If I think about what it means to be a “generational athlete,” some of the words that come to my mind include:

- Game changer

- Excellence

- Cold-blooded

- Intense

- Clutch

- Timeless

- Rare

- Pioneer

- Precise

- Graceful

Here’s what that list would look like if I were to eliminate all of those words except for one:

- Game changer

Generational athletes get their name because their impact on the game transcends generations. They took something so complex, boiled it down to its most simplest form, and used their ability to put their own unique touch on it. They’re creators, inventors, and pioneers. They opened our eyes to a skill set and style of play we had never seen before – and the game, as we know it, was never the same after them. It was powerful, it was precise, and it was done with such grace – almost making us forget how difficult it was.

These types of players don’t come around too often, but when they’re here they’re difficult to miss. It’s the Jordans and Birds in basketball, it’s the Gretzkys and Crosbys in hockey, it’s the Montanas and Bradys in football, and it’s the Griffeys and Bonds in baseball. What they did on the playing field was so raw and unique it couldn’t possibly be replicated by any ordinary athlete. When everyone was stuck trying to make blue, they were two steps ahead making green. They’re the types of players we tell our grandkids about because it’s one thing to read about them in the history books – it’s another to be lucky enough to have actually seen them with your own eyes.

In 2012, baseball got their first real look at two players who had this kind of potential.

The comparisons were impressive.

People were calling them the Mays & Mantle, the Ruth & Gehrig, and the Griffey & A-Rod of this generation of baseball. They had the bat to ball skills to spray line drives at command, the power to make ballparks look small, the range and arm to take away bases, and the confidence in their abilities to go toe-to-toe with the best in the game. Both were destined to make the bigs as teenagers and they weren’t going anywhere once they got there. When it was all said and done, the sky was the limit for what they both could achieve. It wasn’t a question of if they were going to Cooperstown; it was a question of who would have the best resume when they were eligible.

Their names were Bryce Harper and Mike Trout.

Now let’s fast forward the clocks to 2020. Harper and Trout both have had seven full big league seasons under their belt. They’ve both inked multimillion dollar deals worth in excess of $300 million, won an MVP award, and solidified themselves as cornerstone franchise players.

But, this doesn’t tell the whole story. Both Harper and Trout had the ceilings to become generational athletes, but only one has had the production to match it. The other has largely been a disappointment.

Trout hasn’t just surpassed Harper as the better player – he’s blown him out of the water.

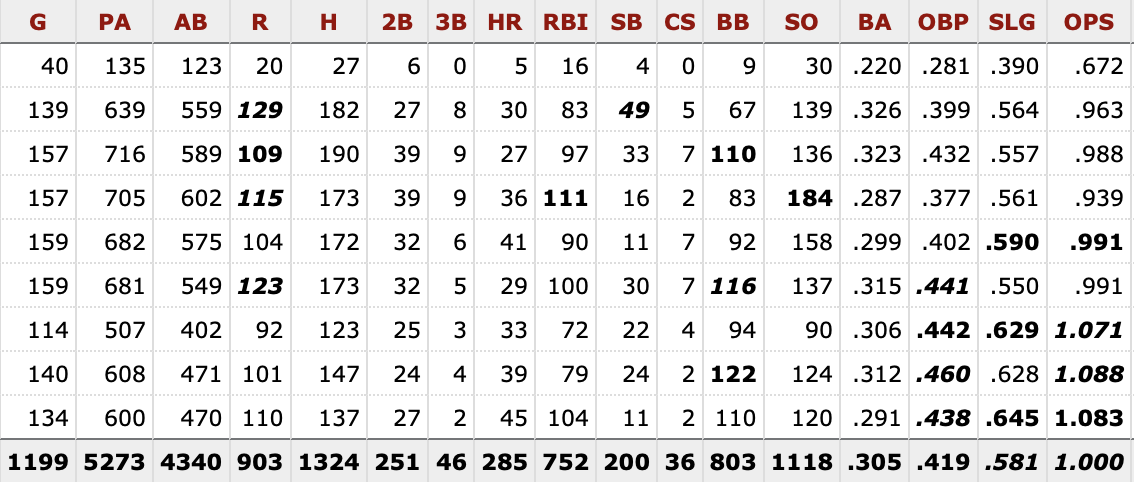

This is what Trout’s numbers look like:

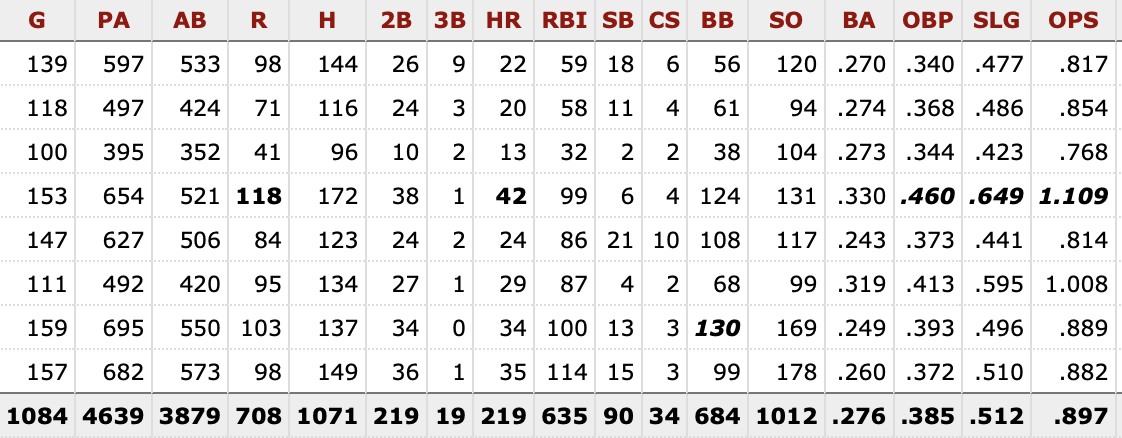

This is what Harper’s look like:

Through seven full seasons, Trout has outperformed Harper in just about every single statistical category possible. He’s collected 253 more hits, belted 66 more homers, stolen 110 more bags, and boasts an OPS that is 103 points higher. He’s won seven silver sluggers, three MVPs (he probably should have three more), and when he hasn’t won the MVP he’s finished second every single year except for his rookie year and 2017 (he missed a good chunk of the year to injury). Harper has had just one silver slugger, one MVP award, and hasn’t received top 10 MVP votes in any other season.

In 2019, Trout finished third in the MLB in WAR with 8.3. Harper finished tied for 59th – and he made more money than 58 of the players in front of him. In fact, Trout’s 10.5 WAR from his rookie season exceeds Harper’s 9.7 WAR from his 2015 MVP season – his best statistical season to date. Just think about that: At 20 years old, Mike Trout put together a better season in terms of WAR than Bryce Harper has put together in his entire career.

If that doesn’t convince you of Trout’s dominance, Harper has failed to bat above .274 or post an OPS north of .900 in every single season outside of 2015 and 2017. Trout hasn’t posted an OPS under .900 in his entire career. In 2014, Trout set career lows in batting average at .287, OPS at .939, and struck out a career-high 184 times.

He won the MVP that year.

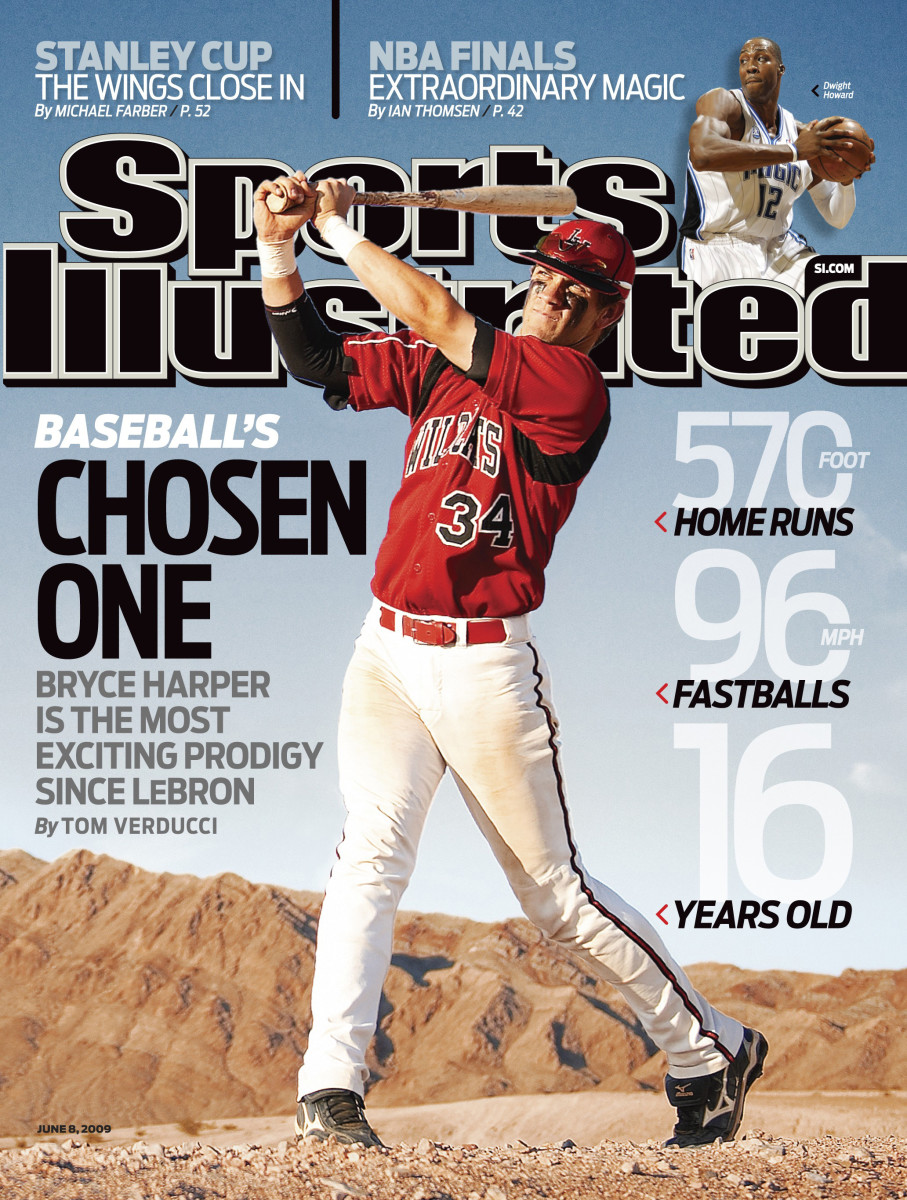

Here’s the thing: Bryce Harper should be doing what Mike Trout already is. He was the one who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated at 16, won the Golden Spikes award at 17, and became the third youngest player ever to be selected number one overall. He should be in the MVP conversation every single season and churning out numbers that put him right next to Trout as one of the best hitters in the game. Instead, he isn’t even in the conversation – let alone one of the top 10 hitters in the game.

Bryce Harper isn’t “Baseball’s LeBron James” – Mike Trout is.

However, this doesn’t mean Bryce Harper can’t be as good as Mike Trout. In fact, he should be matching Trout’s production – possibly even exceeding it – because we’ve seen what he looks like when he’s on. We’ve seen the spurts of dominance in ’15 and ’17 and we know he’s capable of putting together seasons where he belts 40 homers, drives in over 90, and bats above .300. We’ve seen the raw power and the way he can impact the game at the plate with just one swing of the bat. We just haven’t seen it nearly as much as Trout – and Father Time is ticking.

If we look at the Harper clips above from the four different seasons, we notice four different moves. While every player is going to have some sort of variability built into their swing, the best work within a narrow bandwidth. Harper’s bandwidth is monstrous. When your bandwidth gets bigger, it becomes more difficult to manage variability because you have a wider range of movement solutions to pick from. If you’re presented with various choices to go out to dinner, you’re going to make a much quicker decision when presented with two restaurants as opposed to five. Harper’s constantly choosing from seven different restaurants when he should really narrow in on the two he enjoys the most. He’s failed to find consistency because his bandwidth makes it really difficult for him to find consistency; and his numbers reflect it.

If Harper really wants to become the best player this game has ever seen, he doesn’t need any more tinkering, adjusting, forcing, and compensating. He needs to get back to the basics and figure out how to create his best move more often. We’ve only seen his best moves two out of the seven seasons he’s been in the league so far. While he’s done well enough to earn himself a pretty good pay day, he hasn’t nearly lived up to his prophecy as a “once-in-a-lifetime” player.

Trout, on the other hand, has met those expectations and exceeded them. If you want to know why, the proof is in the tape.

If we look at his moves from his rookie year and compare them to how he moved in 2019, we notice two really efficient swings that are nearly identical. Trout doesn’t just move really well – he moves really well consistently. He’s not changing, tinkering, or finding new ways to reinvent the wheel the way Harper has. He’s found really efficient moves that he replicates more than anyone else. He doesn’t get off three different swings; he gets off one – and it’s almost always his best one.

When you can consistently get your A swing off, you give yourself the biggest window possible to do damage on pitches in your hammer zone. When your moves are constantly changing, it’s difficult to find your A swing and repeat it because there’s no consistency. If you can’t get your best swings off on pitches in your hammer zone, you cripple your ability to consistently do damage at the plate. You will always be at the mercy of the moves you bring to the plate. The best hitters don’t just move well – they move well more often than anyone else.

Trout has had consistent success because he has found consistent movement solutions at the plate. Harper has not had consistent success because his moves aren’t even close to consistent – but the right ones he needs are already there.

If only he could figure out what he does when he’s on, what he has trouble with when he gets off track, and what he needs to think about to get his A swing off more often.

We might have some ideas on this – but they’ll have to wait for next week. One blog doesn’t do this project enough justice.