Thought for the Week: The Rules of Everything – by Steve Magness

- The Hype Cycle: When an idea is new or gains popularity, it follows a cycle of initial overemphasis before eventually leveling off into its rightful place

- Research is only as good as its measurement

- We overemphasize the importance of what we can measure and already know while ignoring what we cannot measure and know very little about

- We think in absolutes and either/or instead of the spectrum that is really present

- We underestimate the complexity of the human body (and almost everything else)

- We look at and analyze things from our perspective, overemphasizing what our knowledge base strength is

- Everything is cyclical

How falling behind can help you get ahead

“The challenge we all face is how to maintain the benefits of breadth diverse experience, interdisciplinary thinking, and delayed concentration in a world that increasingly incentivizes, even demands, hyper specialization.” – David Epstein, from Range

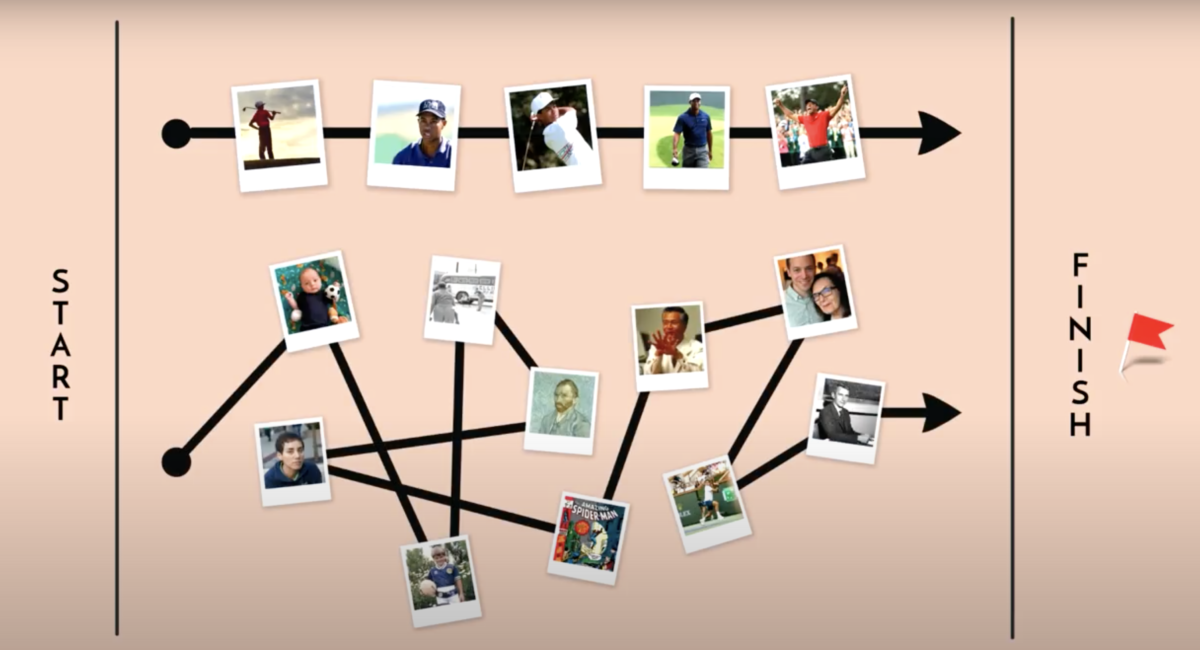

Tiger Woods was seven months old when he first picked up a golf club. By two, he entered his first tournament and won the 10U division. By three, he was shooting 48 on par nine and practicing in sand traps. Just one year later he was spending his entire days on the golf course without the supervision of his father and hustling grown men. He could beat his father by eight and by 18 he was a standout golf athlete at Stanford University. After two years at Stanford, Woods joined the PGA tour in 1996 and started his professional career. By 21 years old he was the best golfer in the entire world. At 44 years old he is one of the greatest golfers this game has ever seen and has amassed 109 professional victories in 24 years on the tour. Tiger’s destined story to greatness is the epitome of Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000 hours rule: Mastery of any domain requires 10,000 hours of focused practice. Tiger’s dad sure didn’t waste any time getting him started.

Now let’s look at a different story. This young man wasn’t really interested in sticking to a specific sport early on. In fact, there aren’t too many sports that he didn’t try – as long as they involved a ball. While his mother coached tennis, she wasn’t really interested in teaching him because his return serves weren’t normal. In fact, the only advice she really gave him was to stop taking it so seriously. When his tennis coaches asked him to move up a level to play with the older boys, he declined because he was more interested in hanging out with his friends afterward and talking about pro wrestling. When he finally gave up the other sports, his competitive peer group had long been working and refining their craft with performance coaches, strength coaches, and nutritionists. However, starting late didn’t really seem to hamper this young man’s long-term development. In fact, Roger Federer managed to develop into a fine tennis player; he’s not too worried his peers got a head start on him.

While many know about Tiger’s destined route to greatness, very few known about Federer’s unique path to stardom. When we look at both paths, Woods and Federer represent two opposite poles when it comes to the development of mastery. Woods is the poster boy for early sport specialization; Federer is the example of the benefits of late specialization. Both represent the elite of the elite in their respective sport, but each took a completely different route to the top. While it’s easy to romanticize with Tiger’s story, it doesn’t mean his route is the most optimal path for everyone. In fact, some would argue that Federer’s path to the top is more practical and optimal. One of these guys is David Epstein.

In his recent book Range, Epstein dove into Federer’s unlikely path to excellence by examining the amount of deliberate practice elite performers engaged in growing up as compared to their non elite counterparts. When he looked at the research, he found that elite athletes actually performed less deliberate practice early on. The elites only surpassed them when they reached 15-18 years old.

Instead of diving into deliberate practice earlier, elite athletes underwent what researchers call a “sampling period.” This sampling period is where kids tried a lot of different sports in an unstructured/lightly structured environment in which they were able to gain a wide range of physical proficiencies, get a feel for their strengths and weaknesses, and use these experiences to eventually narrow in one something later in their life (remember the study on the 2014 German World Cup team?). This sampling period is not just specific to sports; Epstein found it in plenty of other fields too.

When researchers compared the earnings of postgraduate students from England who early specialized in a specific field and students from Scotland who delayed their route to specialization, they found the English students had a short-lasting head start. The English students earned more early on because of the advantages of their specialized knowledge base, but the Scotts surpassed them in the long run as they were more likely to figure out a field that best matched their interests and strengths. When they found an environment they were more likely to succeed in, they showed higher interest levels, were more likely to persist through challenges, and ended up making more money in the long run. The English students who were forced into a career path early on could not sustain their head start – they hadn’t given themselves enough range to figure out what best made sense for them.

The Scottish students and Federer are not the only ones who have had success using the generalist/late specialization model. Vincent van Gogh had gone through five different careers – all unsuccessfully – prior to his 30th birthday. It wasn’t until he picked up a book in his late twenties called The Guide to the ABCs of Drawing that he started to figure out his true career path. Gunpei Yokoi used his passion for various hobbies to develop lateral thinking that lead to the creation of the cutting-edge technology behind the Nintendo Gameboy. When researchers examined what separated the best comic book creators from the rest, they found the amount of comics created, experience, and the resources at their disposal all had no impact at all. The only thing that mattered was how many different genres they worked in. “Where length of experience did not differentiate creators,” said Epstein, “Breadth of experience did.”

“Parents want their kids doing what the Olympians are doing right now, not what the Olympians were doing when they were twelve or thirteen.” – Ian Yates, British sports scientist and professional sports coach

So if the majority of fields need an early sampling period for success later on, why did Tiger’s route work? Epstein explained this by dividing learning environments into two different categories: kind learning environments and wicked learning environments. Kind learning environments deal with consistent and repeatable patterns where the feedback is immediate, extremely accurate, and rapid. There are defined boundaries, consequences are quickly apparent, and similar challenges occur repeatedly. Examples of kind learning environments include golf and chess. They’re coined as “kind” because learning is pretty straight forward. Improving your short game isn’t too complex – just grab your club, a bucket of balls, and head out to the green. The more you practice it, the better you are going to get at it (assuming the practice is focused). When you combine a generational talent with an insatiable work ethic, a clear route to the top, and thousands of hours of practice, you get Tiger Woods.

Wicked learning environments are the opposite; the rules are unclear, there aren’t repetitive patterns performers can consistently rely on, feedback isn’t always obvious, can be delayed, or is inaccurate as a whole. Entrepreneurship is a great example of this – there aren’t any rules or boundaries you need to work within, your efforts early on won’t always yield subsequent results, and you don’t have any previous patterns to rely on to guide your future decisions. It’s demanding, it’s chaotic, and it’s anything but kind. It’s also what most learning environments actually look like. Golf and chess don’t turn out to be the majority; they are the exceptions.

Very seldom do we engage in activities where there is a clear and defined route to the top. Most learning environments are very challenging (not saying golf or chess aren’t), unpredictable, unforgiving, and they require more than just deliberate practice to figure out. Some of the greatest discoveries we’ve ever seen happened in the absence of prior knowledge, patterns, and thoughts. Kepler didn’t have any previous research to help guide his theory that planets further away from the sun moved slower. He had a hunch that he brought to life using empirical observation, logic, thinking across different disciplines, and connecting the gaps in his understanding through the use of analogies. If your understanding isn’t robust enough to withstand the rigors of a wicked environment, it will be exposed when you’re placed into a situation that is unfamiliar. The best chess players in the world perform no better than novices when they’re placed in situations they don’t recognize from previous experience. Learning isn’t about going through a checklist of procedures; learning is what happens when those procedures get thrown out the window.

While learning in wicked environments is difficult and can be frustrating early on, it provides great long term returns. To understand this, let’s think about the differences between learning math in a blocked/repetitive environment (kind) and in a variable/unpredictable environment (wicked). When learning in kind/predictable environments, you’re able to lean on previous experience through pattern recognition. It’s easy to figure out 6×6 using previous recall when all you’ve been doing lately is hammering down on your multiplication tables. When learning in variable and unpredictable environments, you can’t rely on previous recall. Going from addition to division to multiplication is a hair trickier than just honing in on your times tables. Instead of just spitting out information from your short term memory, you need to actually create a strategy where you differentiate types of problems and design actionable strategies to attack them individually. Instead of memorizing procedures, you have to build long term strategies. The returns on these strategies are significant; especially when the conditions for the problem inevitably change.

So what’s the point of all this?

The point is this: Deep learning is slow. It takes time to build a robust skill set and a thorough base of knowledge required to become an effective problem solver. We praise the Tiger Woods of the world who get off to an early head start, but what we don’t realize is how rare these cases actually work out. Imagine if you forced Roger Federer to just play tennis as a kid and stripped him of his ability to play other sports and spend his free time hanging with his buddies after practice. He’d probably grow to hate tennis so much that he’d quit before he even got into high school (hint: parent-induced burnout is real). The generalists and the late specializers who take their time to dabble in different fields early on are the ones who usually find the best fit in the long run.

If we think about it, our greatest advantage as a species over machine learning is not the ability to narrowly specialize; it’s the ability to integrate broadly. When we’re dealing with open-ended real world problems, we crush machines. Machines can specialize in ways that we cannot but they also cannot browse through a wide range of fields, draw parallels between them, and find ways to solve problems by using experiences from other domains. Our ability to navigate various disciplines and make connections between them is a large part of what makes our learning systems incredibly unique – you’d be wise if you took advantage of it.

“Some tools work fantastically in certain situations, advancing technology in smaller but important ways, and those tools are well known and practiced. Those same tools will also pull you away from a breakthrough innovation into an incremental one.” – Andy Ouderkirk, material engineer at Oculus Research

While some activities like golf and chess have more direct routes to success, the majority of careers do not. Our ability to navigate wicked learning environments comes back to our ability to effectively solve problems. Building a wide range of knowledge from multiple domains gives you the framework you need to see the big picture, break things down, and defer to other domains who can provide you with more detailed expertise. Specializing in one area early on may delude you into thinking you have a head start, but in reality it blinds you from other areas of benefit and ultimately prevents you from getting out of your own way. Charles Darwin’s greatest breakthroughs represented “interpretative compilations of facts first gathered by others.” He was, in Epstein’s words, “A lateral-thinking integrator.” When the path is no longer clear, the same routines will no longer suffice. This is where the generalists reign king.

Epstein’s greatest piece of advice can be summed up in three words: “Don’t feel behind.” He said, “Compare yourself to yourself yesterday, not to younger people who aren’t you. Everyone progresses at a different rate, so don’t let anyone else make you feel behind. You probably don’t even know where you’re going, so feeling behind doesn’t help.

“Approach your own personal voyage and projects like Michelangelo approached a block of marble, willing to learn and adjust as you go, and even to abandon a previous goal and change directions entirely should the need arise. Research on creators in domains from technological innovation to comic books shows that a diverse group of specialists cannot fully replace the contributions of broad individuals. Even when you move on from an area of work or an entire domain, that experience is not wasted.”

Got to rember that, if nothing else it will make a kid feel better about himself. With a little luck work a little harder.