Last year, Lucas Giolito had a dream season for the Chicago White Sox. After sputtering to a 10-13 record in 2018 and posting a 6.13 ERA in 173.1 IP, Giolito exploded in ’19 en route to his first All-Star appearance. He punched out 228 batters in 176.2 IP for a 11.62 K/9 – 5th in the MLB (and nearly double the 6.5 K/9 he posted in 2018).

Lucas Giolito, 8 consecutive Ks. 😯 pic.twitter.com/n4vVHLMoss

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) September 12, 2019

He solidified himself as a staple in the White Sox rotation winning 14 games, limiting his free passes to just 2.9 BB/9, and finishing with a career-best 3.41 ERA – almost cutting his ERA in half from a season ago. He finished sixth in the Cy Young award voting and his 5.1 WAR (according to Fangraphs) was good for 10th in the MLB. To put that into perspective, he totalled -0.2 WAR in his first three seasons in the bigs.

While Giolito’s resurgence and impressive stat line definitely caught the attention of the baseball world, what was most interesting about his 2019 season was how he did it. A lot of people expected Giolito to eventually ascend into one of the league’s premier starters ever since he graced the MLB top prospects list, but they weren’t exactly expecting him to look like this when he did:

For reference, this is what he looked like in 2018:

Let’s look at them side by side:

If you couldn’t tell, Giolito made some pretty significant changes prior to the 2019 season. After struggling in 2018, Giolito connected with his old high school pitching coach and came up with a plan to overhaul his delivery. Among the things they incorporated included a weighted baseball program to on ramp into throwing and work with the Core Velocity Belt. The combination of the two helped Giolito simplify his delivery by learning how to hinge better, use his glutes to control his move down the mound, stay closed longer, and tighten up his arm action so he could get into better positions more consistently.

These changes had a significant impact on Giolito’s data. In 2018, Giolito’s four seam fastball averaged a mere 92.4 mph, spun at 2099 RPM, got whiffs just 14.3% of the time, and hitters generated a wOBA of .412 against it. In 2019, Giolito’s four-seamer averaged a career-high 94.4 mph, spun at 2333 RPM, generated whiffs 26% of the time, and hitters accumulated just a .278 wOBA against the pitch – a .134 improvement from just one season ago. To put that into perspective, hitters accumulated a .250 wOBA against Jacob deGrom in 2019 – good for 22nd in the MLB. If you added .134 to his wOBA against, he would have finished tied for 351st.

Giolito’s four-seamer wasn’t the only thing that improved, either. His new delivery helped kill about 100 RPM (1651 to 1563) off his change up and turned it into his main put away pitch as he increased his whiff% on it from 34.8% to 41.3%. He also added 0.7 mph to his slider, shaved off 4.6 inches of vertical movement, and increased his whiff% on the pitch from 36.3% to 42.0%.

In a matter of one offseason, Giolito ended up transforming himself from a fringe big-leaguer into one of baseball’s most electric young arms. His new delivery unlocked a completely improved arsenal which propelled him to the best season of his career. It’s a great example of the power of player development and how moving to and through better positions can have a significant impact on the data produced which can have career-changing implications.

He might have also caught the attention of Robbie Ray.

Over the past five reasons, Robbie Ray has played an integral role in the Arizona Diamondbacks starting rotation. However, he hasn’t quite been the most consistent part about it. It’s no secret why, either – Ray struggles filling up the zone consistently. In 2019, the Marlins were the worst team in baseball when it came to handing out free passes averaging 3.83 BB/9. Robbie Ray handed out 4.34. The best part?

It was an improvement from the 5.09 he handed out in 2018.

Ray’s notorious command issues have been something that has really held back the left-hander throughout the course of his career. In fact, you could probably make the argument that Ray should be one of the top pitchers in the league. The last three seasons, Ray has posted a K/9 mark north of 12 and has surrendered 7.7 H/9 or less. Below is a list of all of the pitchers in Major League Baseball who did that in just last year:

- Justin Verlander (12.1 K/9, 5.5 H/9)

- Max Scherzer (12.7 K/9, 7.5 H/9)

- Gerrit Cole (13.8 K/9, 6.0 H/9)

That’s it. Oh, and Ray’s 12.13 K/9 was also good for the 14th highest mark in MLB history. His 12.11 K/9 from 2017 ranks 16th all-time.

Robbie Ray has the makings to be one of the best pitchers in Major League Baseball, but he’ll only be a shell of what he could be if he continues to hand out four free passes every nine innings. The stuff is there, the whiffs are there, and we saw in 2017 what he’s capable of when he puts it all together. He just hasn’t found it since.

This past offseason, Ray decided he needed to make some changes if he wanted to put his walk problems behind him and return to All-Star form. One of those was a dairy-free diet. Ray showed up to camp this year 15 pounds lighter and in much better physical condition than the previous few seasons. This could play a significant role in his ability to go deeper into games and execute pitches later in his outings when under greater amounts of fatigue. In 2019, Ray went 7 innings in just one of his 33 starts. While the walks certainly played a role in this, a cleaned up diet could have a pretty big impact on his ability to be effective later in his outings.

The other thing he did was change up his delivery. Below is a side-by-side comparison that was featured on the MLB Network of his windup from 2019 and what he looks like now in 2020:

For Ray, inspiration for his new delivery started back when he was teammates with Zack Greinke in Arizona. He said:

“It seems like (Greinke’s) dancing on the mound, the way he’s deliberate with everything, and so I just wanted to have a little bit of that feel of a dancing move… I didn’t ask him why he did it. I was just kind of telling him that I liked his delivery because it just seemed so fluid.”

Fluid is a word Ray has used in the past as a goal for what he likes to feel in his delivery. Below is an excerpt from 2018 where he talked about some of the mechanical changes he was trying to make coming off an oblique injury in April (more on this later):

“During my leg-lift, my hands weren’t coming to where I could separate and have a nice round delivery where my arm is coming through really fluid. So that was the biggest thing is my hands were kind of stuck low and I was stabbing more than having a nice fluid motion.”

When Ray started to experiment with taking his hands over his head this past offseason, he felt the fluidity he was looking for. He said, “For me, going over the head, it allows me to have that feeling of not getting stuck in my delivery like I used to, but also have some fluidity to it.”

The change in arm action was a conscious change inspired by Ray in an effort to try and solve his notorious command issues. In an interview on MLB.com, Ray explained how he thought his arm used to be too long and it was preventing him from getting into good positions consistently. After observing some guys around the league who have had success shortening up their arm action – Giolito being one of these guys – he decided to try it out for himself.

Going into this season, Ray liked the changes – but he didn’t really talk about the arm. He said, “I’m not losing stuff arm side because my direction is more towards the plate. I’m not pulling so much with my front side, which is allowing me to stay in the zone and not pull and leave stuff arm side.”

So now here’s where things get interesting. Despite Ray’s conscious attempt to overhaul his delivery and solve his problem with handing out free passes, it hasn’t really seemed to help. In fact, you could make the argument that based on what we’ve seen from his first two starts, his command has gotten significantly worse. Let me make this clear: I get it. It’s only been two starts and we’re going through one of the most unique seasons in MLB history. It’s possible that Ray just might need some more time to get used to the changes so he can feel more comfortable with them. However, let’s take a look at the numbers and see if you still feel the same way.

So far in 2020, Ray has relied heavily on his four-seamer throwing it 52.4% of the time (like Giolito, he also scrapped his sinker this past offseason). On paper, it’s a much better pitch. It’s averaging 94.0 mph – a 1.6 mph increase from last season and his hardest since 2017 – it’s spinning at a career-high 2469 RPM, it has 3 more inches of horizontal movement, and it’s getting whiffs 28.1% of the time – on pace for a career-high.

It’s also landing in the zone just 40% of the time – a 12.7% decrease from 2019. When it is landing in the zone, it’s typically in a hitter’s count and it’s getting tattooed for a .474 slugging mark. This is a significant increase from his .313 xSLUG for the pitch (his four-seam xSLUG last year was .408). Like I said, on paper it is better – it just doesn’t play particularly well when you’re more likely to flip heads on a coin than you are to throw a strike with it.

If we look at his arsenal as a whole, Ray is throwing strikes at just a 52.9% clip – a significant decrease from his career-low of 61.7% in 2018. He’s throwing first pitch strikes just 41.9% of the time (59.3% last year), he’s getting to 0-2 just 14% of the time (29.6% last year), one out of every ten batters is getting to a 3-0 count, and three of those hitters have reached base via four pitch walk. Ray handed out 11 of those in 751 plate appearances in 2019. He’s only faced 43 batters so far this year.

In Ray’s last outing, he handed out six free passes in 4.1 IP – something he didn’t do all of last season. I understand that the sample size is small, but it just isn’t plausible to write off numbers like these as an issue of not having enough innings under your belt. Whatever Robbie Ray changed this past offseason so far is not working. If he continues at this pace, it’s not only going to be a long season for Ray – it’s going to be a really long offseason (speaking of guys who might have a long offseason).

So where exactly did things go wrong?

Let’s start by looking at Ray from 2017 – his best statistical season to date. In 28 starts, Ray went 15-5 striking out 218 in 162 IP. He set career marks in ERA (2.89), FIP (3.72), WHIP (1.154), H/9 (6.4), and was selected to his first and only All-Star team. This is what he looked like:

We’ve got some pretty good stuff going on here. Out of leg lift, Ray is able to hinge and use the big muscles that surround his pelvis (i.e. glutes, hamstrings) to control his move down the mound. His pelvis and trunk stay closed, his arm gets up at foot strike (where his front hip starts to accept force – not just when the front foot touches), it catches and unwinds around the trunk pretty nicely, and he’s able to stop, get joint centration in his lead hip, and get across with pretty good direction towards home.

The one thing Ray didn’t really go a great job of in 2017 is hold on to the ground with his back foot. In fact, he comes out of the ground so early and so much that his back foot is nearly airborne before his front foot even gets a chance to land:

This is something we don’t really see when we look at some of the best arms in the game – especially guys who have had a ton of success filling up the strike zone. Curt Schilling, Dan Quisenberry, and Bob Tewksbury (left to right) all pitched 12+ seasons in the big leagues and finished with a career BB/9 under 2.0. Their back foot looks a little different than Ray’s just before they get into landing:

We’ll get into this more later, but for now we know that guys who lose the ground early tend to have issues creating stability for the pelvis which can cause it to fly open too soon, drag the torso into early trunk rotation (ETR), and leave the arm behind to play catch up.

If we look at Ray prior to his injury stint in April of 2018, this is exactly what we see:

If we compare him side by side at landing to what he looked like a season ago, we notice a huge difference – especially with his trunk and arm:

Instead of staying closed, Ray flies open in ’18 which forces him into ETR and puts him in a really bad position to throw his punch. This took a pretty significant toll on his obliques because he wasn’t able to land in a position of stability where he could align his joints optimally so they could accept and disperse force evenly throughout the system (i.e. joint centration). When one part of the chain can’t do its job, another part has to pick up the extra slack. Because Ray was no longer able to get to a good landing position, he ended up doing a lot of yanking as opposed to rotating and his obliques had to pay the price for it.

While Ray definitely felt the added stress in his trunk, he also probably felt it in his arm. Flying open gave his arm less time, space, and freedom to get up on time and into a good position at landing. Instead of getting up on time, Ray’s arm was showing up late to the party which was probably creating the “stabbing” sensations he talked about above. He knew he wanted to try and create something that felt more fluid so he decided to play around with his hand positioning and rhythm during his IL stint.

Let’s go back to what Ray looked like from his first start back from injury in ’18:

Here’s where we can start putting together some theories on the changes from this past offseason. Ray was absolutely right that something was off in his delivery that was impacting how his arm felt, but his interventions to try and fix it were not effective because they weren’t addressing the source of his problems. He was still losing the ground early, flying open, and now he probably made things worse because he added more movement with his arm that needed to sync up with the rest of his body. He knew he needed to feel fluid, but he didn’t know what he needed to do in order to create that feel consistently and effectively.

As a result, his delivery didn’t improve, the results didn’t improve, and his arm ended up getting worse. His elbow was scooping up, carrying too far, and everything was getting yanked towards the third base dugout. It’s no surprise 2018 was his worst statistical year for handing out free passes; when the arm gets worse, everything else gets worse.

In 2019, Ray probably realized he added too much to the equation in ’18 and make a conscious decision to simplify things to get back to All-Star form. It was definitely an improvement, but it wasn’t quite consistent across the board. He still didn’t hold the ground very well with his back leg and his direction started to shift towards the third base dugout because he couldn’t stabilize and create joint-centration as well on the front side:

This showed up in the data as the majority of the misses with his four-seamer and slider were pulled wide to his gloveside:

It’s quite the contrast from what his pitch distribution looked like in his best season in 2017 – not nearly as many glove side misses:

Now let’s go back to Ray’s thoughts from above. Something he talked about coming off his delivery overhaul this past offseason was how he wasn’t missing arm side with his stuff anymore. He thought his direction was a lot better and made a point to mention how he wasn’t yanking off pitches nearly as much.

Let’s see if the data validates this:

He’s definitely not yanking stuff the way he was last season, but he’s missing quite a bit high and arm side. If anything, he’s probably missing high and arm side more than he ever has in his career. Just look at the video from above – the pitch is in the zone, but the glove was set up on the outside part of the plate. While this pitch missed its spot and still landed in the zone, a lot of Ray’s stuff this year hasn’t been so fortunate.

Before we dive into why this is happening, let’s start with what we know. This season, Ray has shifted where he starts on the rubber to the middle as opposed to the first base side, he’s using a smaller rocker step, taking his hands over his head, and he’s getting to a position at leg lift where he has more counter rotation of the pelvis, trunk, and he has more tilt with his shoulders:

When Ray gets into landing, we notice how he lands with much less posture this season despite starting with more at leg lift. He also lands much more open this year as opposed to last year:

At release, we notice how Ray is using a much lower slot this year due to the postural changes we’ve talked about above. Where the trunk goes, the arm is going to follow – well hopefully, at least:

When we get Ray to his max point of tension post release, we start to see some of the directional stuff he was talking about. This season, Ray looks a lot closer to what he looked like in 2017 and it’s definitely an improvement from what he was doing last year. His cross-body is more towards home as opposed to towards the third base dugout:

Now let’s circle back to the buzz about the changes with the arm. When I first watched the MLB segment where Al Leiter broke down Ray’s arm action changes this season, I had a couple of different thoughts. For one, I didn’t think the arm was the biggest change about Ray in the first place. I thought the differences in posture, landing position, and cross-body tension were all more significant changes than how he simply the took the ball out of his glove. We place a lot of emphasis on the arm – as we should – but we have to remember without inside information it can be tough to tell if the arm was a conscious change or a subconscious byproduct of a different movement pattern down the chain or an adaptation to a specific constraint. Lucas Giolito wasn’t necessarily trying to create a shorter arm action; he just kind of picked it up through a better lower half and a weighted baseball program.

When I figured out the arm action changes were a deliberate change and I saw what happened in his first two starts, I came to a second thought: Tinkering with the arm probably wasn’t necessary.

Going to a shorter arm action has definitely started to become a trend in baseball just the way we’ve seen more guys scrap their sinkers and go to high heater/breaking ball combos. However, trends are cyclical and they don’t optimize for the individual. Getting shorter might be the attractive thing to do as of late, but making positive arm action changes isn’t as simple as just getting shorter. There’s a lot more to it.

The issues Ray was having with command weren’t probably due to a “long” arm action, but there might have been some other things going on that could have made it feel long to him. In order to get to the bottom of this, let’s dive into arm action a little bit deeper so we can have a better understanding of what is and isn’t optimal.

At 108 Performance, we look at a couple of big rocks when determining if someone has an efficient arm action or not:

- Arm is up at foot strike

There are a couple of things to keep in mind when looking at whether the arm is up or not at foot strike. For one, we don’t just view foot strike as when the front foot lands. Foot strike is when the lead hip starts to accept force. There are some guys who may have a flat arm when their front foot first hits, but it eventually gets up once their front hip starts to accept force. This isn’t optimal, but it is a way for certain athletes to buy time so they can get their arm up when it’s time to rotate. It’s something we actually see with Ray, as well. In some of his better clips, his arm isn’t up when his front foot hits but it gets up by the time he’s ready to throw his punch.

As for positioning of the arm, we want to see the humerus at a 90 degree relationship to the torso where the elbow is in line with the throwing shoulder. When the elbow climbs above 90, the humerus migrates superiorly in the socket and creates an impingement where the cuff can’t stabilize and keep the ball flush in the socket. When the elbow lands below 90 degrees, it has to scoop up to get into the plane of rotation and ends up creating a similar impingement in the shoulder.

When we look at the angle of the forearm to humerus, we want to see something around a 90 degree relationship. Notice the key word around – the forearm does not need to be exactly at 90 or inside 90 degrees to throw a baseball healthy, hard, and with precision. This is the part Al Leiter didn’t quite get right in his analysis of Ray and it’s something a lot of people probably don’t realize. Some guys like Giolito need to get tighter in order for their arm to work efficiently, but there are guys out there who either can’t or don’t need to get inside 90 to have success. In fact, below is an example of a two-time MLB All-Star who doesn’t quite get inside 90 with his forearm:

Instead of getting to a certain angle with the forearm, it’s a lot more important that the arm catches and matches plane of rotation – our next big rock:

- Arm catches trunk and matches plane of rotation

When we look at hitters, we want to see the middle and the barrel rotate together in order to make efficient moves to the ball. This concept is very similar to the arm catching the trunk. When we’re ready to rotate and our lead leg starts to accept force, we want our arm to be up so it can “catch” the trunk and rotate together with it. For this to happen, we need to have all of the slack in our arm pulled out at foot strike so when we start to rotate our arm is ready to come with it. If the arm isn’t up and slack hasn’t been pulled out, it’s going to have to get pulled out pretty quickly so it can catch up to the trunk. If we know it’s not a great idea to punch the gas on a boat with a raft tied to it where the rope hasn’t been pulled taught, it probably isn’t a great idea to do the same thing with your arm.

As the arm catches the trunk, we want to see it rotate around the shoulders and through the plane of rotation. This gives us the ability to transfer the most amount of force with the least amount of stress by using the most efficient path (i.e. geodesic). While some throwers utilize different postures and angles with their trunk, all of the best ones work around this same plane with the arm to deliver the baseball. In essence, everyone throws from a low slot – some just do it with trunk tilt.

Now let’s think about why Ray might not be having so much success with his newer and shorter arm action. When Ray’s hands break, he takes the ball back towards his ear almost as if he’s trying to pull back an arrow. This action ends up pulling out all of the slack in his arm before he gets into foot strike. This is not ideal – when we create tension is just as important as actually creating any tension at all. As a result, his arm gets stuck in an inverted-W type of position where it has no freedom or space to capture the trunk.

This is why we’re seeing a ton of high and arm side misses – there’s a mismatch between the translation of energy and the rotation to deliver it. The chain is pulled tight before Ray has a chance to throw his punch from deep. Throwing requires a constant balance between understanding when to turn things on and when to turn things off – also known as surround inhibition. In Ray’s case, he’s creating too much tension in his arm too soon which prevents him from catching the trunk deep and causes his elbow to scoop up, carry forward, and leave the plane of rotation. This is what’s creating misses like these:

Here’s what it looks like slowed down:

Notice how the arm doesn’t catch the trunk deep like Scherzer of Vasquez from above. The elbow scoops up, carries too far beyond his trunk, and turns into more of a pushing motion than a punch. For reference, this is what Ray looked like in 2017:

His arm action might be “longer” in this clip, but it’s a lot better than what he’s doing today. Instead of getting it tight and creating a ton of tension early, Ray is able to stay loose longer which allows his arm to catch his trunk, get up in time, and work around the plane of rotation in tangent with his middle. His arm has the freedom, time, and space to pull this off because he’s able to stay closed longer into landing. Remember how we mentioned how he’s landing more open this year? This becomes a pretty important detail because it’s a lot tougher for your arm to move to and through good positions when either 1) the pelvis is opening up and limiting the amount of space you have down below or 2) the trunk is getting peeled to the glove side before you have a chance to throw your punch. The arm was never the source of the problem; rather, it was a source of feedback telling Ray that there was a problem.

I get that Ray didn’t just change his arm action this past offseason and some of the changes he made were potentially beneficial, but he probably didn’t need to change his arm at all. He just needed to learn how to create more stability down low so he could stay closed longer and give his arm space to work to and through better positions.

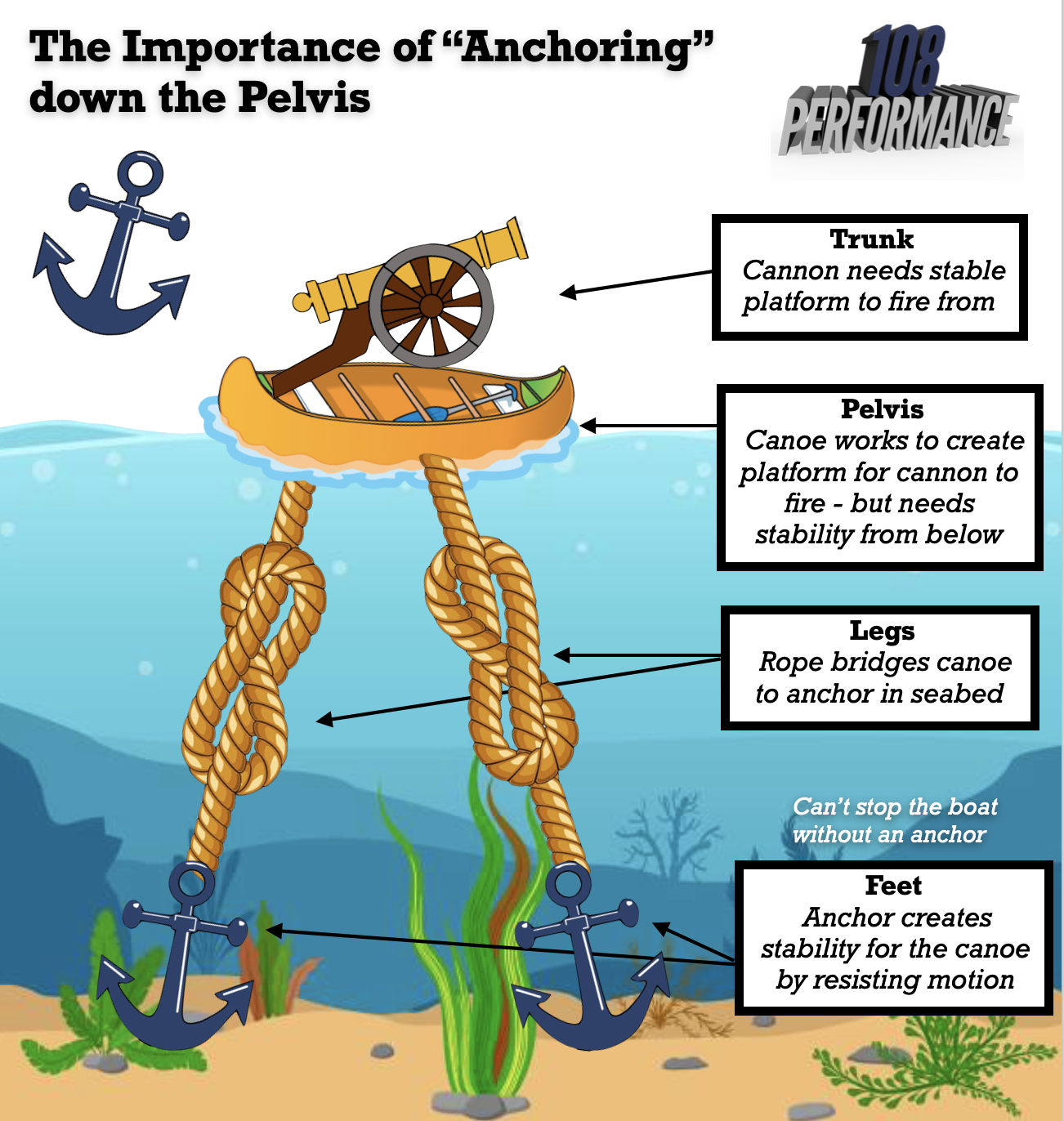

In other words, he needed to learn how to hold the ground better. To explain this, check out this visual below:

The feet play a critical role in the pitching delivery because they serve as the anchor points for our pelvis so it can stabilize and allow the upper half to mobilize around it. If we go back to Ray, he’s losing his anchor point with the back foot before he even has a chance to throw his punch. If we can’t anchor with the back leg as the center of mass moves down the mound, it becomes really difficult for our pelvis to create a stable and repeatable platform for rotation. This would explain a lot of the inconsistencies we’ve seen with Ray over the years. While we’ve seen him dominate and have a lot of success in the past, he hasn’t been able to recreate it as much as he’d like because he’s constantly fighting for stability. When the pattern lacks stability, it becomes really difficult to repeat it and produce force with precision – i.e. where the command issues are potentially coming from.

I think Ray has figured some things out about his delivery and his body that could absolutely be positive changes for him going forward, but I don’t think shortening up his arm was what he needed to start filling up the zone more consistently. It’s ultimately going to be up to him to figure out what is best for him and his career, but I think what we’ve seen so far in two starts is not a great sign that things are trending upward. Giolito might be an example of how shortening up the arm can lead to an increase in performance, but Ray is currently an example of how shortening the arm doesn’t always yield the best results – especially when the arm probably wasn’t the problem in the first place.

Command artists come in all sorts of sizes, shapes, deliveries, and arm actions. Short is one of them, but it is not all of them:

On a final thought, something Eugene and Will talk about a lot at 108 is how not everyone needs to get long, but everyone needs to get short. We’ve already established that getting to or inside 90 at foot strike is not necessary, but the allowable bandwidth for this position is not monstrous. There is a moment in time where all throwers need to get “short” with their arm so it can catch and match the plane of rotation, but just getting to that position isn’t as important as how we move to and through it. Ray’s thought of needing to get shorter may not have been wrong, but his interpretation of how he needed to get there wasn’t optimal. Arm action isn’t about getting long or getting short – it’s about getting to positions of leverage so you can throw your best punch.

If Ray wants to become the pitcher he knows he’s capable of becoming, he’s got to learn how to stop punching himself, first.