See Part I of our recap from Bridge the Gap 2020 here.

Our very own Will Marshall took the stage at Bridge for the first time breaking down the last eight months at 108 Performance. With the shutdown in March, we were forced to close the doors at our Tustin shop and had to migrate towards an online training model. Will’s presentation dove into exactly how we were able to create the best possible experience for our athletes despite being unable to train in person.

To approach it the same way we would in the shop, Will kept five things in mind:

- Create a shared understanding between the coach and player

- Promote creativity and collaboration

- Teach athletes how to problem solve and think for themselves

- Empower our players to take ownership of their careers

- Get real on field results

When breaking down film, Will broke down all of the things they looked at into three big buckets.

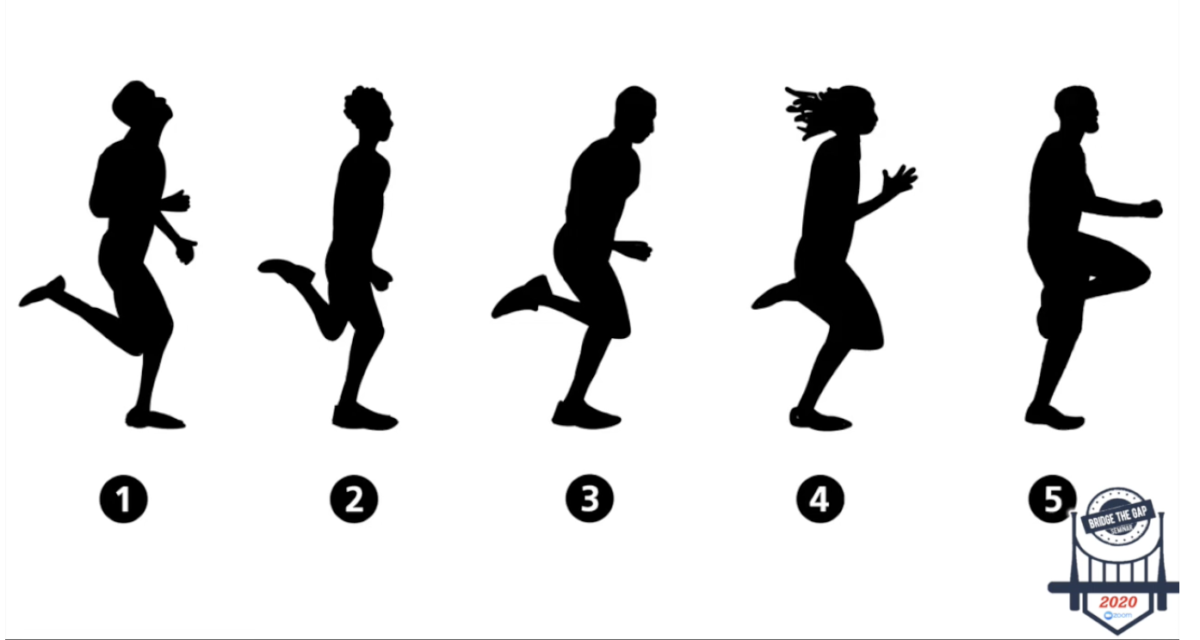

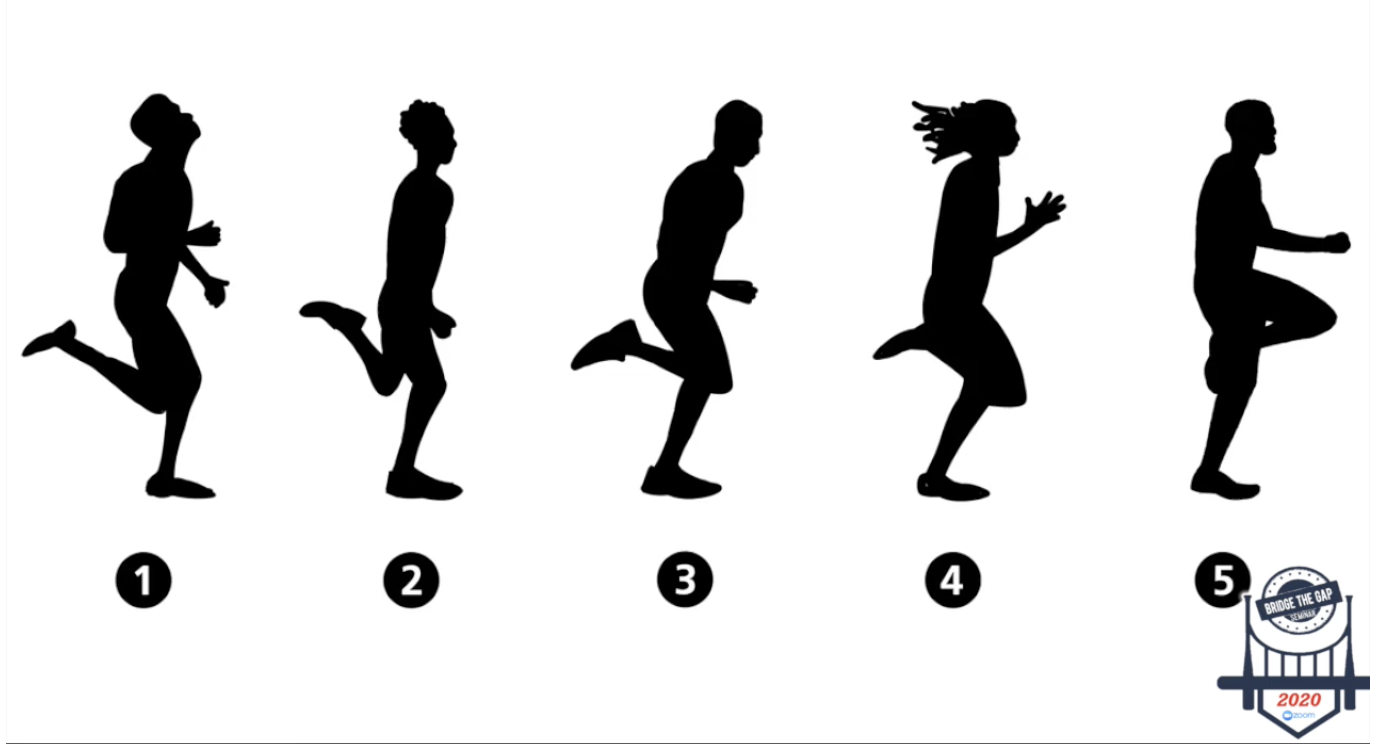

- Is the player able to move sideways?

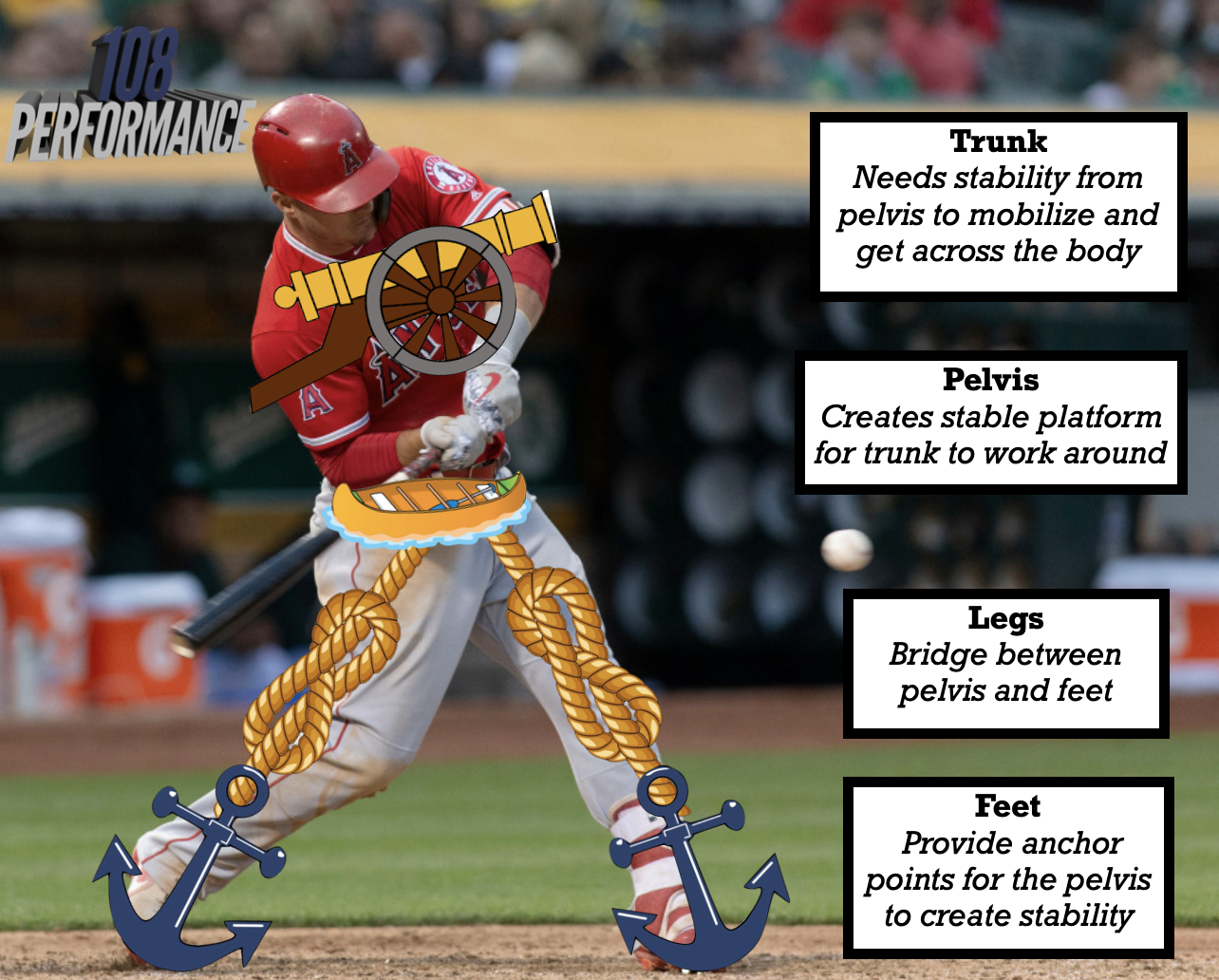

The forward move in hitting or pitching is where we tend to see a lot of energy leaks take root. A lot of these leaks get cleaned up when kids learn how to hinge, stay centered, and gain ground keeping their pelvis closed. Success in baseball comes down to how well we move a weight through space. Getting into positions of leverage at foot strike is a great place to start.

- Can the player stop?

Baseball is a rotational sport. In order to rotate well, players must be able to stop their forward momentum and create a stable platform for the pelvis. Stability down low gives us the ability to rotate well up top. Guys who can’t stop well when their front foot comes back down to earth have a tough time producing force in small windows.

- Does the player rotate well?

As mentioned above, baseball is a rotational sport. Really good players rotate really well. Teaching guys how to get their pelvis, trunk, and arm all rotating in unison around their center of axis is a pre-requisite for performing at a high level. Guys who can’t don’t typically perform very well.

Interested in hearing more from Will’s presentation? You can get free access to it here.

Our MLB Executives and Coaches Panel was a big hit from the weekend and featured Bobby Basham – Director of Player Development Chicago Cubs, Josh Boyd – Assistant General Manager Texas Rangers, Donnie Ecker – MLB Hitting Coach San Francisco Giants, Brian DeLunas – previous Bullpen Coach Seattle Mariners, and Don Wakamatsu – Bench Coach Texas Rangers.

During the conversation, something talked about was the integration of scouting and player development within Major League organizations. Basham made a really good point about this by referencing a statement from Erik Spoelstra – head coach of the Miami Heat. Spoelstra credited a lot of the team’s success this year to the fact that their organization is aligned really well top to bottom. This is where Basham believes baseball organizations can create a competitive advantage going forward. Drafting won’t be about just picking the best players. It will come down to finding the right players that you know your coaches will be able to get the most out of with their current skill set.

“Gaining trust isn’t about knowing what their grandmother’s first name is. It’s about showing that player you can help them get better.” – Donnie Ecker, MLB Hitting Coach San Francisco Giants

Getting the most out of players is something Donnie Ecker has had a track record of since first entering professional baseball. For him, one of the biggest things that’s helped is the ability to build trust with his players. That trust is largely earned by showing each hitter how he can help them solve a problem. “Gaining trust isn’t about knowing what their grandmother’s first name is,” said Ecker. “It’s about showing that player you can help them get better. If I can’t help them get better they’re not going to trust me.”

Don Wakamatsu added to the conversation by talking about the importance of building a winning culture at the minor leagues. Instead of just viewing AA and AAA as stepping stones to the big leagues, Don believes minor league teams should strive to develop championship caliber clubs. The focus shouldn’t just be on developing individuals. Players need to know winning is important from the moment they first sign a big league contract. If the expectation is to win in the minor leagues, that expectation is going to be ingrained by the time they reach the big leagues.

On the strength side, Zach Dechant, Baseball Director of Strength and Conditioning at TCU, spoke about the integration of the weight room with game performance. Of note, Dechant spoke to how the nervous system doesn’t always select the right muscles for the skill and as a result, muscles end up doing the wrong jobs and become inhibited. “Being strong biomechanically in a muscle doesn’t mean it’s neurologically preferred by the body,” said Dechant.

Athletes who struggle swinging or throwing but run 6.7 60s and can ‘squat a house’ know how to turn their glutes on. They just can’t do it when it comes to the skill. It’s not an activation problem – it’s a movement problem. As a result, movement remapping can’t just focus on activating certain muscles. It must also involve building a new model for the movement in the central nervous system so the right muscles can be activated during the skill.

“Being strong biomechanically in a muscle doesn’t mean it’s neurologically preferred by the body.” Zach Dechant, Baseball Director of Strength and Conditioning TCU

Zach also explained that through his observations he’s found his best athletes are the best compensators. At TCU, some of the elite athletes Zach works with struggle with basic movement competency such as pelvic control and rotation. They might be really good at throwing or swinging, but it doesn’t mean they do it optimally. Our bodies are hardwired to find a movement solution for any given task. The problem is we’re only really concerned with task completion – not necessarily task efficiency. Your best athletes are really good at solving problems in the context of sport, but they’re not always good at coming up with the best solutions. This is where good coaches must be able to step in and define what is optimal, allowable, and not optimal for that athlete.

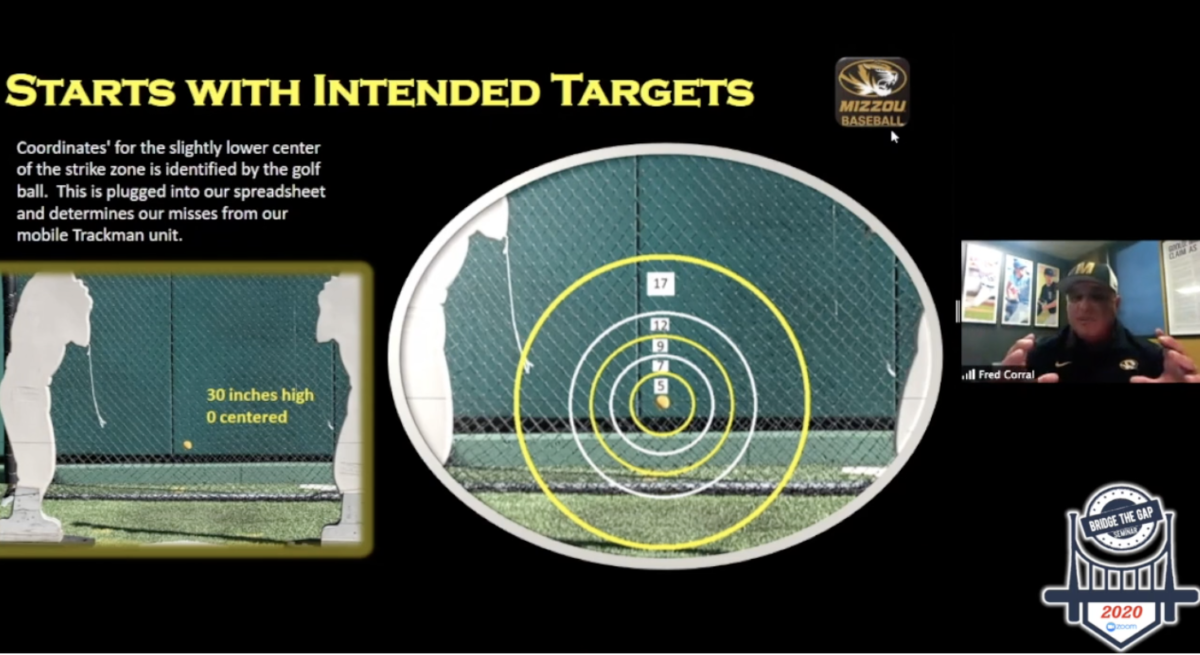

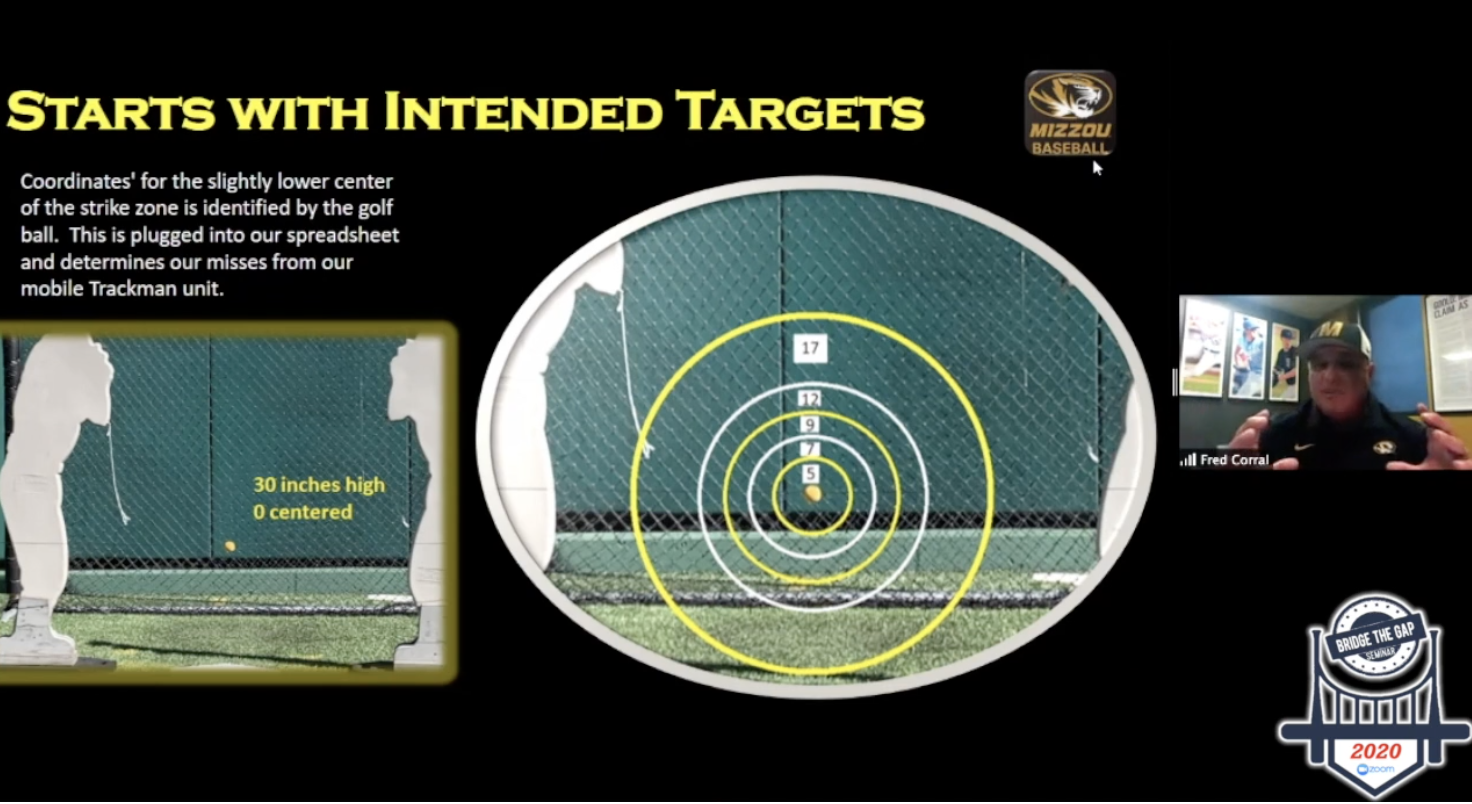

On the field, Fred Corral, Pitching Coach at the University of Missouri, shared how his pitching staff has made big strides using their unique process to measure command. Prior to each bullpen, Corral will set up a small yellow ball that is located in a specific part of the strike zone. Pitchers are instructed to try and locate pitches as close to that yellow ball as possible. During the bullpen Corral uses Trackman to collect data on every single pitch and see how far each one missed the yellow ball. After each session, they’ll sift through all of the pitches thrown and come up with an average miss for that day. This gives them a benchmark number to improve on for their next training session. While command has typically been quantified using strike percentage, Corral’s system goes even deeper by measuring exactly where a pitch was in relationship to a specific target. This gives pitchers much better feedback on their ability to locate the baseball and if their training is helping them improve this.

Additionally, Corral has rethought his perception of home plate. Instead of looking at it as a pentagon, Corral likes to view it as a circle. Viewing the plate as a circle as opposed to a pentagon helps his players understand they can throw their stuff across the plate from different angles as opposed to just the front of the plate. This is especially beneficial for players who throw from the arm side portion of the rubber. Corral sees tremendous in moving to the arm side part of the rubber because it creates a difficult angle for hitters to pick up the ball. It’s either being released at them or slightly behind them. When you can teach these guys they don’t have to throw their stuff across the front part of the plate, you’ve given them the freedom to use their slot to their advantage.

With the current trend to sell out for velocity, Corral’s presentation is a great reminder that pitching is much more than just lighting up a number on a radar gun. Great pitchers are able to command the baseball, throw from different angles, and find as many ways as possible to keep hitters off balance. Velocity it just one of these.

Interested in more? Check out all of these full presentations and more here.