 16 years old and land him on the surgery table, you might have cost him the chance to go to a Division I school and play professionally – all for a couple of tournament trophies.

Taking advantage of kids for our short term interests must end. We cannot pitch in baseball games 12 months out of the year and expect kids to stay healthy and continue to have a passion for the game (ASMI has found kids who pitch in games more than eight months out of the year are five times more likely to get hurt). We need to build the athlete first and give kids opportunities to try out other sports before shoving one down their throat. We need to let kids experiment with other positions instead of labeling them as a “pitcher only” at 14. If Jacob DeGrom played shortstop through his junior year of college, I don’t think you need to rush your high school kids to specialize on the mound.

Most importantly, we need to be the authority figure that has the discipline to step in and tell our best pitcher that he’s reached his pitch count and he can’t pitch anymore. We need to allow time for our number one to return to mound shape instead of rushing him back for a game that he is not prepared for. We need to forget about the wins and losses and instead focus on what’s next for that kid. If what we’re trying to do doesn’t fit in the long term plan for that athlete, we cannot do it. If he does not have a long term plan, make one.

Do it the right way and play the long game. You owe it to your kids.

F

F