I was recently able to have an interactive discussion with baseball coaches and players from the south central PA area. The discussion was centered around developing the complete pitcher by eliminating common training myths and misconceptions. The discussion also featured a presentation from Monica Johnson, PT, DPT, of Phoenix Rehabilitation who gave tips from the perspective of a physical therapist to help keep athletes healthy.

We were able to cover 24 things that you should NOT be doing if you want to develop high level arms. I will go over items 1-11 in this part of the blog along with the presentation from our physical therapist.

1. Get to a Balance Point

A “balance point” refers to when the pitcher lifts his lead leg and gets to a position of zero lateral movement before continuing his motion down the mound. This is a very common teaching point when first learning how to develop the lower half in young pitchers. When talking about balance points, I always come back to a question from Wayne Mazzoni – pitching coach at Sacred Heart University: “If you had someone kneeling five feet in front of you, what would your delivery look like if you wanted to punch them in the face?” When kids show you what their best punch looks like, you’ll notice none of them come to a “balance point.”

Teaching a balance point does not make any sense when developing pitchers simply because no one gets to a balance point. When we look at several big league arms, we notice none of them get to a position where they can hold their center of mass over the rubber if you stopped their delivery after leg lift. As Mazzoni says, we want to get away from the rubber. As the lead leg comes up, the athlete’s center of mass should begin to shift down the slope of the mound. This is not a rushed move down the mound – it’s a controlled gathering of energy. Every athlete is a hair different in regards to how they do this, but none of them create power by getting to balance.

Nolan Ryan, Gerrit Cole, Trevor Bauer, and Corey Kluber all getting away from the rubber using a controlled gathering of energy (videos from @pitchingninja).

Ben Brewster of Tread Athletics wrote a very good article about this and the advantages of getting away from a balance point. He describes a better move down the mound as “the drift” – the initial forward move that occurs during leg lift. He explains the benefits of it saying:

“The drift is a “free” movement that hardly costs any energy , and allows you to save that available hip/knee

extension and hip abduction until the majority of it can be directed laterally into the ground (once the center of mass has actually shifted away from the rubber).

“I liken this to standing directly next to someone and trying to knock them over with your hip, to standing 6-8 inches away from them and trying to knock them over with your hip – the increase in efficiency and force is substantial, so saving up your rear leg until all of that force can be directed where you want it is probably more effective than muscling your way down the mound.”

Ben has a few theories on why the balance point has become so prevalent. Like all bad information, it comes down to a misinterpretation of what guys may unconsciously do. Pitchers with athletic deliveries may not think about drifting down the mound. They just figured it out through trial and error without ever thinking about what actually happens at leg lift. This move is also tough to see from the rear camera angle on TV. From behind, it may appear that some of the best pitchers come to a balance point. It’s only until you see them from the side that you realize what’s actually going on.

His last point made a lot of sense to me: It’s easier to teach balance points. He explained saying:

“You can take a group of 12 year olds and work on an up-down-out lower half in a very systematic and repeatable way. Try to teach a 12 year old how to move dynamically through his leg lift – you’re going to have a hard time making much headway in all but the most athletic kids. Balance is easy – and to some extent, it might help create more repeatable mechanics in the majority of kids who are falling all over the place when they throw. But just because it lowers a 12 year old’s walk rate doesn’t mean it’s what the majority of the hardest throwers in the world do.”

Sapping an athlete’s ability to create linear momentum down the mound is an energy killer. Building a high velocity delivery cannot be accomplished by teaching static positions of balance. Pitchers should be trained to move like athletes – not robots.

Pitchers should be trained to move like athletes – not robots.

The best way to get athletes away from a balance point is to stop teaching it. Kids will naturally get away from a balance point if you allow them to move fast and throw hard. If you have kids who have more ingrained patterns, below are a few ideas that you can use to create a better sequence.

- Starting on slanted surfaces (slope of the mound, slanted boards)

- Walking windups

- Shuffle throws off the mound

- While this one is less specific to the delivery, it helps athletes get a feel for accelerating their center of mass down the mound and can unlock some athleticism in the process

2. Drop and Drive

Athletes need to be careful with the “drop and drive” style. Drop and drive refers to the athlete getting to a position of balance and then driving with their back leg towards the plate. If the athlete is working into his back leg but not going anywhere, he’s creating a cost-effective move that is difficult to execute. Instead of using linear momentum to create velocity, your arm is at the mercy of how much you can one-legged squat. The drive portion of the cue can also create a quad-dominant delivery – something we’ll talk about below.

3. Push off the Rubber

4. Get a longer stride

Push off the rubber is a commonly used cue when coaches are teaching kids how to use their lower half to add more velocity. While it’s well intentioned, the average interpretation and application of the cue creates bad moves that inhibit an athlete’s ability to use their glutes and produce an efficient rotary sequence. When athletes are told to push off the rubber, you’re going to commonly see kids shift the weight in their back foot to their toe as they try to push off and create extension with their back leg. This creates what is called a quad-dominant move. Instead of staying into the heels and utilizing the glutes, the less-powerful quads are turned on to drive lower body movement (note – you want to keep the entire foot grounded, not just the heels). This gives athletes the illusion that they’re creating more power from the lower half by leaping down the mound, but instead they’re throwing off the rest of the sequence and not utilizing the strongest muscles in their body.

You can identify a quad dominant move by looking at the back knee and foot in the delivery. Guys with a quad dominant delivery will leak their rear knee out over their toe and the heel will come out of the ground prematurely. This can cause guys to start to step across their body and lose good direction to the plate (emphasis on good direction). Below are a couple of examples of quad dominant deliveries.

An example of a quad-dominant delivery. Notice the back heel comes out of the ground prematurely and the weight shifts to the back toe (Image Source).

A glute dominant move is created when an athlete’s butt sits behind their heels. The entire back foot stays connected to the ground for a long period of time. The back leg does not “triple-extend” the way you were to if you executed a vertical jump. The rear glute mirrors the slope of the mound (a Lantz Wheeler quote) and drives the center of mass forward to create a powerful rotary sequence. By letting the big guys do the work, athletes are able to create energy efficient positions required for a powerful delivery. The “tall and fall” style prevents athletes from doing this and can have a negative impact on velocity, arm health, and command.

Kenley Jansen showing a glute dominant move where his back foot stays connected to the ground (from @pitchingninja).

A rear view of a glute dominant move where the butt sits behind the heels (Image Source).

Two of the hardest throwers on the planet using glute dominant moves (from @pitchingninja).

Wes Johnson, pitching coach with the Minnesota Twins, explained the importance of a glute dominant move down the mound in a recent article saying:

“We know that hip speed is a function of velocity and command as well. Hip speed is generated through your glutes and we’re just trying to activate the glute medius. We’re trying to get the glute med to activate first instead of your quadricep because when a guy’s quadricep activates first, his hip speed goes down. So we’re just trying to activate the glute to get the hips to rotate faster to get command and-or velocity, whichever one.”

Randy Sullivan from the Florida Baseball Ranch elaborated on this idea in a blog article saying, “The quads are designed for one thing, extending the knee. As such, the quads are excellent for pushing and leaping forward, but they are not good at sitting, riding and rotating. That’s the job of the glutes.”

Below are lower half transformations from Twins pitcher Kyle Gibson and White Sox pitcher Lucas Giolito. You’ll notice both pitchers used to have quad-dominant deliveries and now are able to utilize their glutes much better. Gibson had a career year in 2018 after making these changes setting career-highs in ERA (3.62), IP (196.2), and K (179). After struggling in 2018, Giolito became one of the league’s hottest arms in 2019 making his first All-Star appearance and fanning 228 batters in 176.2 IP.

Notice Gibson’s quad dominant move (left) causes him to step across his body and hurt his ability to attack guys to his glove side (video source).

Giolito’s new glute dominant delivery helped tighten up his arm action and helped propel him to an All-Star caliber season (from @pitchingninja).

Push off the rubber is a cue that can be used when coaches are trying to create a longer stride (why I broke down these two misconceptions together). Research has shown some high velocity throwers generate an exceptional stride length (see Chapman analysis) in relation to their height. As a result, coaches started to think that a longer stride equated to ball velocity. Kids started to sell out for stride length at the expense of a pushy, quad dominant move down the mound. Instead of looking at the actions and the moves that created a “bigger stride,” most coaches just jumped to the “reactions” of a powerful, efficient delivery. Big league pitchers don’t throw hard because they have bigger strides – they throw hard because of the sequence that creates a bigger stride.

Sullivan spoke about this relationship saying:

“Back in the early 2000’s it became very popular among pitching “experts” to say, “stride length should be at least 120% of body height. There was some merit to the observation. Many hard throwers do have front foot landing points farther away from the rubber than their softer throwing peers, but it has nothing to do with the length of their stride. They land further out because they ride their glutes longer, thereby creating greater and later (ground reaction force), giving them more velocity. That compelled me to coin this phrase: “The length of the stride is a product of the duration of the ride.”You stride longer by staying connected, keeping your inverted pyramid in the ground and defying gravity with your center of mass until your front foot finally hits the ground.”

Trying to get kids to push off the rubber and create a longer stride is more likely to create a quad-dominant move that throws off the rest of the rotary sequence. This creates a power leak and can have a negative impact on the upper half as well. The pieces of our delivery do not occur in isolation – we are interconnected head to toe when throwing a baseball. If our body can’t create sufficient energy through the lower half, it will seek to find it in other places. This is where poor movement patterns are created.

Key takeaways are pretty simple: Don’t push off the rubber, don’t force a longer stride, and don’t “tall and fall.” Let your big muscles do the work for you – don’t work against them.

5. Stride Straight

A lot of coaches at some point have done drill work where they’ve drawn a straight line out from the athlete’s back foot towards the catcher. The pitcher is then instructed to stride straight so they can land on that line. This is done to keep kids from throwing across their body or falling off to their glove side. Maintaining good direction throughout your delivery is important, but striding straight is not. Don’t believe me? See a couple of guys who don’t stride straight (smh) below.

Some examples of big league All-Stars striding open and closed (from @pitchingninja).

Stepping straight is really a misinterpretation of having good direction to the plate. Direction refers to a pitcher’s ability to generate energy in an efficient sequence towards their target. Having poor direction would be a kid who generates momentum away from their target. An example would be a kid with a pushy/quad-dominant that causes them to step across their body – like Gibson from above (not saying stepping across is bad – just giving an example where it could be bad).

If we’re looking at stride direction, we need to first look at the movements that got them there in the first place. Stride direction is a reaction in the delivery. The movements that occur further up stream (ex: drifting down the mound, using the glutes) are going to dictate how the pitcher strides. Just looking at the stride and saying that someone strides too far open isn’t an effective way to reshape a delivery. It is an effective way to kids get domed up about where their foot lands while also trying to throw strikes and throw the ball hard. There is no freedom or athleticism in this. Instead of letting kids move fast and let it eat, they’re now consciously worried whether or not they’re landing in a straight line. If we want to develop high level moves, we need to let go of striding straight and see the bigger picture. Save the duct tape for problems that actually need it – not problems we create.

Phoenix Rehab Presentation

We were very fortunate to have Monica Johnson, PT, DPT, come in and give a presentation on injury prevention in baseball athletes. She started by sharing some statistics and thoughts on injury rates in baseball today:

- 46% of injured adolescents report being encouraged to play through arm pain

- 36% increased risk of overuse injury in young athletes playing a single sport for more than 9 months out of the year

- Overuse injuries are linked to factors including early sports specialization, skeletal immaturity, year-round playing in games, and lack of adherence to rehab protocol

- Early detection of overuse injuries may be able to prevent further progression of the injury

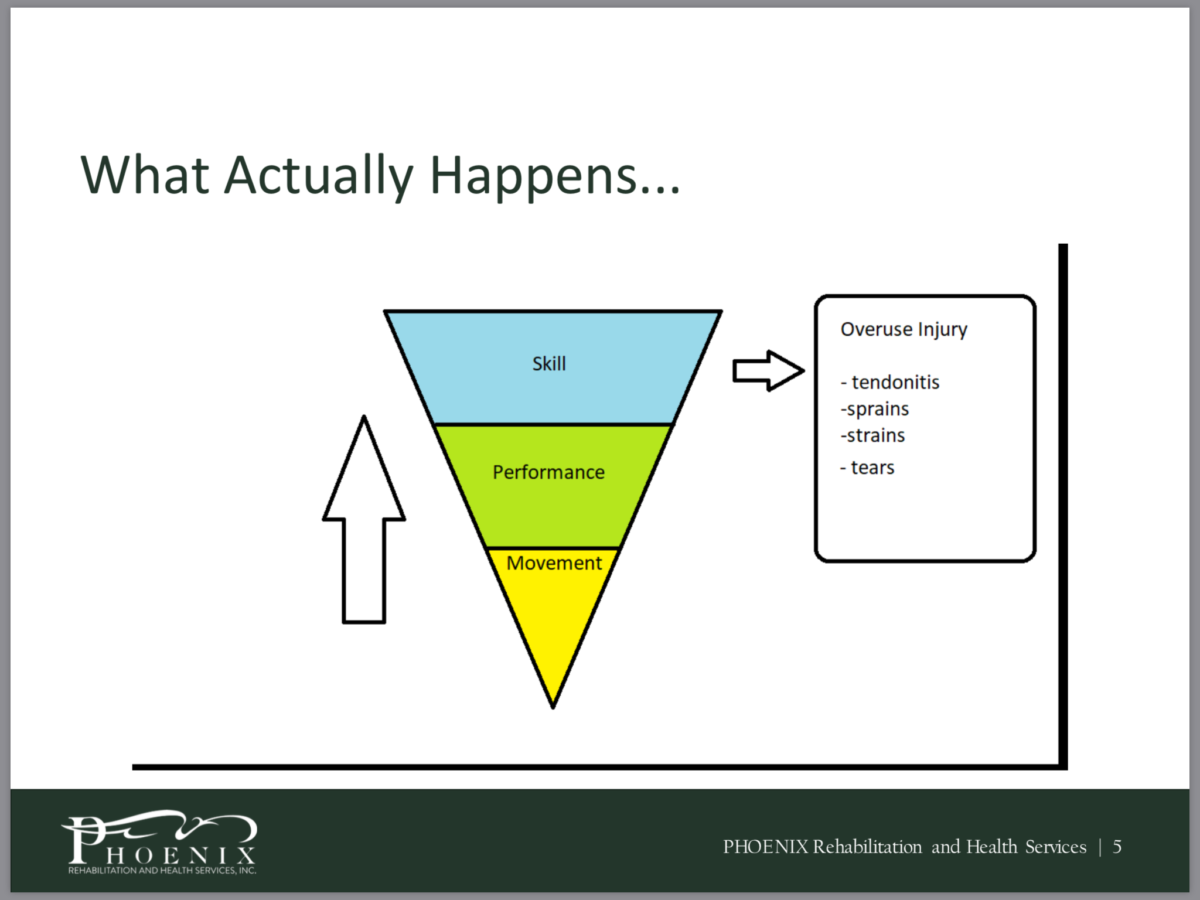

She then illustrated the sad reality when it comes to youth sports training today:

I thought this was one of the most powerful points throughout the entire discussion. Instead of slow cooking young athletes and teaching them movement principles that will enhance their performance on the field, we jump right to the skill portion and spend most of our time there. In essence, we jump right to calculus when kids can’t even grasp basic algebra concepts. If we want to keep kids healthy on and on the playing field, we cannot invert this pyramid. We need to teach kids how to move before we teach them how to play their sport – and moving their thumbs on their sofas doesn’t count.

Before picking up a baseball, kids should be able to execute the five basic movement patterns: hinge, squat, push, pull, and an iso core movement (ex: plank). Because sports require athletes to produce and accept force on one leg, I would add a single leg variation (lunge) to the mix. This is going to help teach kids basic core control and how to use the big muscles in their body. If your kid can’t hinge or squat without collapsing their knees over their toes, there’s a good chance they won’t be able to create a glute dominant pattern from the mound. If your kid can’t keep his scaps from dumping forward while executing a bodyweight push up, don’t be surprised if his elbow hurts while throwing. Mastering basic movement sets the foundation from which you can continue to build on. If you try to outsmart the system and do it backwards, it will catch up to you in time.

If your kid can’t hinge or squat without collapsing their knees over their toes, there’s a good chance they won’t be able to create a glute dominant pattern from the mound.

For more information on how you can start to teach quality movement, see our previous blog posts on building a better warm up and my thoughts from my trip to Cressey Sports Performance. Monica would also be more than willing to help you guys out with anything movement related. She can be reached at mjohnson@phoenixrehab.com or 717.212.9229.

6. Read the watch

Reading the watch refers to when a pitcher shows the ball to second base at front foot strike. If you watch any film of big league guys, you’ll notice virtually no one does this. Instead, the ball is kept in a neutral wrist position. This means that the ball is facing towards third base as a right hander and the ball is facing towards first base as a left hander.

Keeping the ball in a neutral position, images from @pitchingninja and Texas Baseball Ranch

As to why you shouldn’t read the watch, Christian Wonders does a nice job breaking this down. I’ll link to the video here, but below is a quick summary of the points he makes.

- Reading the watch keeps the hand in pronation (thumb down)

- Keeping the ball in a neutral position keeps the hand in slight supination (thumb out)

- The shoulder does not want to get into a clean layback position when it is in pronation. Instead, the humeral head migrates forward and loses congruency in the ball/socket complex.

In its most simplest form, don’t teach kids something that’s not natural. Almost no one shows the ball to second base when they land. It’s not a coincidence, either.

7. Throw over the top

8. Get nice and long/don’t short arm it

Manipulating arm action is one of the most misunderstood concepts when it comes to pitching. Your average youth baseball player is going to hear a barrage of cues when they pick up a baseball that include “Don’t sidearm it, throw over the top!” or “Don’t short arm it, get nice and long!” These cues are usually intended to create “proper mechanics” so kids don’t get hurt when throwing. While they’re well intentioned, they don’t really describe what a lot of high level throwers do. If anything, they’re likely to do more harm than good.

Part of the origination for these cues goes back to the bridge between feel and real. A lot of guys may feel they’re doing certain things when in reality they’re doing the exact opposite. To explain this, check out this clip of Pedro Martinez describing the importance of throwing over the top and compare it to what he actually did below.

Pedro “throwing over the top” (image source)

In reality, arm slot is a little more complex than just thinking “over the top.” A true over the top delivery where the ball is launched from the trajectory of an iron mike does not exist. Your arm slot is dictated by the position of your trunk in space as you rotate to deliver the ball. Your arm should create a perpendicular relationship in regards to the angle of your torso. To better explain this, see the images below.

Kershaw appears to “throw over the top” because he creates more lateral trunk tilt to his glove side. Sale appears to “side arm” the ball (smh) because his torso is more vertical at ball release. If you were to rotate these guys and get their trunks aligned, you would notice the arm slot is identical (the two lines on both pitchers create a perpendicular relationship). If your arm is not able to create this angle in relation to your torso, you are throwing outside of your natural arm slot. This is going to make you more likely to get hurt than not throwing over the top ever will.

Along with this, coaches will try to force a nice and long arm action for pitchers. We have this misunderstanding in baseball where “short arming” (a more direct arm action) the ball is bad and we need to get long in order to throw harder and safer. If you look at some of the best pitchers in the game, you’ll realize that this doesn’t really make sense. If we have guys like Trevor Bauer, Joe Kelly, and Giolito running it into the upper 90s while “short arming” it, why the hell would we teach our kids to get long?

I’m a firm believer that we cannot find an athlete’s unique arm slot or arm action solely through verbal cueing. No two pitchers have ever thrown the ball the same way before in the history of baseball. If we try to figure out an athlete’s own unique style through the use of cookie cutter cueing and drill work, we are more likely to create poor patterns that become very difficult to change when they get older. Our goal as coaches should be to create an environment where an athlete can figure out his own unique style. Teaching kids to “throw over the top” or “not side arm it” won’t help them discover this.

Our arm action is going to take shape through Nikolai Bernstein’s principle of human movement: “The body will organize itself based on the end goal of the activity.” This is why some of the game’s most efficient arm actions come from shortstops and catchers. Players at these positions are forced to make strong throws from different angles (more relevant to shortstops) under considerable time constraints. Because their end goal required quick and fast throws, their arms took on shapes that allowed them to do this. When we’re on the mound, we don’t have these time constraints. Training a kid to just locate his pitches vs. throwing the piss out of the ball is going to create two completely different arm actions.I don’t know about you, but I’m betting on the guy trying to throw fuel.

Trevor Bauer’s advice for what your young pitchers should be doing (from @baueroutage).

If you’re a guy who’s trained your whole life as a pitcher and you feel like a robot when you toe the rubber, you’re better getting off of it and playing shortstop (see tweets above). This is something that Trevor Bauer and Derek Johnson, pitching coach for the Reds, have talked about a lot. Making throws across the diamond from shortstop is going to give you a pretty good feel for their natural arm slot and action. It’s going to unlock some athleticism, create efficient patterns, and get kids thinking externally as opposed to internally. Tucker Frawley, infield coach for the Twins, talked about how pitchers at Yale used to complain about losing a lot of athleticism pretty quickly when they got away from their infield position. If you think about it, their “arm care” program was the throws they made from the infield. When they lost touch with some of the things that probably really helped them out in high school, they started to fall off. If you’re trying to develop a young pitcher, the worst thing you can do is train them like a pitcher. As Bauer says best, get them to move fast, throw hard, and play shortstop.

If you’re trying to develop a young pitcher, the worst thing you can do is train them like a pitcher.

Arm action changes are very difficult to make. If you see someone with an action that looks disconnected or out of sync, start with the lower half. Athletes will tend to find energy in the wrong places if they can’t create it with the big muscles in the lower half. As mentioned before, you can’t isolate the delivery and just look at one piece of it. Observe, see everything that is going on, and then find the things that seem out of sort.

If you’ve checked this box and are still having some issues, below are some ideas you can use to try and create some better patterns:

- Eliminating time

- Any drill that forces the athlete to speed up or get the ball out quicker. A stopwatch is a great tool for this for guys who muscle up and fail to sync up their whole body in the delivery.

- Weighted baseball catch play

- Throwing the football

- Connection balls

- Indian clubs

When it comes to arm action, you can usually do more harm than good. Create the right environment and let the kids do the rest.

9. Get “Extension”

Randy Sullivan of the Florida Baseball Ranch did an awesome job breaking this one down in his ebook book Getting Extension is Fool’s Gold. Below are some of his thoughts on the origin of “getting extension” and why it is a huge velocity/arm health killer.

The idea of teaching pitchers to get “extension” goes back to research in the late 1990s and early 2000s where some very smart coaches figured out the hardest throwers in the game tend to let go of the ball further out in front of their bodies. They calculated that every foot the ball is released closer to the hitter would equal to about 3 mph of perceived velocity. This gives hitters less time to react and can increase the effectiveness of your fastball without actually adding more velocity. Thus, getting “extension” was created as a way to release your pitches closer to the catcher so you could add more perceived velocity. Coaches designed drills like the towel drill where athletes are cued to extend and hit a target on their follow through. The basic idea behind this was right, but the application was horribly wrong.

While we know that high level arms do release the ball closer to home plate, it is not because they’re reaching out to throw the ball closer to home plate. Instead, “extension” is merely the byproduct of an interconnected and efficient delivery. If everything up stream is sequenced correctly, what you’ll see at release is the throwing shoulder will be rotated slightly in front of the glove side shoulder. This is what Ron Wolforth of the Texas Baseball Ranch calls “late launch” and is what the experts deemed as “extension.” The athlete is not reaching out and creating what Randy calls a “linear deceleration pattern.” Instead, they are utilizing a properly sequenced delivery to release the ball further out in front towards the hitter.

Creating a linear deceleration pattern through drills like the towel drill is a velocity and arm health killer.

Creating a linear deceleration pattern is a killer when it comes to velocity, command, and arm health. Sullivan explains that when an athlete creates a linear deceleration pattern through drills like the towel drill, the muscles of the posterior rotator cuff and shoulder disengage after ball release. When this happens, the biceps is left alone to eccentrically resist long axis distraction, humeral head elevation, and terminal elbow extension. In other words, your biceps muscle is working to prevent your arm from flying off your body. This is not a safe way to decelerate your arm as the forces trying to pull your shoulder off exceed 1X your bodyweight. Since your biceps tendon is attached to the labrum, this issue can place a beating on the labrum and eventually pull it right out of the socket.

On top of this, encouraging a linear deceleration pattern can put your elbow at serious risk by preventing the pronator muscles in your forearm from turning on. By getting long and reaching to get extension, athletes are not able to go into shoulder internal rotation and pronation. When the athlete is stuck in supination, the pronator muscles in the forearm are unable to do their job and take the initial stress from the throw. We know that the stress from throwing a baseball (studies show 70-90 nM of stress on the medial elbow at shoulder external rotation) exceeds the stress that the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) can handle (about 35 nM). The forearm pronators play a huge role in the dissipation of this force as they are the first responders to protect the UCL. If this link in the chain becomes broken because of a linear deceleration pattern, the UCL can get overloaded and eventually fail.

For those of you that followed along with all of that, the major takeaways are this:

- Getting “extension” is the natural byproduct of an efficient delivery where the throwing shoulder rotates beyond the glove shoulder at ball release.

- Trying to artificially create extension using the towel drill places the athlete at risk for developing a linear deceleration pattern.

- A linear deceleration pattern causes the forearm pronator muscles and posterior shoulder to surrender to the biceps which rages eccentrically to keep your arm from flying off of its socket.

- A healthy deceleration pattern is created when the hand pronates after release and the throwing shoulder internally rotates. This keeps the forearm pronators and posterior shoulder engaged so they can help dissipate force and let the body naturally unwind.

- The best way to teach a good deceleration pattern is to not screw up kids in the first place.

- Please don’t do towel drills.

While much of this problem is created by human intervention, there are ways you can work and improve your deceleration pattern. Some examples include wrist weights (see more on these here), the Durathro training sock, and overload throwing implements. Kyle Boddy dives into this idea a little more in a Youtube video and an article on fangraphs from a few years ago.

10. Finish in a fielding position

I originally had this linked with the extension part of the presentation, but I wanted to separate it for this article because I didn’t think I covered this enough in the discussion. Pitchers are commonly told to “not fall off” or “finish in a fielding position” after releasing the ball (god forbid you miss a ground ball back up the middle). Both of these cues are well intentioned, but they don’t make sense because 99 percent of big leaguers “fall off.” It isn’t by coincidence, either.

The reason why most big leaguers level “fall off” is because they’re trying to throw the piss out of the ball. It’s a natural byproduct of the body accepting a large amount of force and dissipating it. To throw the ball, the shoulders are going to rotate forward with the throwing arm internally rotating at over 7,000 degrees per second. We also know the lead leg is working unilaterally to accept over 400 pounds of force simultaneously. As a result, your body is going to naturally unwind around your front hip and towards your glove side to accept and dissipate force as efficiently as possible. This causes a lot of guys to “fall off” – a perfectly normal thing to do if you’re trying to throw the ball hard.

Greg Holland, Nathan Eovaldi, and Chris Davenski all run it up into the upper 90s without finishing in a “fielding position” (from @pitchingninja).

If we know that slamming on the brakes isn’t great for our cars, why would we want to slam on the brakes with our arm?

When we encourage pitchers to finish in a fielding position, we are cutting off their ability to naturally decelerate. Athletes are not able to completely rotate around their front hip and create late launch to help the arm safely unwind. Cutting off forward shoulder rotation encourages early launch where the athlete’s arm is brought to an abrupt stop after release. This results in significant banging and recoiling of the anterior shoulder and can create shoulder and elbow pain in throwers. If we know slamming on the brakes isn’t great for our cars, why would we want to slam on the brakes with our arm? Your body also isn’t going to produce a lot of force if it can’t safely and efficiently accept it. There’s no reason for your body to punch the gas if it doesn’t trust the brakes system.

Does this mean that finishing in a fielding position is always bad? Absolutely not. There are guys who throw the ball very well that finish in more of a fielding position. However, this is unique to their own style. They more than likely did not have coaches who were constantly berating them for falling off the mound. They simply found the best way for them to produce and accept force. Forcing athletes into a pattern that does not fit their unique mold is called cookie cutter coaching. We know that cookie cutter programs do not work because no two athletes are ever the same. Teaching everyone the same way will mirror a bell curve: Some will get better, the majority will stay the same, and some will get worse.

As a coach, the key takeaways should be pretty simple: “Falling off” is not a bad thing, it is a good thing. Your kids are finding ways to move fast, throw hard, and naturally decelerate their body. Each kid is going to have their own unique finish after they throw the ball. Be very careful when you start to tamper with how they finish after they throw. If you tamper with the body’s natural brake mechanism, you’re more likely to place athletes at risk for injury.

Please stop telling kids to finish in a fielding position. You’re likely doing more harm than good.

11. Death by Verbal Cueing

The overuse of verbal cueing might be the greatest detriment you can use when trying to build pitchers that thrive in competitive environments. This is something I’ve talked about in the past on here and I still feel the same way about it. With all the mechanical stuff that we can screw up, the absolute worst thing we can do for kids is to dome them up with a million different cues in practice. If you think about some of the best performances you’ve ever had, most will agree that they were instinctual. We weren’t worried about where our hand was or whether we were using our legs enough. Instead, we trusted in our training and thought less. We were simply in the moment and competing with everything we had in the absence of thought.

Research has shown the most effective focus of attention for game performance is a specific, external focus. An external focus refers to when we are focusing on something outside of our body in our environment. Examples of external cues include “throw it through the mitt,” “hit it over the center field wall,” and “try to separate the floor.” Unfortunately, most of the cueing used in coaching promotes an internal focus. An internal focus refers to when we are focused on something within our body. Examples of internal cues include “use your legs more,” “get your hands up,” and “don’t drop your elbow.” The broader the cue is, the more room there is for misinterpretation.

Instead of keeping things simple and letting their athleticism take over under the lights, we jump in and complicate things through poor cueing.

If we are constantly thinking about what our body is doing in games, we are becoming our own worst enemy. We’re not trusting in our training and we’re not giving ourselves the freedom to compete one pitch at a time. Instead, we’re worried about the aesthetics of our delivery. We want every single move to be perfect even though we know there are going to be a multitude of factors that impact our delivery every single game (energy levels, field conditions, weather, nutrition/hydration, sleep, soreness, etc.). Instead of focusing on executing pitches and competing with what you have that day, we’re worried about whether we’re using our legs enough or whether we’re sidearming (smh) the ball or not. This is where we create kids that can’t get out of their own head. Instead of keeping things simple and letting their athleticism take over under the lights, we jump in and complicate things through poor cueing.

The double-edged sword to internal cueing is that there is a time and place for it early on in the skill acquisition process. It is helpful to give kids a better feel for the difference between certain moves by creating an internal focus of attention (conscious incompetence). However, the focus must eventually progress to external (unconscious competence) as the athlete develops mastery over the skill. If they cannot execute the skill with a specific, external focus of attention, it will not play in a game environment.

Derek Johnson likes to describe this process of building a skill using “over the rubber” and “over the plate.” When we are over the rubber, we’re working on developing a skill. This could be trying to create a better movement pattern, shape to a breaking pitch, or velocity. When we’re over the rubber, we’re not worried about executing pitches. We’re trying to create feel for something that’s going to eventually help us in a game environment. When we’re over the plate, we’re in a competitive, game-like mindset where the main focus is executing pitches. We’re not focused internally on our delivery – we’re focused externally on competing with what we have to send guys back to the dugout.

If the focus is on executing pitches, you can’t cue guys to use their legs more. If the focus is on building a better movement pattern, you can’t worry about filling up the strike zone. We’re either over the rubber or over the plate – we can’t do both.

As coaches, we must not blur the line between over the rubber and over the plate. If Jonny is trying to create a better pattern with his lower half, the execution of his pitches is going to be slightly off. If you berate him for not filling up the zone while focused internally on his lower half, he’s going to abandon the new pattern and go to the old one that is more comfortable for him. Your sessions should not be a mix of over the rubber and over the plate. Create a goal for the day and coach it accordingly. If the focus is on executing pitches, you can’t cue guys to use their legs more. If the focus is on building a better movement pattern, you can’t worry about filling up the strike zone. We’re either over the rubber or over the plate – we can’t do both.

When it comes to cueing, less is usually more. Yogi Berra said it best: “You can’t think and hit at the same time.” Pitching is no different.

Part 2 of the article will go over items 12-24