The week of March 9, 2020 completely changed my life forever.

On Monday, I departed for Southern California to join the 108 Performance team and begin a year-long internship program. The program represented the opportunity of a lifetime as I had the ability to learn how to train players from some of the best minds in the game, build an invaluable skill set, and interact with an incredible network of coaches. My dad and I reserved a week to make the 45 hour drive out to Irvine, CA with stops in Chicago, Des Moines, Denver, the Grand Canyon, and Las Vegas. For someone who had never seen anything west of Dallas, I was thrilled to finally see a part of the country I had never experienced before and make some really cool memories throughout the process.

What I didn’t know was the events that unfolded throughout the week of March 9, 2020 would change the course of human history.

On Wednesday, March 11, my dad and I were sitting down for a meal in a small bar and grill in Arvada, CO – located about 20 minutes west of Denver. The TV in the bar was showing Luka Doncic and the Dallas Mavericks take on the hometown Denver Nuggets in front of a packed crowd at American Airlines Center. Over the past couple of days, NBA owners had been mulling the idea of a postponing the season due to rising concerns of coronavirus (COVID-19). This evening, the Mavericks and Nuggets proceeded as they normally would for a typical game day but with understanding that things could look very different and very soon.

They just didn’t realize how soon it would be.

In the middle of the third quarter of the game, breaking news appeared on the ticker at the bottom of the screen: Rudy Gobert of the Utah Jazz had tested positive for COVID-19. Gobert had been warming up on the floor prior to Utah’s game against Oklahoma City and was showing symptoms of the flu. When word got out that Gobert had tested positive for COVID-19, NBA Commissioner Adam Silver immediately postponed the game and evacuated the Oklahoma City arena. Shortly after, Silver announced that the NBA was postponing its season indefinitely. The Mavericks and Nuggets concluded their game that evening with fans in attendance, but news of Silver’s decision got out well before it ended. I couldn’t tell you anything about that game and how it finished, but I can remember exactly how I felt walking out of dinner that night. I had a bad feeling that this was only going to be the start of something that completely changed everything we ever knew about sports.

I ended up being correct. Silver’s decision was the tipping point that sent everything over the edge.

The following day on March 12, the NCAA made the shocking decision to cancel its annual March Madness tournament – which accounts for over 80 percent of the organization’s annual revenue – for the first time since 1938 along with all remaining winter and spring sports. Right behind them were the MLB, NHL, and MLS. Less than 24 hours since Gobert’s positive COVID-19 case and Silver’s decision to shut the NBA down indefinitely, all professional and amateur sports in North America had been completely shut down. The next day I would find out that 108 Performance was going to follow suit and close its doors to prevent the spread of the virus. Yes, that meant that I had just packed up my life and driven over 40 hours across the country only to find out that the facility I just secured my dream internship at was now closing its doors indefinitely with experts predicting a shut down that could last up to several months.

Talk about a change in events.

When I started at 108 on Monday, I wasn’t going to be learning how to train athletes. I was going to be learning how to navigate a small business in the midst of a global pandemic with significant financial ramifications. Well, we were going to learn. Last time I checked no one really had an instruction manual on how to navigate a global crisis fueled by a microorganism in which we knew very little about.

We do know a lot about epidemics, however.

Viruses like COVID-19 may be unpredictable in their appearance, evolution (flu vaccines are educated guesses), and how they infiltrate a population, but how and why they behave is rather predictable. Malcolm Gladwell talked about this in his best-selling book The Tipping Point where he explained the conditions that must be met in order for something to take hold and spread. For a virus to transform from a seasonal scare into an epidemic, three critical elements must be met:

- Contagiousness

- The virus must be able to spread from one person to another through direct or indirect contact.

- Little causes have big effects

- The virus does not start with a large following – it grows from one case and multiplies as it infects a larger portion of the population.

- Epidemics can rise or fall in one dramatic moment

- Once a virus crosses a critical threshold, it multiplies significantly faster. Rate of change in epidemics is anything but gradual.

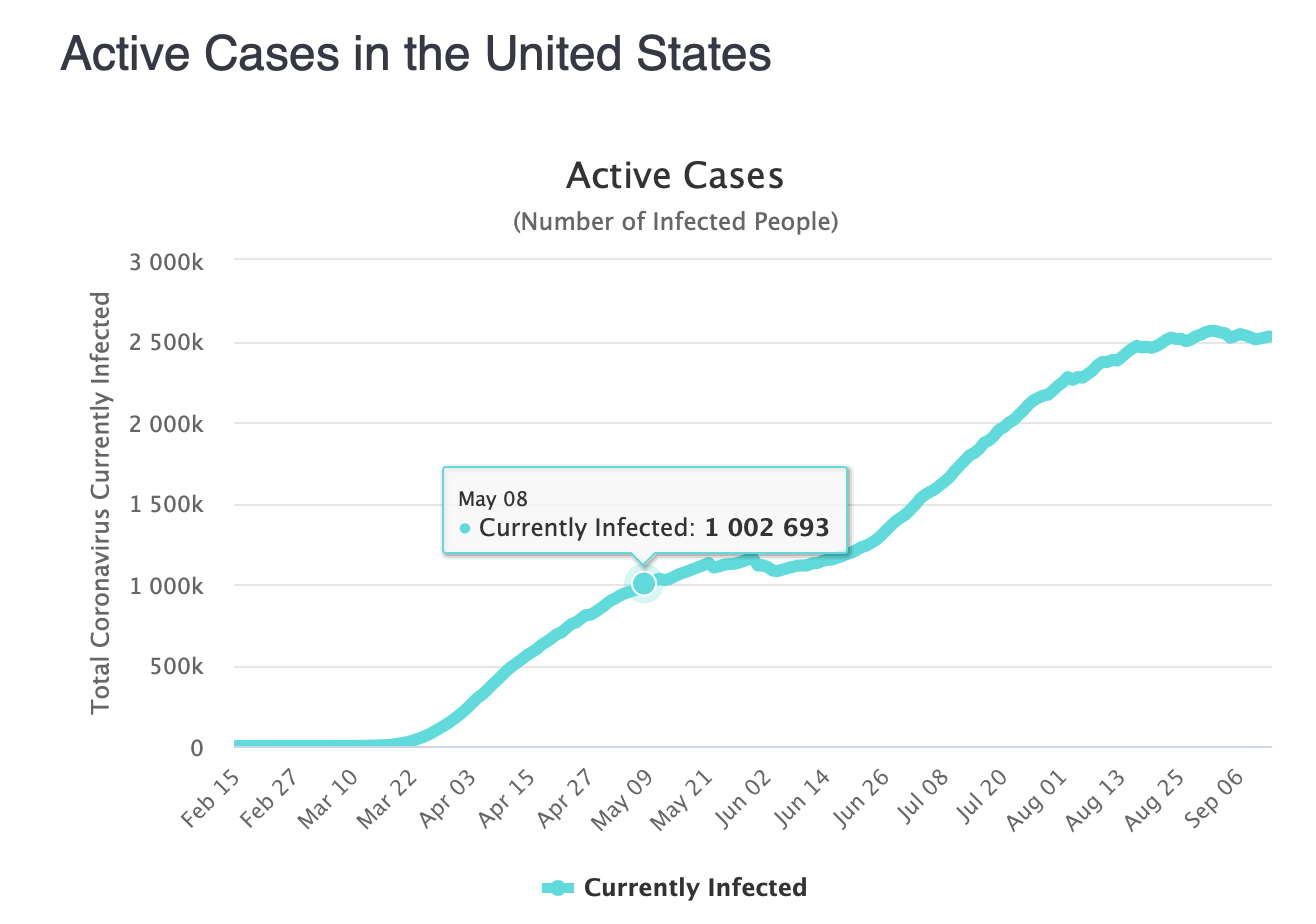

While the first two elements are pretty self-explanatory for viruses, let’s focus on the third element: Epidemics rise or fall in one dramatic moment. China first reported the existence of COVID-19 on January 7. It took less than two weeks for the United States to report its first case of the virus January 20. On March 11 – the day Adam Silver shut down the NBA – there were 1,248 active cases in the United States. It took less than two months for that number to climb above 1,000,000.

This sharp incline in cases is exactly what Gladwell was referring to. He gave it a specific name: The Tipping Point. It is, in his opinion, the most important characteristic when it comes to understanding the behavior of epidemics. For us to pinpoint how the scales get tipped in one direction or the other, we have to understand the conditions that allow for these sudden increases in change.

It gives us insight into a lot more than just viruses.

If we look at the newest trends, latest fads, how certain products blow up, or why specific ideas take off, all of these things follow the same exact rules that caused COVID-19 to spread into a global phenomenon. Epidemics don’t just explain how viruses spread. They explain how everything spreads. It doesn’t matter if it’s a life-threatening disease, social media app, or new household utility – there is an element that makes it contagious, it spreads from a small following, and it crosses a critical threshold – the tipping point – which causes its popularity to explode.

In fact, we’ve already discussed a great example.

I made no mistake when I referenced Silver’s decision as “the tipping point that sent everything over the edge.” When he shut down the NBA down indefinitely after learning of Gobert’s positive case, it took less than 24 hours for all professional and amateur sports in North America to be completely shut down. If epidemics can rise or fall in one dramatic moment, Silver’s decision was the dramatic moment that empowered leaders all throughout sports to take a backseat to greater social issues. If cancelling sports was the “new trend,” Silver was the trendsetter.

He’s just the kind of person we need to dive into if we want to understand the power of tipping points.

Remember how we talked about how little causes have big effects? Epidemics don’t start with a large following. They develop a large following because of a small and specific group of people. They prefer to keep it this way, too. Instead of following the trends and the logic of the majority, they blaze their own path and lead the wave of change from the front. You’ll see them sporting new brands, testing out new theories, rejecting tradition in the face of new evidence, and making decisions many would not have the courage to do. Some of it’s by necessity, some of it’s by curiosity, and some of it’s because they really don’t give a shit. They’re going to do something when it’s the least popular and end up becoming the mechanism that makes it popular. If we want to understand tipping points, we need to understand these men and women and how their decisions have ripple effects throughout society.

People like Adam Silver aren’t just important – they’re necessary. If we want to understand the conditions for change, we can’t just look at the message. We have to understand the messenger.

Only then can we start to understand how trends start, ideas spread, and how one eight minute video became the vessel that empowered baseball to finally “say no” to something that had been taught for years.

It was 2012 and Athletics prospect Josh Donaldson had hit rock bottom. Ever since his big league debut in 2010, Donaldson was having trouble solidifying himself as an everyday big league player. In 51 games at AAA San Francisco, Donaldson showed flashes of potential collecting 13 homers, driving in 45 runs, and slashing .335/.402/.598. At the big league level, Donaldson struggled batting just .250, accumulated an OPS of .687, and punched out 61 times in 75 games.

He was becoming, in his words, an infamous “Four-A” Player – the unspoken level in baseball reserved for players good enough to get to the show but not good enough to stay there.

Donaldson knew Four-A players didn’t last long in the game, but he also knew he wasn’t a Four-A type of player. In need of answers, Donaldson doubled down and started searching for them by going to the tapes. He had never been much of a self-evaluator and didn’t really care to watch any of his at-bats if they weren’t bombs (not necessarily a bad thing), but at this point he knew his bad swings were largely outweighing his good ones. To get a reference point for what it should look like, he decided to study up on three of the best hitters in the game: Jose Bautista, Allen Craig, and Miguel Cabrera. He dissected every move, looked at the differences between his swings and theirs, and began to incorporate some of what he saw into his. Sure enough, he started to see some results. In his final 51 games with Oakland in 2012, Donaldson batted .286 and accumulated an OPS of .822. These changes continued into the offseason with some help from private hitting consultant Bobby Tewksbary.

When Donaldson entered the box in 2013, he looked like a completely different hitter. What was interesting about these changes is when most players get off track they need to simplify their moves to have success. For Donaldson, he needed the opposite. He needed bigger moves to sync up his high octane swing. Big moves sure matched Donaldson’s big personality – he just hoped they would fuel some big-time results.

His career depended on it.

If we look at the changes, one of the most notable ones was the adoption of Jose Bautista’s signature leg kick. Considering the complexities of hitting a 95 mph fastball, most hitters tend to use smaller timing mechanisms so they can simplify their swing and increase their chances for hard contact. After watching film of the Dominican slugger and experimenting with his own version of it, Donaldson decided it was worth trying out in games. When you’re becoming a Four-A player, the barrier to entry for these kinds of adjustments is pretty low. Considering Donaldson’s trend-setting type personality, the barrier to entry happened to be really low.

Another big adjustment that Donaldson made happened to run contrary to what had been largely taught in baseball over the past several decades. Instead of taking the barrel directly to the ball in a chopping motion, Donaldson created a different action where he turned his barrel back towards the catcher. This “rearward barrel movement” was designed to help Donaldson strike the ball with his barrel traveling on a slightly uphill plane. If Donaldson’s goal was to hit balls hard and in the air, he couldn’t have his barrel traveling down into impact in a chopping motion. He had to do just the opposite. His barrel had to go back in order for it to go forward.

In the spirit of what we know about epidemics, this small sample size of experimentation ended up yielded big time results.

In 2013, Donaldson didn’t play a single game at the minor league level. Gone were the days of constantly bouncing between Oakland and San Francisco. He solidified himself as the everyday starting third baseman for the Athletics and slugged 24 homers, drove in 93 runs, and slashed .310/.384/.499. He went from becoming a Four-A player to finishing fourth in the MVP voting.

He wasn’t done yet, either.

In ’14, Donaldson continued on his war path slugging 29 homers, driving in 98 runs, and making his first career All-Star appearance. After being traded to Toronto at the conclusion of the season, Donaldson took his go big or go home personality to a completely different level. He exploded in his first season with the Jays anchoring one of the best offenses in franchise history that lead the MLB in runs per game (5.50), doubles (308), homers (232), RBI (852), and OPS (.797). Donaldson set career-highs belting 42 homers, driving in 123 runs, and winning his first-ever American League Most Valuable Player award. In three short years, Donaldson had gone from a fringe big leaguer into one of the most exciting players in the game and now had a platform where he could share his unique story to others who were at rock bottom the way he was back in 2012.

Little did he know the ripple effect it would have throughout the baseball community.

In August of 2016, Donaldson joined Mark DeRosa of the MLB Network in Studio 42 to break down his swing transformation that turned him from a fringe big leaguer into an MVP. Throughout the eight minute video, Donaldson shared his thought process at the plate and some of the things that were really important to him as a hitter. He discussed the rhythm and pre-pitch movement he added so he could get into his natural flow and sync up to the pitcher. He talked about how it was important for him to control his forward move using his rear hip as opposed to his back knee so he could maintain balance using his Bautista inspired leg kick.

While all this was going on, Donaldson emphasized how he wanted to stay as loose as possible so he could avoid adding any unnecessary tension in his swing. He wanted to create tension – but he didn’t want to create any before his front foot came back down to earth. The timing of it was just as important as creating any at all. For him, he created this tension by turning his body into a giant rubber band. If his lower half was the hand holding the rubber band, his upper half was the other hand pulling it back. He didn’t want to pull it back just a little. He wanted to pull it back as far as his body would allow without sacrificing his performance in the box.

When he started to talk about shoulder angles, DeRosa stopped Donaldson – recognizing he’s getting pretty deep into the swing – and asked him what he could give a 10 year old kid to go home with. After all, complexity is only as good as our ability to create simplicity. Donaldson’s advice was about as simple as it could get.

“If you’re 10 years old and your coach says get on top of the ball,” said Donaldson, “tell him no. Because in the big leagues these things that they call ground balls are outs.”

Simple, but powerful – and not wrong. In 2016, MLB hitters batted .239 and slugged .258 on ground balls. On fly balls and line drives combined, they batted .411 and slugged .785. Ever since Statcast started collecting data in 2015 (thanks for crunching some data, Randy), balls hit at 100 mph and at a 28 degree launch angle have a .705 batting average, go for extra base hits 70 percent of the time, and leave the yard half the time. Balls hit at the same speed but at a 5 degree launch angle (ground balls are considered anything 5 degrees or lower) turn into extra base hits just six percent of the time. Hitting baseballs at 100 mph will get you hits, but hitting balls at 100 and at the right trajectory helps you do damage. Teams pay guys who can do damage.

“If you’re 10 years old and your coach says get on top of the ball, tell him no. Because in the big leagues these things that they call ground balls are outs.” – Josh Donaldson, 2015 AL MVP

If you don’t hit the ball 100, hitting the ball in the air might actually become even more important. According to Statcast, balls hit at 75 mph but at a 5 degree launch angle have a .324 batting average and only 1 percent of those hits go for extra bases. If you hit a ball 75 mph but at a 20 degree launch angle your batting average jumps to .978 – a .654 increase. Hitting the ball in the air isn’t some scientific discovery that we recently uncovered. We’ve known this stuff works for a long time. If anything, it’s common sense.

To think about this, let’s do some math. The average baseball field infield is about 27,000 square feet. Out of the nine fielders on the field at any given time, six of them are within the perimeter of the infield. If we break down roughly how much each player would be responsible for if they shared the infield evenly, each infielder would need to cover 4,500 square feet. If we take the catcher and the pitcher out of the equation, each fielder becomes responsible for 6,750 feet.

Now let’s go to the outfield. The average outfield is about 77,000 square feet. Three fielders must cover this area. As a result, each fielder becomes responsible for 25,666.7 square feet – over 18,000 more square footage than what each infielder needs to cover. If you want to increase your chances to get a base hit, you want to put pressure on fielders that have to cover an additional 134’ x 134’ box of green. To put this into perspective, check out this video where Byron Buxton covers 84 feet to make a sensational catch in center field. Now imagine making him responsible for 50 more feet on that same play.

If you want to put pressure on the defense to make these kinds of plays, you’re not going to do it making contact with the top half of the baseball. After all, the pitcher is standing on a 10” mound and throwing to a catcher that is in a crouch. The baseball is traveling on a downhill plane. Swinging down on an object traveling down is a great recipe for killing gophers and elevator homers – not line drives.

This was the point Donaldson was trying to get across.

If we know hitting the ball in the air works, it would therefore make sense to design a swing that would help you drive ball in the air. Donaldson’s swing changes were designed to help him do exactly this. His problem was the swing he had learned his entire life was not helping him do this. He also knew he wasn’t alone.

Donaldson’s eight minutes in Studio 42 was his opportunity to share to the world the information he wished he had as a player a long time ago. It wasn’t just informative – it was empowering. Every player and kid in American now had the ability to tell their coaches to piss off when they told them to swing down, get on top of the ball, or keep it on the ground. Their bad swing wasn’t their fault. Instead, it was the fault of hitting coaches who had been feeding them bad information for years.

It was the perfect storm for an epidemic-like response.

Let’s go back to epidemics.

In order for a virus or trend to spread there must be some element of contagiousness. It’s a necessity for survival. If a virus can’t spread to a host body, it has no way to survive on its own. If an idea can’t stick and spread to a larger audience, it’ll be forgotten as soon as it was discovered.

While viruses are contagious by nature, ideas are a little bit different. They all have the potential to stick and spread, but there has to be something about it that makes it stand out – especially considering the amount of information that we’re forced to sift through on a daily basis. It might be easier than it’s ever been to spread ideas, but you could argue it’s harder than it’s ever been to make ideas stick. There’s so much information out there today that just sharing it isn’t enough. What’s shared needs to be remembered.

It’s a lot easier to remember it when it’s coming from one of the best hitters in baseball.

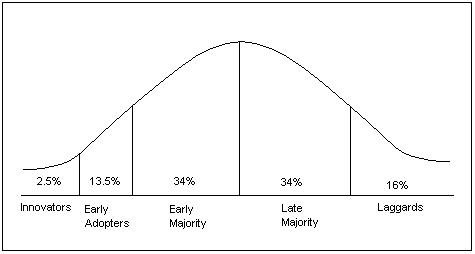

If we want to understand the role contagiousness plays when it comes to the spread of new ideas, we have to go to the second rule of epidemics: Little causes have big effects. When people are presented with new information, there is a pattern in how that information is received and adopted over the course of time. This is illustrated in the Law of Diffusion:

Notice how at the beginning of the curve you find the innovators (2.5 percent) and the early adopters (13.5 percent). These two groups represent just 16 percent of the population but are arguably the most important part of the population when it comes to influencing change. These are the kinds of people that are willing to grapple with the unknown, test out theories before they’re popular, and speak out about things that many might disagree with initially. What these people say and do have massive ripple effects throughout society because they introduce us to things we don’t know, challenge the things we do know, and force us to see things through a different lens.

It’s where you’ll find the Adam Silvers and Josh Donaldsons of the world.

Donaldson might not have invented the approach to hit the ball in the air, but he was the perfect kind of person to go against the grain with his career at stake. He was willing to wear some arrows and try out a different approach to keep a jersey on his back. Big leg kicks and rearward barrel movement might not have been popular, but Donaldson ended up becoming the mechanism that made them popular. After all, when you have an MVP kind of season everything you do becomes popular. If there was a moment in time where Donaldson’s words would have had the greatest amount of impact, the summer of ’16 was a pretty good time.

Now let’s go back to contagiousness.

If we break down what made Donaldson’s message stick and why it spread as quickly as it did throughout the baseball community, three things stand out:

- Authority

Where we get information is just as important as the content of that information. For Donaldson, he had all the right ingredients. As an everyday big league player he had credibility right off the bat. For better or for worse, we have to remember that big league players represent such a small portion of the population. If you were to take every single player that’s stepped between the white lines on a big league field, you wouldn’t even be able to fill half of Yankee Stadium – 18,918 to be exact. When big leaguers speak, we listen.

Now Donaldson wasn’t just any big leaguer – he was one of the best players in the game. He had just come off an AL MVP season in which he exploded offensively setting career-highs in numerous categories and lead the Toronto blue Jays to their first postseason appearance in over two decades. What he was talking about was getting results. This gave him the perception of an authority figure in the game of baseball.

When you take a guy like Donaldson and put him in front of a microphone on one of baseball’s most watched television networks, people are going to listen. If what he was doing was getting results at the highest level of the game, it’s worth listening to. You don’t become the 1 percent of the 1 percent by accident.

The messenger is just as important as the message itself. In the summer of ’16, Donaldson happened to be the perfect messenger to share his “new school” approach to hitting.

- Utility

Products and ideas take off because they present a solution to a problem people are facing. Donaldson’s message was no different. If your coaches had been preaching the importance of getting on top of the baseball and you haven’t had success in games, you now had a plausible theory on what’s been creating your offensive struggles. If Donaldson had transformed himself from a Four A player into an MVP candidate, you now had a chance to pull yourself from the bottom of the lineup and start contributing at a higher level offensively.

Creating utility is all about offering a solution to a problem people are facing. Donaldson’s thoughts might not have been popular to the majority, but he had proof of results and he was able to connect to a lot of kids who were facing the same issues he once did. After all, most of what he talked about just made sense. If the objective is to get the ball out of the infield, why would we try to get on top of the ball?

- Novelty

This one is interesting. Donaldson’s thoughts on trying to design a swing to do damage in the air were not new. Hall of Fame hitter Ted Williams was talking about this over forty years ago when he wrote his book The Science of Hitting. What made Donaldson’s message “new” was the public’s perception of it. You have to remember that the climate in player development over the past several decades had not been favorable to the idea of swinging up. For the large majority, it was very much the opposite. Hearing one of the best players in baseball basically shit on what most hitting coaches had been talking about for a long time was kind of a culture shock. Donaldson’s message was not new, but the way in which he presented it made it seem fresh, new, and attractive.

If you want to find a way to get the 84 percent on board, you’ve got to present your message in a way that makes it appealing. Making it seem new – even if it isn’t really new – is a great way to accomplish this. If the information you’re trying to share is novel, useful, and it’s coming from an authority figure, it’s going to spread just like a virus.

Donaldson’s interview just happened to be the tipping point that sent everything over the edge.

With this, there’s just one detail that we haven’t highlighted to this point: Epidemics can rise in one dramatic moment, but they can also fall in one dramatic moment. Trends are called trends for a reason – when something loses its novelty, utility, or authority, it becomes hard to keep it around. The 16% leading the pack have already moved on to something else. It might be cool to swing like Donaldson one year, but is it still cool to swing like Donaldson when he’s not an MVP candidate and he’s getting outpaced by guys like Cody Bellinger, Christian Yelich, and Aaron Judge?

Everything in this world must operate within a golden median. That median lies between two polar opposites that become the edges in which we have the capacity to operate. More times than not, we have to operate at those boundaries for some period of time in order to eventually bring ourself back to middle. Hot needs cold, high needs low, what’s good needs what’s bad, and what’s enjoyable needs what’s unpleasant. Baseball is no different. Stay back needs go forward, go fast needs go slow, and too much needs too little. Thoughts, cues, instruction, and interpretation all operate on some part of a spectrum between polar opposites. Our goal is to wind up somewhere in the middle, but sometimes we need to operate on one side of the spectrum or the other to find balance. Last week we might have needed to go fast – this week we need to slow it down. It’s all dependent on where we are and what we need.

When Donaldson couldn’t solidify himself as an every day big leaguer, he didn’t need to think about getting on top of the baseball and keeping things simple. He needed the exact opposite to find balance on his spectrum of needs.

I just wonder if the scales have tipped too far in that direction.

Before we begin, let’s start on some common ground. All great hitters make contact with the ball when their barrel is traveling slightly uphill. It’s not complicated – it’s really common sense. We know the pitch is traveling on a downward trajectory of about 6-10 degrees. We know line drives are the most valuable batted ball in baseball. Line drives happen in the air. If the goal is to maximize your ability to hit line drives, the barrel cannot be traveling down into contact – it must match the plane of the pitch and travel slightly up. As mentioned above, this stuff is not new. In many ways, we’re just catching up to what a lot of the best hitters knew a long time ago.

However, just knowing all good hitters swing up is not enough. How they swing up is equally as important.

The north to south barrel that’s synonymous with the “new school” swing up approach might be the attractive thing to do as of late, but it’s not necessarily what a lot of the greatest hitters have done. Vicious upper cuts might be trendy but they’re not the only way to hit a baseball in the air. In fact, some of the best hitters this game has ever seen had anything but a vicious uppercut. Their path was very flat. They didn’t have any issues hitting the ball in the air, either.

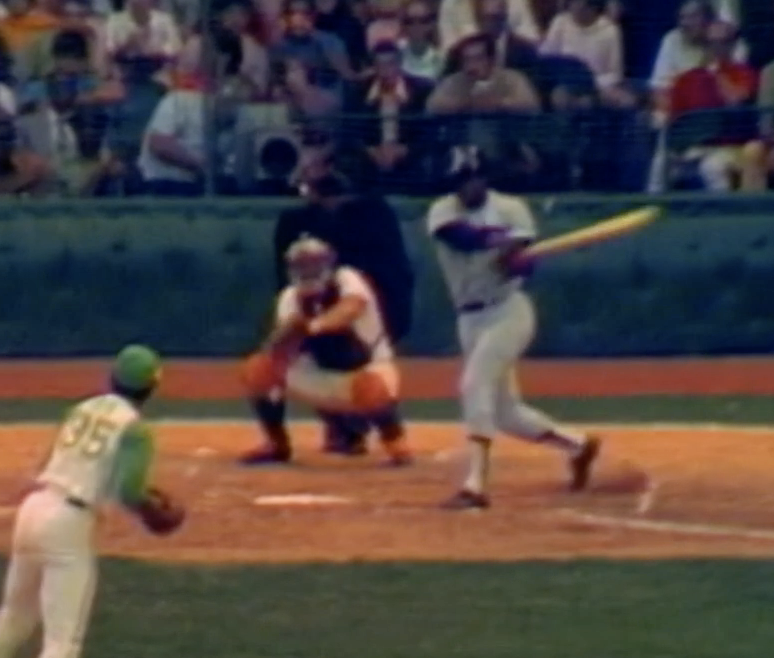

To get a feel for this, below is Hank Aaron – arguably the greatest hitter of all time – hitting a homerun. Pay close attention to how his barrel moves through space.

Notice how flat his barrel is when it comes through the zone? He doesn’t have a big Bellinger-like upper cut where his barrel starts in the southern hemisphere and exists in the north. If anything, it just works east to west around the equator. He uses his hands and wrists to manipulate the barrel into contact. After contact, the barrel never rises above the letters on his jersey and finishes below his opposite shoulder.

It doesn’t really look like a swing path that was designed to hit 700 home runs, but that’s because our perception of the optimal swing is relative to what we’ve been seeing recently. With the recent push to drive balls in the air more often, we’ve seen a lot more golf influenced swings where the barrel is working predominately in the north to south plane of rotation. It’s great for some hitters – J.D. Martinez and Freddie Freeman being two examples – but it’s not optimal for everyone. Hank Aaron didn’t a big uppercut to the ball to do damage in the air. He needed to be flat – and he’s not alone.

Let’s check out another Hall of Fame hitter: Jimmie Foxx. Foxx finished with a lifetime batting average of .325 over 20 seasons in the big leagues belting 534 homers and accumulating a lifetime 1.038 OPS – good for fifth all time. This is what his swing looked like:

Very similar to Aaron’s. Manipulates the barrel with his hands and wrists, bat works east to west around his torso, and finishes his swing with the bat below his opposite shoulder. I really like this angle of Foxx because while his swing is pretty flat, his barrel still makes contact with the ball traveling slightly up. Just because you have a flat swing does not mean you can’t strike the ball with your barrel traveling slightly up into contact. Guys like Foxx and Aaron didn’t need to work north to south to do damage in the air. They needed to be flat.

How about another Hall of Famer: Mike Schmidt. Throughout his 18 year career, Schmidt rewrote the Philadelphia Phillies record books setting franchise records in WAR (106.9), total bases (4404), home runs (548), and runs batted in (1595). This is what his swing looked like:

Same thing. Flat bat path, hands and wrists manipulate the barrel, and the bat finishes underneath the opposite shoulder. Zero issues elevating the baseball. It’s almost as if we’ve written off these kinds of swings and buried them deep in the history books in favor of the modern “launch angle” swing. However, we never really buried them.

We just stopped looking for them.

There are plenty of examples of guys that play today who have had a ton of success using an east to west approach with their bat. It just seems like they’re north to south because of the angle of their trunk.

One of these guys is Mike Trout.

When we look at how the bat moves through space we want to see the barrel turn in tangent with the middle as we start to rotate. How it turns is just as important. In order to make efficient moves to the ball, we need the barrel to work around the trunk on a geodesic path – meaning straight but on a curve. This helps the barrel capture energy using the path of least resistance so it can maximize force transmission while maintaining space and direction. These three elements are critical for high level hitters. If the barrel does not work around the trunk using the most efficient path possible, it becomes a lot more difficult to check these three boxes.

A great comparison for this is the arm. How the arm works around the trunk to deliver the baseball is very similar to how the barrel needs to work around the trunk to strike the ball. Whether it’s a bat or a ball, we need to work around the trunk and get across our body so we can produce force. The angle of our trunk then becomes a key element in understanding the path of the bat or ball. If we know arm slot is determined by the amount of trunk tilt pitchers create into foot plant, bat path becomes influenced by the amount of posture we create throughout the swing. When hitters create more posture and their trunk works closer to parallel with the ground, it creates the illusion of a north to south path when it’s really east to west with trunk tilt. This is exactly what we see with Trout.

The best way to explain this is to show it visually. If we normalize for trunk tilt, this is what Mike Trout’s swing looks like.

Looks a little more flat now, doesn’t it?

Trout’s swing might look north to south because of the amount of trunk tilt he creates, but it’s more of an east to west swing – just like Aaron, Foxx, and Schmidt. While we’ve discussed a lot of old school hitters to this point, flat swings are not just an old school thing. They’re a new school thing too. Jose Altuve, Giancarlo Stanton, and Christian Yelich all have flat swings – it just gets a lot easier to see it when we get take trunk tilt out of the picture.

How you swing up is just as important as knowing you need to swing up.

So now let’s go back to Donaldson’s thoughts. Deliberately trying to elevate the ball can create some positive adaptations for some, but it can also make others look like this:

Trying to swing like Donaldson is cool until it puts you in a really bad position at landing with excessive counter rotation of the torso, the bat has a really long arc to the ball, and there is zero ability to transmit force with direction because deceleration patterns are non existent. There’s a reason why big leaguers don’t exhibit bat speeds north of 80 mph. They do not swing like this.

However, the problem is this is what some kids thought they needed to do after they watched Donaldson’s MLB Network segment. This kind of disconnect causes trends to lose their zest. When we jump on what’s new and lose sight of what matters, messages become misinterpreted and ideas get taken to the extremes. Fads are aren’t meant to be factual. They’re fragile – and they should be handled accordingly. There were plenty of hitters who went all in on Donaldson’s ideas and ended up getting worse because they weren’t what they needed at that moment in time. What they needed was perspective (and maybe some decel patterns, too).

Everything that goes around eventually finds its rightful place of importance. Donaldson’s video got really popular really quick, but it didn’t quite hold its substance because the interpretation didn’t match the intent of the message. This creates a big problem. How we interpret information is just as important as the information itself. When the interpretation and the information don’t match, you’ve created the perfect storm for a kid to know enough to be dangerous and not enough to be effective.

Swinging up is a great idea until we drop our back shoulder too early, get stuck on our backside, fly open, and get peeled out of the ground before we ever get a chance to put force into it. Too many kids became so focused on keeping the ball off the ground because Donaldson told them to say no to ground balls. However, what they really needed was something of the opposite so they could get their swing back to a better place. After all, there are big leaguers who needed to intentionally hit the ball on the ground in batting practice so they could elevate it at 7 o’clock.

When the interpretation and the information don’t match, you’ve created the perfect storm for a kid to know enough to be dangerous and not enough to be effective.

If we want to be effective, we have to see how everything fits on the entire spectrum. Just jumping on the newest and latest stuff might get you some immediate returns, but it can also send you pretty far off the deep end if you don’t see things for what they really are. The whole swing up wave and the north to south barrel has helped a lot of players, but it’s also hurt plenty more. Coaching isn’t just knowing all players swing up – it’s knowing when some guys need to think down so they can swing up. How we swing up is just as important as knowing everyone needs to swing up.

So where do we go from here? Well, that’s the fun part. We know the north to south barrel works and we know the east to west barrel works. We can’t just look at path by itself to determine what’s optimal for someone. We need to see how the path matches up with what’s going on with the rest of the body. Similar to pitching, we’re trying to get the planes of rotation to match. If the arm is working in one direction and the pelvis and trunk are working in another, you’ve got a problem.

Hitting is the same thing. If you’ve got a guy who’s working north to south with his barrel but east to west with his hips, you’ve created a mismatch that’s going to have a negative impact on performance. East to west hips are guys like Trout and Aaron – their belt buckle works around the equator as the hips rotate. North to south hips are guys like Freeman and Joey Votto – they get rotation by creating more of a hip extension move (similar to how you would deadlift). They’re also two guys who have had a ton of success with south to north barrels. When the hips and the path match, you’ve got a recipe for hitters to mash.

The key becomes understanding when they don’t match. If you have a hitter who’s constantly getting beat up in the zone or slicing balls to the opposite field, they might have a mismatch where their hips are working east to west and their barrel is working south to north. This is costing them a ton of space and the ability to transmit force out in front with direction because their hips are working one way and the barrel is working the other way. Flattening their swing out might be the medicine they need to get the planes to match up.

This also works the other way around. If you have a hitter who’s hitting elevator homers in BP and they’re using more of a hip extension pattern down below, getting them to think more north to south can get the two to match up (e.g. J.D. Martinez). East to west paths with south to north hips are just as bad as south to north barrels but east to west hips. It’s not about whether north or south is better than east to west. All we’re trying to do is match up the planes of rotation. It just so happens that a lot of guys have east to west hips. Giving them a north to south path will make them worse. Don’t get caught up just looking at how the barrel works through space. See the entire picture. Flat swings don’t work against your ability to hit the ball in the air. Mismatches do.

Real coaching isn’t about clinging to the latest fads and jumping on what’s fresh in the player development community. Coaching is seeing truth amidst the hype and understanding that everything will find its rightful place in time. Kids don’t need fads. They need mentors who can guide them through the information that we are constantly bombarded with on a daily basis. Sometimes this requires an uncomfortable conversation with a kid who took Donaldson’s message too seriously.

While we have yet to find a vaccine for COVID-19, our vaccine to guard us against the ugly side of information epidemics is the truth. Finding truth – just like any science experiment – starts with empirical observation. If we know that some of the best hitters this game has ever seen had east to west hips and east to west barrels, we can’t just tell kids they need to swing up and let them self-organize into good positions. They need good coaching. How you swing up is just as important as knowing you need to swing up.

Donaldson’s message might not have the same flavor that it did back in the summer of ’16, but we still haven’t quite found the other end of the spectrum as a baseball community. Everything in this game is cyclical. High heaters and breaking balls might be trendy now, but it’s only a matter of time until we see sliders and two seamers make a comeback. North to south barrels might be trendy now, but it’s only a matter of time before we start seeing more guys teach east to west swings. It all works, but not all of it works for everyone. Information may come and go but good coaches will never go out of style. Good coaches understand how you swing up is just as important as knowing you need to swing up.

It’s time we start finding our way back to the middle.