Thought for the Week: “Silent and listen share the same letters.” – Fred Corral, Missouri pitching coach

What does it mean to be symmetrical in an asymmetrical sport?

Building symmetrical baseball athletes is kind of a paradox when you think about it; we’re trying to build balance when our skill largely forces us to be out of balance. Throwing or hitting a baseball is an asymmetrical skill. Aside from the ambidextrous population, all players are going to have a dominant side from which they work out of for the entirety of their career. Every swing or throw is going to be done from one side of the plate or the rubber – we don’t really go to the other side and “balance” things out. However, this doesn’t mean that symmetry isn’t important. We want to build symmetry in baseball athletes – but before we can build it, we need to define it.

Our extracellular matrix (ECM) system plays a crucial role in human movement because it deals with the fascial system. Any conversation about how the body moves must start here because fascia is involved in it all. The easiest way to think about fascia is to think of it as a giant spiderweb that is strong as steel, flexible as thread, and is woven through all of our muscles, tendons, ligaments, and everything else inside of our body. It is the bridge that connects everything in our body into one integrated system. No movement in our system happens in isolation; everything is interconnected through fascia. To talk about muscles and bones without talking about fascia would be like eating a Klondike bar without the shell – we’re ignoring the very thing that’s holding it all together.

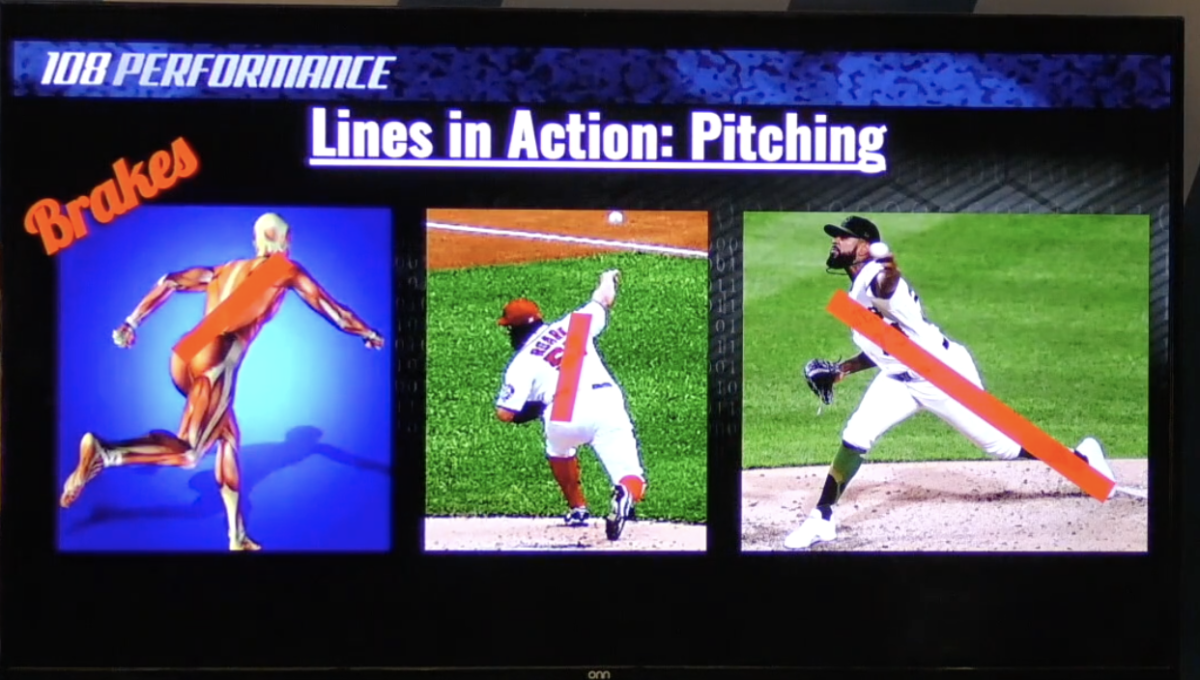

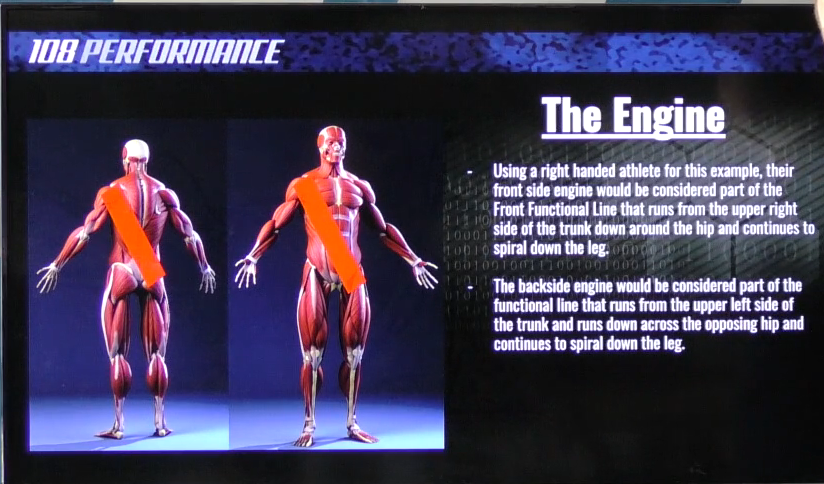

Fascia, just like connective tissue, is going to organize in accordance to the stressors under which the system is placed. These adaptations help us execute tasks with increased levels of strength, stability, and efficiency. If you were to cut open elite rotary athletes and look at their fascial patterns, you would find thick, dark X’s that run across the anterior and posterior midsection. These X’s run from the anterior shoulder, down across the torso to the opposite hip, and continue to wrap around the opposite leg. We see these X’s in elite rotary athletes because they play a huge role in developing elite rotational power. More specifically, these X’s form what we call the engine and the brakes of the system. The interaction between these two lines is where we can start our definition of symmetry.

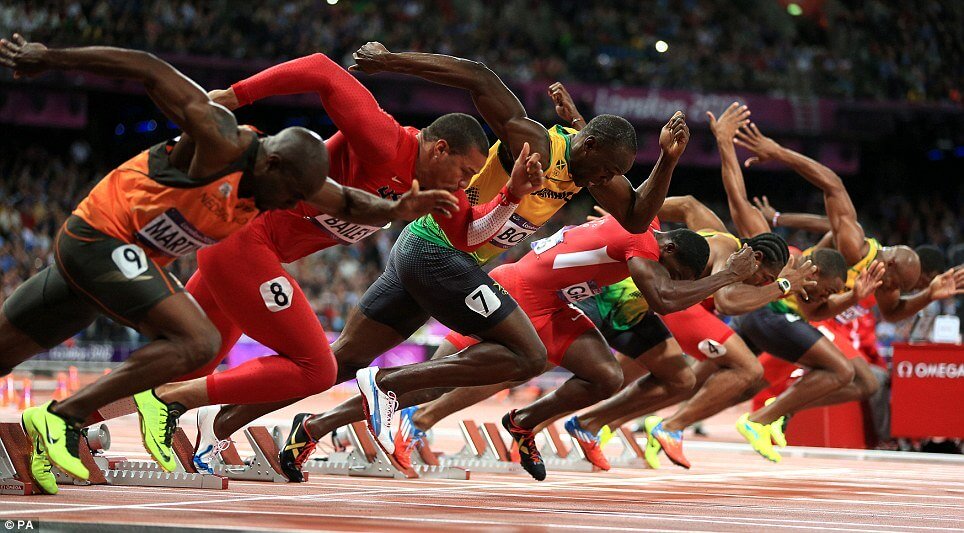

The engine line is going to run across the front functional line. It starts closest to the dominant shoulder on the upper part of the trunk, runs down across the torso to the non dominant hip, and continues to spiral down the opposite leg. The brakes follow the same pattern but start at the opposite part of the upper trunk. In terms of the skill, the engine works to get us off the starting line and creates power for the movement while the brakes give us the ability to stop, transfer force, and make sure we don’t slam into the wall after the race. In an efficient system, we need the power from the engine coupled with a strong set of brakes to keep it in check. This is where symmetrical comes from: “Symmetrical” baseball athletes are the ones who have balance between these two fascial slings. Asymmetrical athletes have lost this balance through compensatory patterns. You wouldn’t want the brakes of a Toyota Prius on your brand new Ferrari – and you definitely wouldn’t want the engine of the Prius under the hood of the Ferrari.

Balance between the engine and the brakes creates even tension that we need for an efficient sequence. If we one of these lines is weaker than the other, the other side of the system has to pick up the slack. This opens the door for compensations. Our body is going to gravitate towards the areas where we are strongest. If we favor our strong side and neglect our weak side, we’ve created a compensatory pattern. Compensations make it difficult for us to produce an efficient sequence, perform at a high level, and stay healthy doing it.

To give you feel for what uneven tension looks like, below is a video of Michael Kopech prior to his injury in 2018. Kopech is a great example of someone with an insane engine (check out a video of him pulling down 110 mph) but doesn’t have the brakes to keep it in check.

When we assess for brakes, we’re simply looking at how well an athlete is able to stop. This is a critical piece when we look at how well a hitter or pitcher is able to capture energy and transfer it up the chain to the implement. The first thing that must stop in the sequence is the pelvis. If we look at Kopech, we see his pelvis fly open and drag as he rotates to throw the ball. His front hip acceps force late in the sequence and his rear hip continues to dump forward into ball release. This is a great recipe for lower back pain – and might have been part of the reason why he got hurt.

Below is another example of a player with a stronger engine and a weaker set of brakes (as shown in the video). Notice a similar pattern where he’s late accepting force in his front hip, the pelvis flies open, and the back hip continues to dump forward, and his center of mass continues to drift forward after release.

If we look at someone who has a strong set of brakes, we notice a completely different sequence after ball release. Check out Trevor Bauer, Marcus Stroman, and Gerrit Cole below. You’re going to notice how they are able to keep their pelvis closed into landing, immediately accept force with the lead hip, and hold tension in the back hip. Instead of dumping forward, they use the back foot as an anchor point so they can get across their body. In fact, you’re going to notice their back foot never even crosses their front foot.

Now let’s revisit the athlete from above.

If we compare this pitch to the one from above, we notice a totally different deceleration sequence. In this delivery, the athlete is able to stop much more quickly and efficiently. Notice how his backside doesn’t continue to drag through after ball release and he’s able to get across his body better towards the catcher. This gives him the ability to produce the most amount of force with the least amount of energy because he’s restored balance by creating even tension in the system.

When you take an elite engine and pair it with an elite set of brakes, you can unlock some pretty special moves. Sure, we want to build a strong engine and teach our guys how to punch the accelerator but we don’t want to do it while neglecting the brakes. If you wouldn’t feel safe in a car that can’t stop at a red light, we shouldn’t feel safe when athletes our athletes can’t decelerate when they need to.

If we’re talking about symmetry in baseball athletes, the conversation must start with the X’s. While we’ll never be completely symmetrical in theory, we need to be able to find balance between the engine and brake fascial lines to optimize performance. If you’re only training one side of the equation, you’re neglecting the other side that is just as important. Like anything in life – if you don’t use it, you lose it. When you lose your brakes, you usually don’t realize it before it’s too late. Don’t wait until it’s too late to build symmetry.

The problem with our current education system

“If you think of it, the whole system of public education around the world is a protracted process of university entrance. And the consequence is that many highly-talented, brilliant, creative people think they’re not, because the thing they were good at at school wasn’t valued, or was actually stigmatized. Creativity now is as important in education as literacy, and we should treat it with the same status.” – Ken Robinson, British author, speaker, and international education advisor

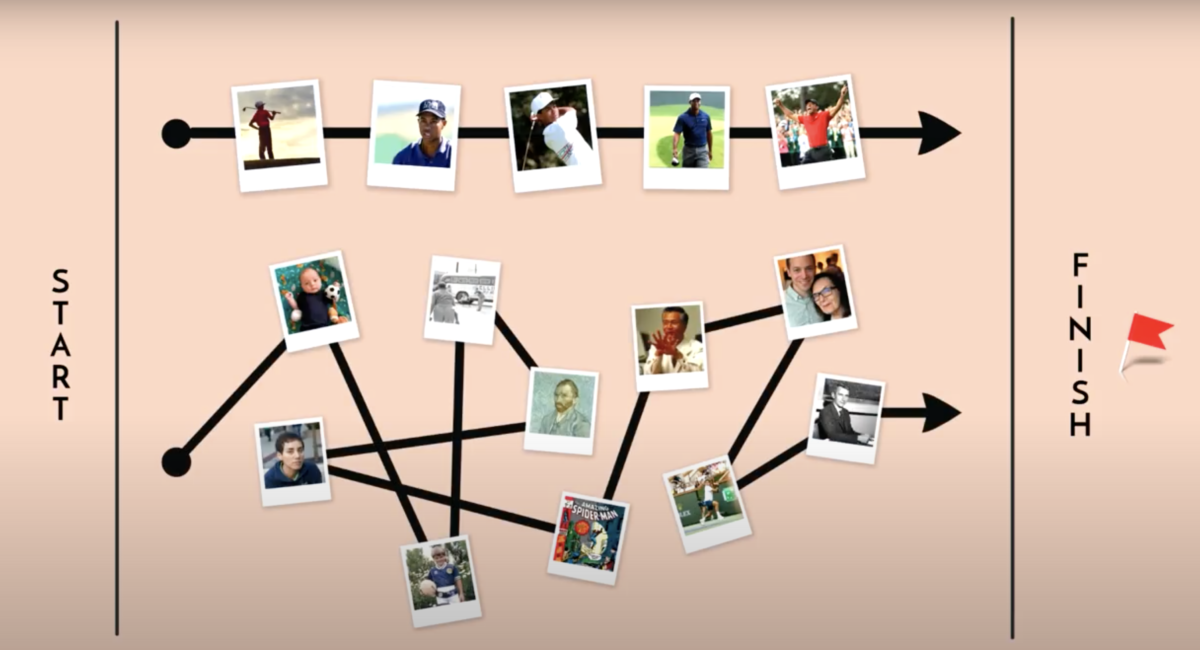

If I look back on the most influential classes I took growing up in high school, there’s one that stands alone: AP Calculus. If you know anything about me, you’d probably be a little surprised by that answer because 1) I didn’t major in math in college 2) coaches aren’t typically known for their understanding of calculus, and 3) It was the last calculus class I took in my life (and I have no interest in taking another, either). I couldn’t really tell you a thing about derivatives, the chain rule, or whatever else we learned about in that class – probably because I didn’t really understand it that well when I was actually in the class. However, there was one thing I learned from that class that I use every single day – and it has nothing to do with equations, graphs, or formulas. AP Calculus was the best class I ever took in high school because it equipped me with the ability to not just memorize information – but to think. Here’s the problem: It took my until my junior year of high school to figure that one out; and many don’t even figure it out by then. It’s also not their fault – it’s the fault of the education system we’re brought up in.

If we think about the average math class up until calculus, success pretty much depends on your ability to memorize a series of formulas, recognize which problems to use these formulas for, and hang on to this information until you can throw it out the window after the last day. Instead of learning how to problem solve, we learn how to memorize and regurgitate. This may have worked in Algebra 1, but it didn’t work for me in calculus. Instead of just searching for the magic formula that I needed, I had to understand context of the problem, what information I have, what information I needed, and how create a plan to find what I needed. There wasn’t one route I could consistently rely on to solve problems. Because of this, I started to figure out exactly what I needed to do to solve problems. I didn’t worry about a specific process I was told to execute or the steps that I needed to follow – I just used what I had and collected what I needed using strategies that best suited my strengths. In other words, my biggest breakthrough in AP Calculus happened when I stopped focusing on memorizing and started focusing on problem solving. It took an ass kicking early on to really figure that one out – and by the grace of God I was able to make it out of the class with a B. However, the grade I got in that class didn’t reflect the value I got out of it. Great grades don’t mean you learned a great deal.

Here’s the problem: Kids today think of math – and pretty much all other subjects that have sapped us of creativity – as a checklist of procedures instead of a robust system for problem solving. There is no thought, focus, or concentration when we’re blazing through a checklist and plugging in formulas based on our short term recall. The magic is in building systems – but seldom are kids taught to think and build their own. Memorizing your times tables is great when you’re working through a series of multiplication problems, but it’s not so great when we switch it up and throw division in the mix. When we’re faced with new situations, we don’t rise to our level of current procedures; we fall to the level of our systems. Systems aren’t built through memorization and regurgitation – they’re built through problem solving and slow, deep learning. Most classrooms today are teaching kids how to follow procedure; very few are teaching kids how to grapple with problems and build robust problem solving skills.

If we want to flip this equation and start building problem solvers that are better prepared to take on the dynamics of life, we have to be careful we don’t get caught up in the result. The journey should be the reward; not the destination. Memorizing procedures might help you get really good grades, but they don’t make you a really good problem solver. If anything, they probably hurt your ability to solve problems because you’re not solving anything new; you’re just regurgitating what you already know. Part of the solution to this, in my opinion, is all about tapping into our inborn childlike curiosity. We are all inherently fascinated with the world and making sense of things that are unfamiliar; no one is born with a closed mind. However – when our education system drills us with procedures and forces us to succeed through memorization and regurgitation of meaningless information, we’re stripped of our curiosity and creativity. When these two areas suffer, our ability to solve problems is crippled.

If we want to build an education system that will prepare our youth for the unpredictability of the world, we cannot praise those who excel at memorizing and regurgitating. We have to encourage kids to tap into their childlike curiosity, think problems through, experiment with different solutions, find different applications, and help them discover their own optimal way to problem solve. Throw out the formula sheets and instead hand out “how to think” sheets. They’ll forget the formulas – they won’t forget how to think (hopefully, at least). Continue reading “The Paradox of Symmetry & Problem with Education”