“It can be said that the ecological niche occupied by a species supplies the species with the energy it needs for its survival. In that case, the fittest can be defined as those members of a population that make the most economical use of the energy sources available in their ecological niche. It is our belief that energy efficiency is the absolute criterion for survival.”

– Serge Gracovetsky, from The Spinal Engine

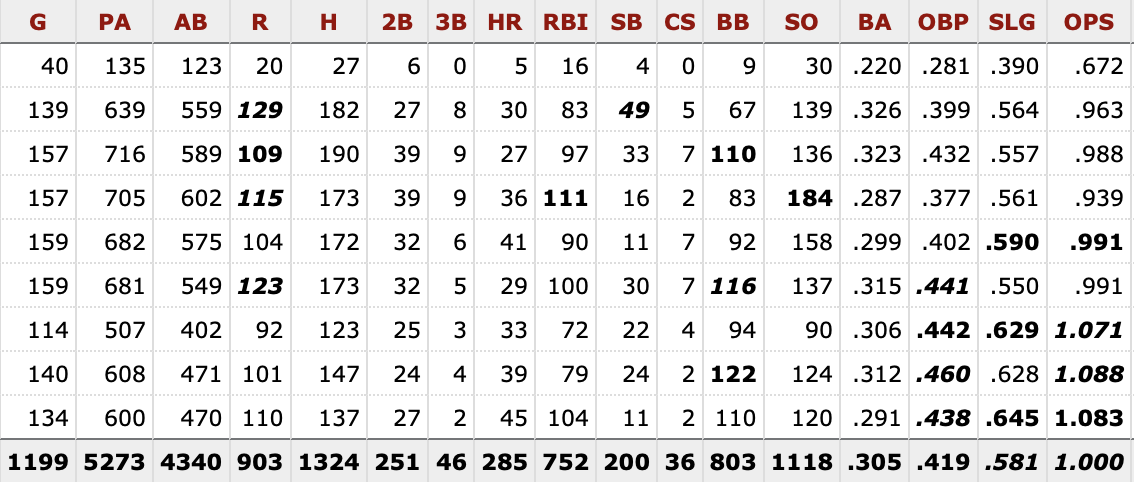

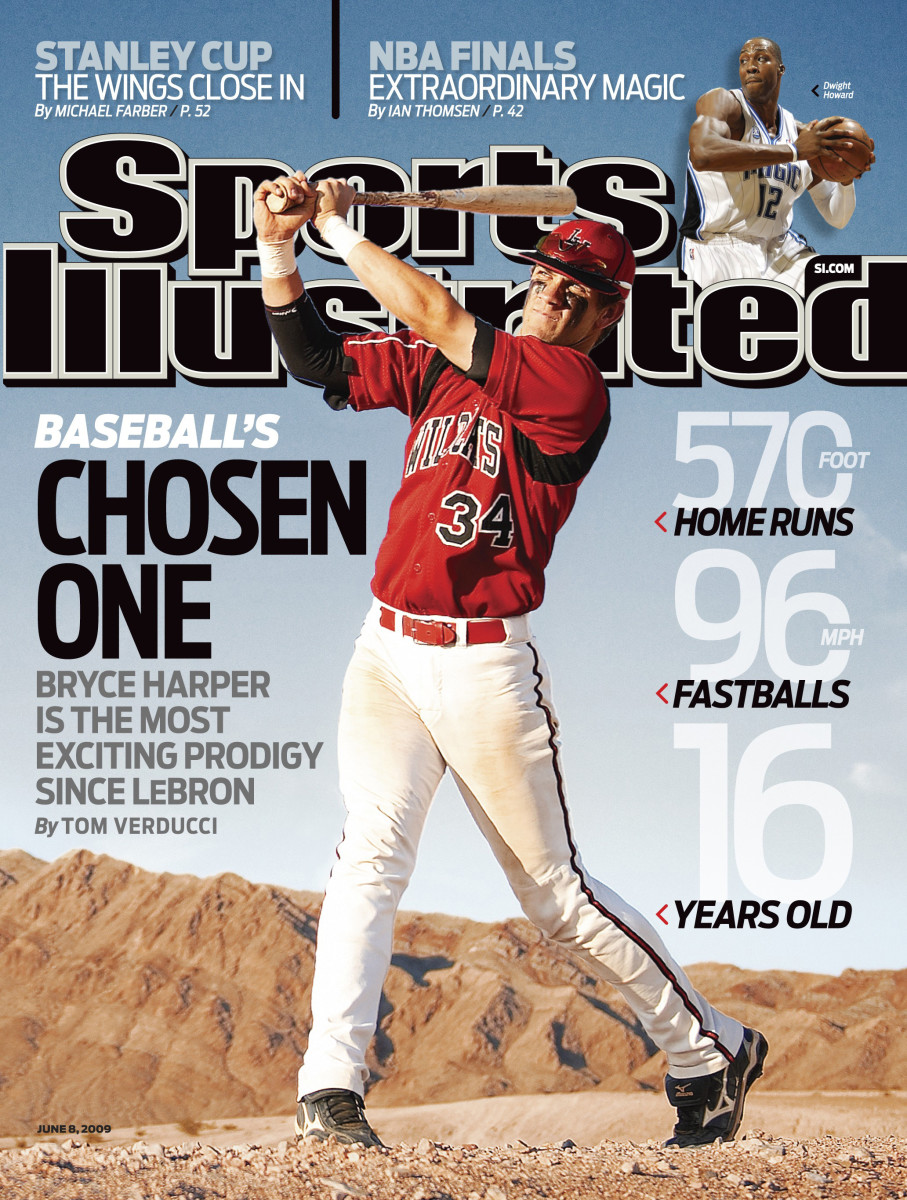

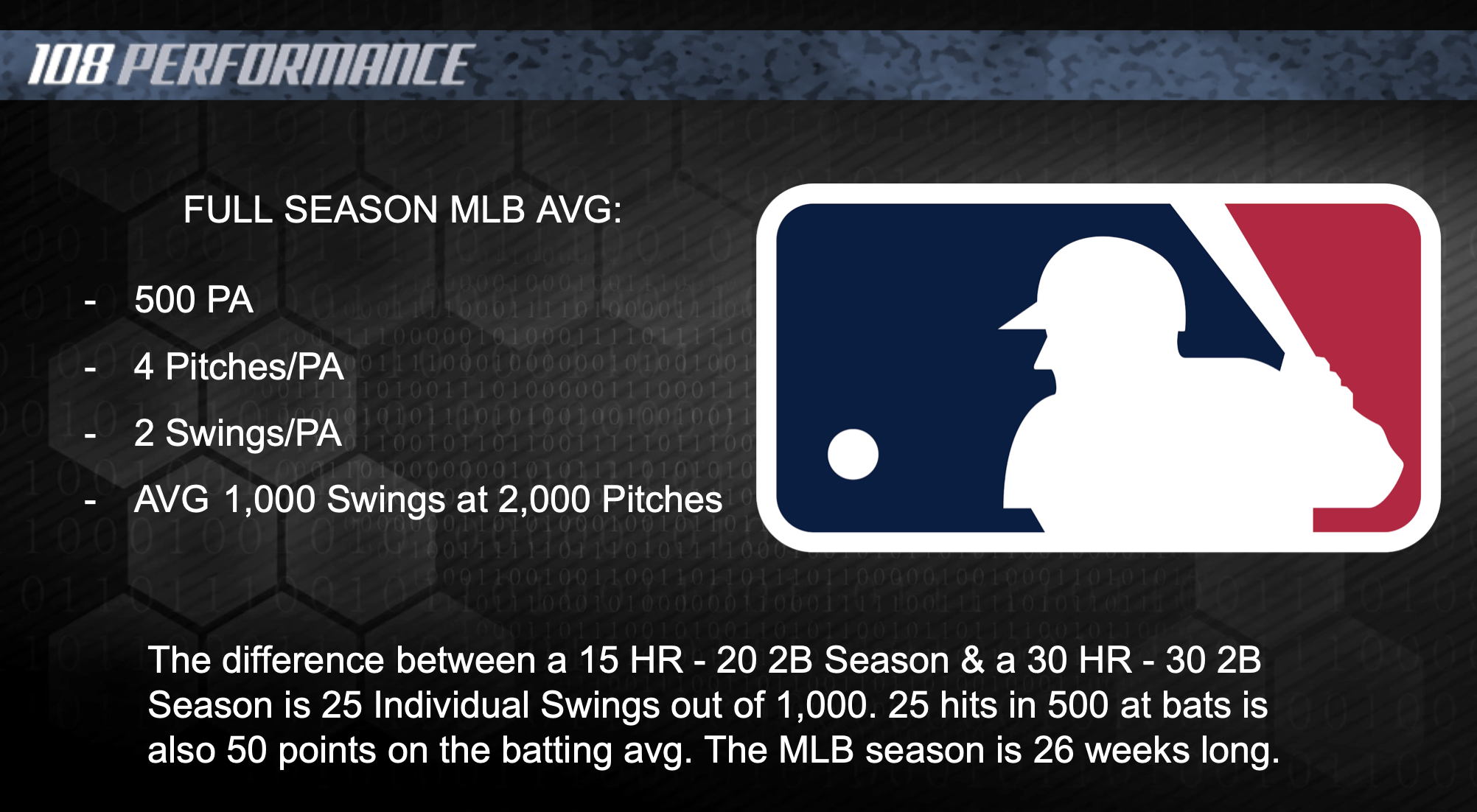

Before we get into the problems with Harper (see week nine), let’s start with the success of Trout. If we put it in its most simplest form, Mike Trout is really good because his moves are really efficient. In the words of Serge Gracovetsky, he accomplishes the most using the least; the hallmark of an efficient species. He’s able to consistently get to good positions so he can replicate his best swing under the constraint of the task more than anyone else. If 25 swings over the course of a season can be the difference between 15 homers 20 doubles and 30 homers 30 doubles, Trout doesn’t waste any of these swings.

As mentioned in the last article, Trout’s moves haven’t changed much at all since he first entered the league.

When we move to and through good positions, it’s much easier to replicate (or unlock) out best moves because we’re working from positions of stability. Stability gives us the ability to take a monstrous bandwidth of potential movement solutions (see Bernstein’s degrees of freedom problem) and narrow it down to the ones that makes the most sense for us. When we narrow this bandwidth, we increase our chances for our best moves to show up because there are less solutions to sift through. It’s just like the process of searching for a book in an online database: The more stability we have, the more letters we have at our disposal and the easier it is to find the title we’re looking for. This is efficiency: We take a database of thousands of books and narrow it down to the one we need. When we increase our chances of finding the right one, we decrease our chances of selecting the wrong one.

Another way to think about the error reduction process (i.e. efficiency) is to look at it through the context of building good habits: You want to make what is desirable as easy as possible and what is undesirable as difficult as possible. If you want to start eating better, place healthier snack options within sight and reach and hide the unhealthier options where they’re difficult to access. When we get into strong, stable positions, we make it easier to grab the apples and carrots and make it harder to revert to the cookies and chips. When we get into unstable positions we don’t build any barriers to entry; everything in the pantry is within sight and reach – and the stuff we should avoid always seems to catch our eye. There’s a reason why grocery stores make you walk all the way to the back of the store when all you needed was milk and bread.

Now this doesn’t mean we won’t find ourselves grabbing a few too many cookies every once in a while. Hitting a 95 mph fastball is not easy and really good hitters are going to make errors from time to time. However, these errors in elites happen far and few between when compared to their counterparts. Dan Pfaff of ALTIS explained how the best 100 meter sprinters don’t separate themselves in the first 50 meters; they separate themselves in the last 50 because they make the fewest errors.

We reduce errors by moving to and through stable positions consistently and efficiently. Mike Trout is no exception to this – and it’s a big reason why he’s had so much success. To figure out how Trout makes it so easy to stick to his “diet,” let’s break down some of the positions he gets to and how he moves through them to create robust, efficient movement patterns.

Forward Move

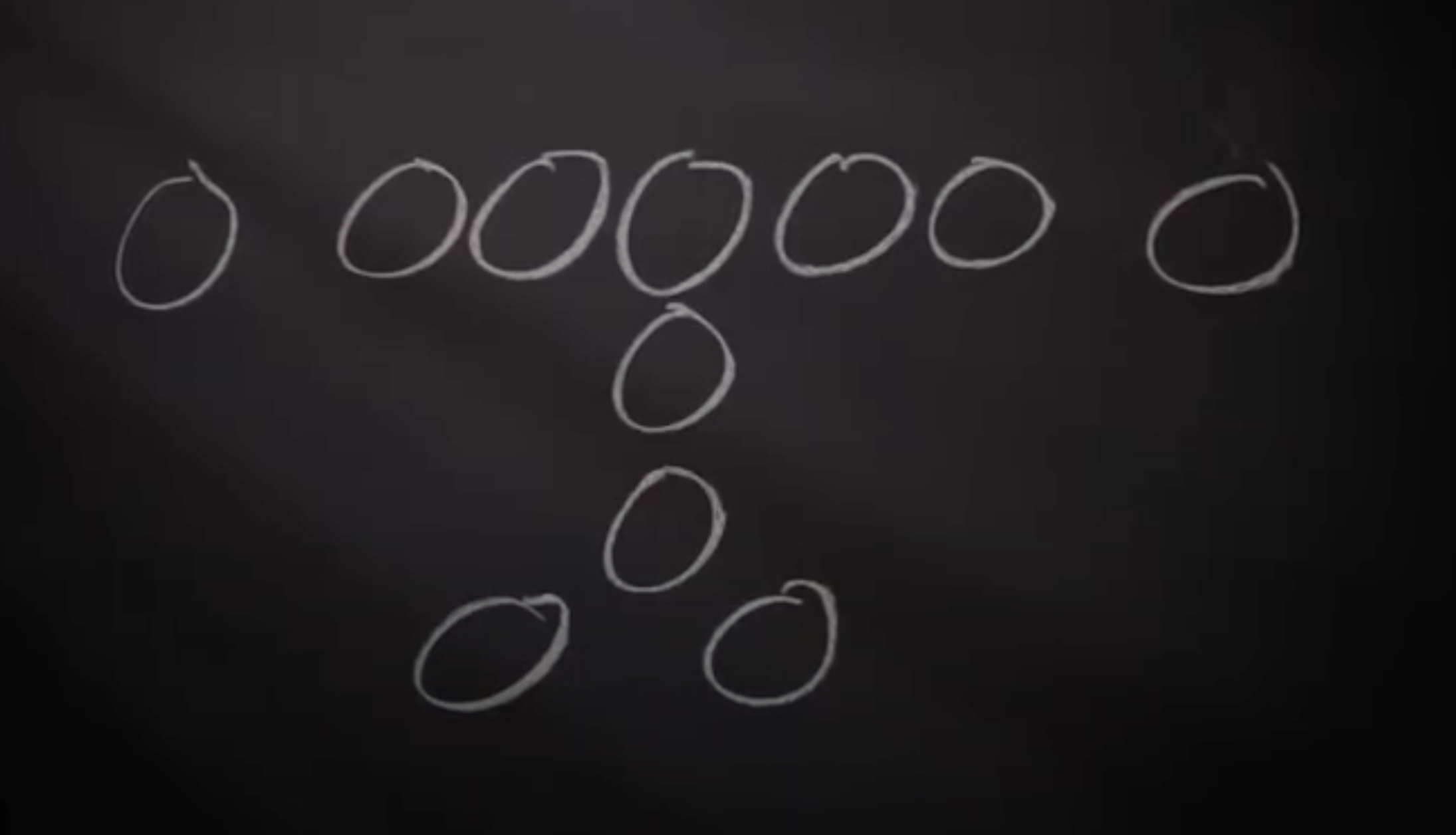

The forward move in hitting is when the hitter makes a move out of balance with their lead leg and begins to translate their center of mass forward. If we look at Trout, we notice his:

- Head stays over belly button, trunk stays stacked over pelvis

- Front shoulder stays down, works into the ground

- Chest works over the plate

- Center of mass gains ground towards the pitcher

- Feet spread apart

- Back knee points works towards catcher, back hip externally rotates (ER)

A good forward move in hitting is just like an infield pre-pitch hop: It’s an anticipatory move that helps us gather information about the incoming pitch so we can make good decisions. In order to navigate the chaos of a big league arsenal, we need to operate from stable positions that help us maintain balance, direction, and posture. If we look at Trout, we notice he’s able to create stability for his pelvis by sinking into the ground, spreading his feet apart, hinging, and pulling on the fascial slings that activate the co-contractions of muscles around his pelvis. In doing this, he’s able to use the ground as an amplifier for ground reaction forces – not compensatory patterns.

In order to use the ground effectively, we need to be able to put force into it – but how we put force into it is just as important. If we look at Trout, notice how he’s able to hinge and get his chest over the plate. How our torso works in relationship to the ground plays a huge role in how we put energy into it. To think about this, consider what you would look like if you were trying to drill a hole with an auger. For you to drill deeper, you need to get your chest over the drill so you can lay your weight into it. If we get stuck back behind our heels we lose this position of leverage (remember this one for later).

When we get to a good position of leverage at landing, we give ourselves the ability to get to our front side so we can stop our pelvis as we start to turn translation into rotation. If we want to rotate fast we need to stop fast; we can’t stop fast if our pelvis gets in the way. Getting to our front side clears space for us and gives us the ability to use the ground to our advantage as we start to rotate. It’s part of the reason why some guys need to think about swinging down; Trout and Harper actually being two of these guys. If we get stuck on our backside and our pelvis is in the way, we lose our ability to rotate powerfully and efficiently. Thinking about swinging down and getting to the front side can help give us the space we need to get our best moves off.

Another important thing about the forward move is that it is controlled; it is not a rush job to get the front foot down. Trout’s forward move doesn’t create a lot of noise – it’s simple, repeatable, and it helps him get to good positions so he can make good swing decisions. Something Eugene likes to talk about is the idea of pretending to “sit on a horse” with the forward move. We’re not going to rush down or violently slam into the ground if our goal is to straddle a horse at landing; we’re going to control our center of mass as it translates forward. This helps us land in a good position where we’re balanced and we can put force into the ground as we start to rotate.

Landing

Coaching off snapshots is a risky way to evaluate – but looking at where a hitter lands can give you a lot of information about the movement that happened before it and what will likely happen after it. If we get Trout to foot plant (also see gif above), we notice he:

- Lands in a position of balance with his head over his center of mass

- Anchors his pelvis into the ground by gripping it with both feet

- Hinges to create posture

- Keeps his trunk stacked over his pelvis, which stays closed

A great way to think of the landing position is to think about an analogy from Barry Bonds. When Bonds would hit, he would try think about landing in a position where he would be able to dodge a dodgeball. If you think about what this position looks like, you need to be able to stay centered, keep your weight distributed 50/50 between both legs, and get your chest over the ground in an athletic position. This is the same position you would be in if you were guarding someone in basketball, returning a serve in tennis, or getting ready to field a ground ball.

This is the same position Trout gets into – as well as many other high level hitters. It’s stable, it’s repeatable, and it gives the upper body the stability it needs to mobilize around it.

When we operate from a position of stability at landing we give ourselves the ability to make efficient moves to the ball – the next part of the swing we’ll take a look at.

Move the Middle & Decel

When the front foot lands, the ball has traveled more than two-thirds of the way towards home plate.

This creates a significant time constraint for the hitter – as if they weren’t under one already. Because of this, Trout needs to be incredibly efficient as he starts to accelerate his bat into the zone. For him to do this, he needs to:

- Stabilize and stop his pelvis

- Hold his line as he starts to rotate

- Make moves with his barrel as the middle starts to rotate

Let’s look at the first one. When Trout’s front foot lands notice how he stops the translation of his center of mass and begins to rotate around the center of his body. To get a feel for the axis he rotates around, visualize a line that starts at the base of the pelvis and works out through the top of his head.

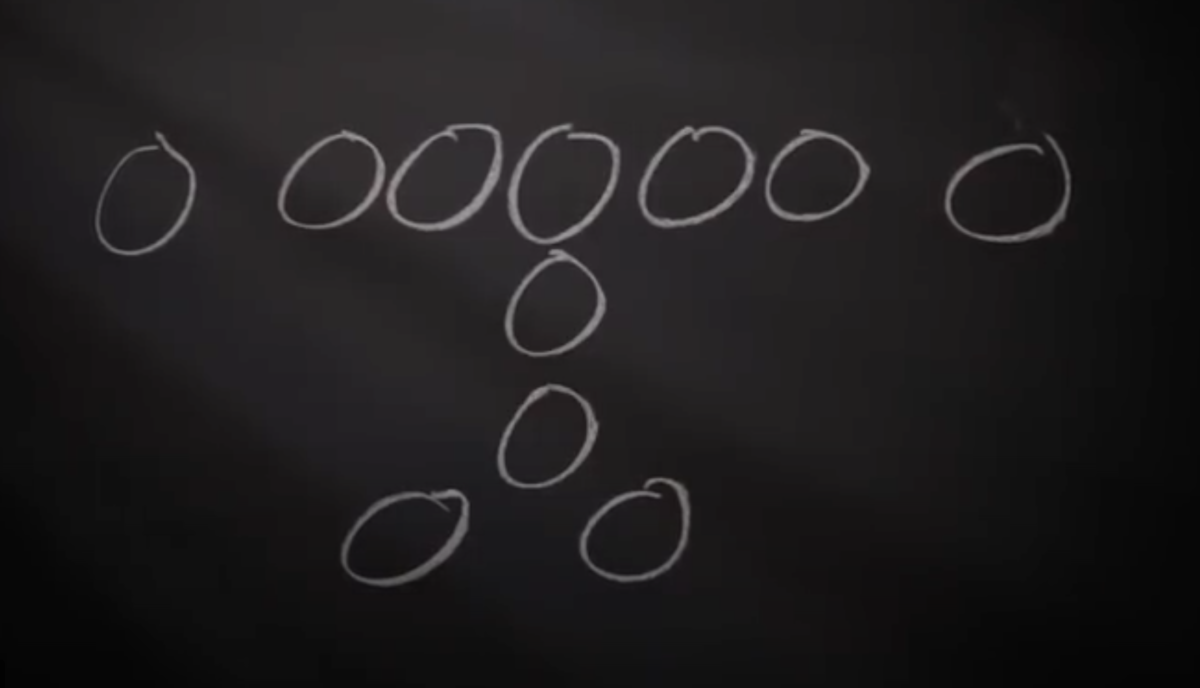

Elite athletes are really good at rotating around this line in a small window of time and space (i.e. rotating in a telephone booth).

For this to happen, Trout must be able to grab the ground, stabilize, and stop his pelvis. An inability to stop is going to create a huge energy leak that negatively impacts rotation and prevents hitters from compressing force into the ball.

To get a feel for what this stopping looks like, check out Trout’s belt buckle below.

See how it moves backwards towards the catcher after contact?

This tells us that Trout has stopped his pelvis so it can work as a slingshot for the torso to accelerate. When the torso has reached peak speed it follows the same pattern and stops so the arm can pick up speed and deliver the ball. This chain reaction of decelerating and accelerating segments is what creates the kinematic sequence. If the pelvis can’t stop the rest of the sequence falls apart because it doesn’t have a stable base to work from. You’re going to see this same exact move from a lot of the best hitters in the game – even this guy named Bryce Harper.

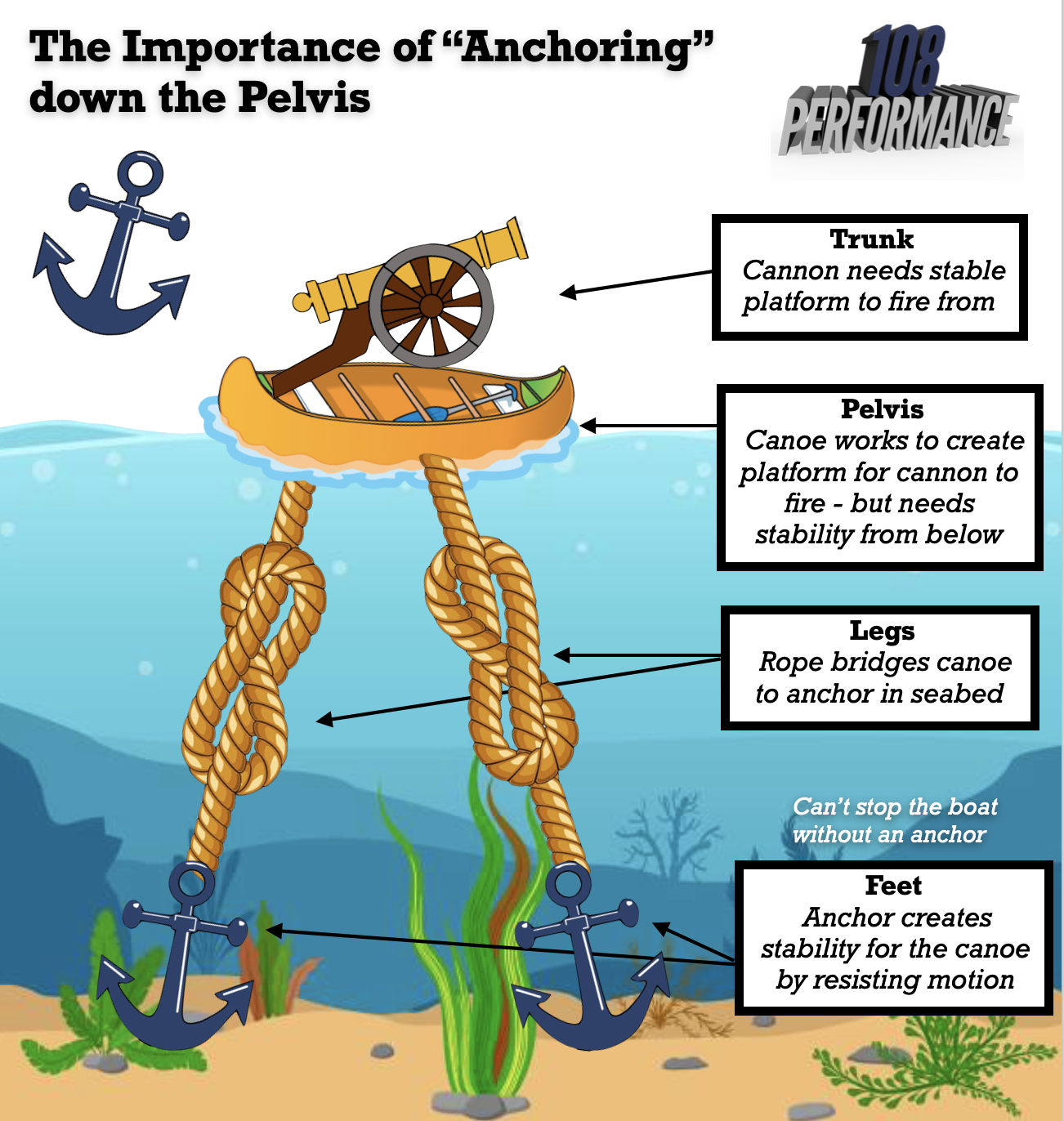

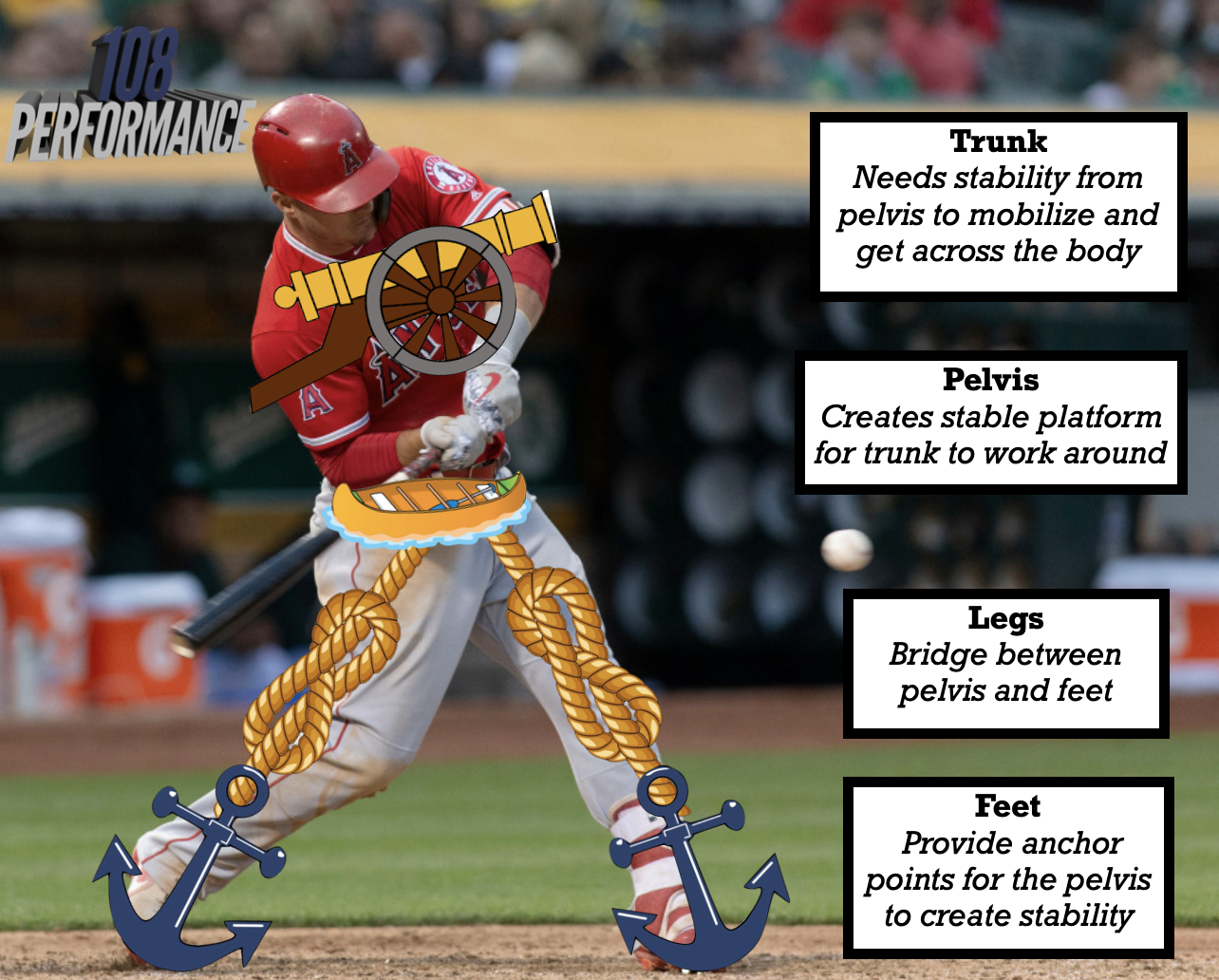

The pelvis can only stop and counter rotate if it’s working from a position of stability. Landing in an unstable position is like trying to throw on the brakes on a sheet of ice; it doesn’t usually end well. While we’ve already established Trout lands in a stable position, it’s even more important for him to hang on to this stability so he can maintain tension and intra-abdominal pressure through a ballistic movement like rotation. For him to maintain this stability, he’s going to need some anchor points to make sure he doesn’t go anywhere. It’s just like shooting a cannon from a canoe: You’re going to be in trouble if you don’t have that thing anchored in from both sides.

Trout’s lead leg and back leg work together as a force couple by creating anchor points for the pelvis and torso as they work reciprocally against one another (think about trying to rip the ground apart). In order to pull this off and maintain tension throughout the system, Trout uses a kick back move and anchors in the air the same way a PGA bowler would. This keeps his slack line tight and gives the system stability so it can stop and compress force into the ball.

When we can get to a stable position at landing and maintain this stability through rotation by stopping, we give ourselves the ability to hold our line. This “line” simply refers to Trout’s barrel path as it moves through the zone.

His ability to stop his pelvis is going to play a huge role in the path/line of his barrel because it keeps him from drifting after foot plant, peeling off towards the 3rd base dugout, and continuing is rotation after contact. He gives his barrel the ability to stay through the zone because because he gets into good positions and moves well through them – creating adjustability. If Trout drags his pelvis, his barrel is going to follow suit and get dragged along for the ride. When the barrel drags we create a disconnection from the middle that negatively impacts path, adjustability, and force transmission.

This leads in to the third part: Trout’s barrel maintains connection to his torso. When his torso starts to rotate, his barrel is going to start making moves to the ball. These two moves must be synchronized to maximize efficiency of the pattern. When hitters have lost connection, their torso has started to rotate but their barrel hasn’t. If the middle is moving and the barrel isn’t, your barrel is dragging.

This is not to be confused with the “separation” of the torso from the pelvis. The separation we’re looking for is a stretch reflex created by a decel pattern – not an active move where we prevent the hands from moving with the torso. Greg Rose of TPI has done research with some of the best golfers in the world and has found the best create just five degrees of separation after their back swing. Trying to actively create more is going to put you in a position where your hands get stuck and you create a disconnection from the middle. Separation isn’t about creating gaps – it’s about closing them as quickly as possible. We need connection in order to efficiently close these gaps.

The positions Trout gets to give him the framework he needs to get his best moves off; his efficiency helps him move to and through those positions optimally and consistently. If we want to understand what makes Trout really special, we can’t just look at these positions in isolation – we need to view them as interdependent parts of an entire system under the umbrellas of space, direction, and force transmission.

Trout gives himself space by anchoring his pelvis into the ground, hinging, getting his chest over the plate, keeping his torso stacked over his pelvis, and landing in a 50/50 position. He gives himself direction through the middle of the field because he’s able to get to his front side, stop his pelvis, and keep his barrel connected to his torso as he starts to rotate. He optimizes his window for force transmission because has space to stop his pelvis, rotate in a telephone booth, and maintain tension through the strike so he can compress force into the ball.

Trout’s impressive physical ability gives him the ability to punish balls – his efficiency gives him the ability to do it consistently.

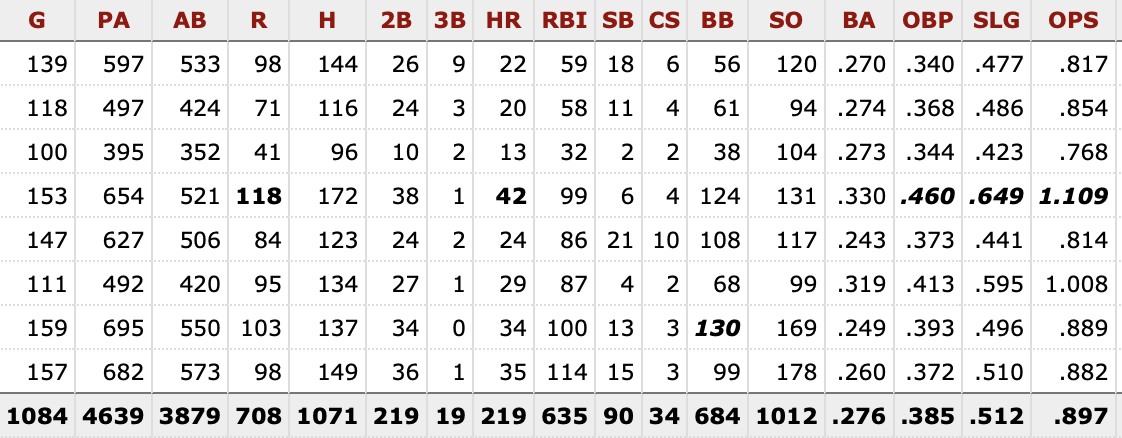

Now let’s go back to Harper.

How many of these boxes do you think he can check off consistently?