The following article is a joint piece where I am joined by Ben Reed to describe Marcell Ozuna’s recent struggles and inability to secure a multi-year contract in free agency. Ben is currently a student-athlete on the varsity baseball team at Oberlin College and is aspiring to work in advanced scouting or baseball operations in Major League Baseball.

Ben:

When Marcell Ozuna hit the free agent market last winter, many people expected him to command a sizable multi-year deal. MLB Trade Rumors ranked him as the 11th best free agent and predicted he would land a 3 year, $45 million dollar pact with the San Francisco Giants. Similarly, FanGraphs ranked him as their seventh best free agent and tabbed him to receive a 4 year, $66.6 million dollar pact. MLB Trade Rumors listed seven teams who would make sense as a free agent destination for Ozuna in that price range. While answering a questionnaire for a major league team last winter, I was tasked with evaluating Ozuna as he entered the open market.

I wrote the following:

“Marcell Ozuna (29 years old) enters free agency after averaging 2.7 fWAR over two seasons with the Cardinals. His offensive numbers (107 wRC+ in 2018 and 110 in 2019) failed to replicate the success he enjoyed during 2014 (4.5fWAR) and 2017 (5.0 fWAR). However, Ozuna’s Statcast batted ball profile (92nd, 93rd, 97th percentile in xWOBA, avg. exit velocity and HHB%) showed he’s among the game’s top hitters. Ozuna walked at a career-high 11.2% clip in 2019 while also suffering from a .259 BABIP – well short of his career .315 BABIP mark. Defensively, FanGraphs’ DRS and UZR rank his outfield play as slightly above average, while Statcast is much harsher on his defensive play (-2, 3, -1 and -8 OAA totals over the last four years). Ozuna’s range doesn’t figure to improve as he ages and his arm remains a liability. I would project a 3-4 year/$15-17 million AAV deal for Ozuna. A team willing to swallow the draft pick compensation attached to him should enjoy multiple years of 2.5-3.5 fWAR production at a reasonable price.”

Yet, when the dust settled on free agency Ozuna was left with a one year, $18 million dollar deal with the Atlanta Braves. So how did myself and two other reputable baseball websites whiff so badly on Ozuna’s value as a free agent? To properly answer that question, we must take a look at why Ozuna’s Statcast batted ball profile doesn’t match up with his actual production.

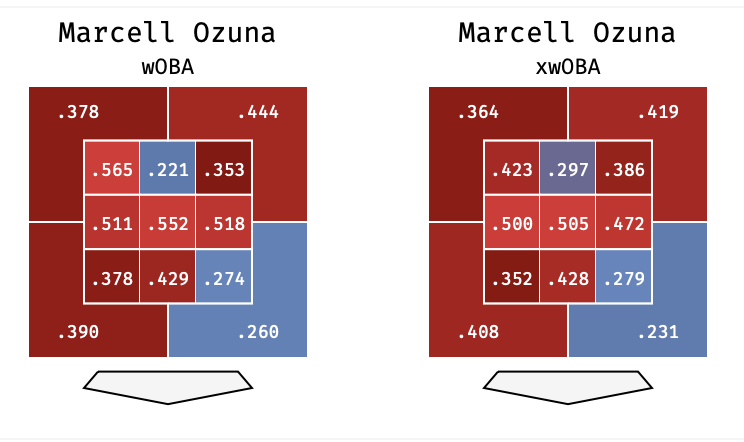

In 2015, 2016, 2018 and 2019, Ozuna’s xWOBA outweighed his WOBA. This was especially pronounced in both ‘18 and ‘19. In fact, Ozuna had the greatest difference between his xWOBA and his WOBA out of all 250 qualified major league hitters in ’19 (-0.046) and the 15th greatest difference among all 249 qualified hitters in ’18 (-0.032). To provide a point of reference, the MLB average for this statistic is right around 0; 0.001 to be exact. If Ozuna could have matched his xwOBA of .381, he would have finished in some elite company behind NL Rookie of the Year Pete Alonso (0.384), Aaron Judge (0.382), and would have actually outperformed Trevor Story (0.380), Mookie Betts (.380), and Jose Altuve (.374). Story, Betts, and Altuve were all All-Stars in 2019.

While some people may attribute one season of underperformance to bad luck, two seasons definitely raises some red flags. Considering the company Ozuna could have finished with in 2019, I decided to do some further investigating and figure out exactly what was causing the lack of performance that we were seeing.

When I first started to come up with theories about why Ozuna was falling short of his expected performance, my first instinct was to explore whether Ozuna was falling victim to the shift. In 2017, Ozuna was only shifted on 3.7% of his plate appearances. This number increased to 8.0% in 2018 and up to 12.3% in 2019. Yet, the increased shifts did nothing to curb Ozuna’s offensive performance. In 2018, he had a .374 wOBA and in 2019 a .390 wOBA in the plate appearances where he was shifted against. Both of these figures were notably higher than the figures he put up in non-shift plate appearances. Simply, there was no evidence to suggest the increased shifts were doing much of anything to create the notable difference between his xWOBA and WOBA numbers.

Without any answers, I took to watching Ozuna’s batted balls to see if I could find anything that might stick out. Ozuna has somewhat of an unorthodox swing that jumps out as unusual to the naked eye. While watching some of the flyballs and line drives that he hit, I realized a pattern. I watched numerous batted balls that exhibited a 100+ mph bat exit velocity paired with a mid 20 degree launch angle that seemed to die well short of its expected landing distance. Each time it seemed as if the fielder had to drift, turn, or readjust his route to the right. This is where I started to come up with a theory that just might explain why we were all way off on our predictions for Ozuna this past offseason.

Me:

In order to get to the bottom of Ozuna’s lack of performance, let’s start by checking out a ball he hit from this past September. The ball came off the bat at 100.4 mph and at a 24.1 degree launch angle. If we look at data from Baseball Savant on the 2019 MLB season, baseballs hit 100 mph and at a 24 degree launch angle have just under a 70 percent chance they’ll find some green, a 62.4 percent chance they’ll go for extra bases, and a 33 percent chance they’ll find some seats. Hitters batted .694 on them – a significant increase from the MLB average on BABIP (.298) – and accumulated a wOBA of 1.131. To put it very simply, Ozuna’s chances of reaching base on this batted baseball were very high. Given the part of the park this was heading for, his odds at touching all four bases were pretty high as well if you couldn’t tell from his reaction off the bat.

Now let’s take a look at where it ended up. Ozuna thought it was gone, Cubs pitcher David Phelps thought it was gone, and the St. Louis crowd sure thought it was gone – but it turns out everyone was wrong. Instead of clearing the fence, Ozuna’s blast landed 6 feet short of the 375′ sign and ended up in the glove of right fielder Tony Kemp – probably at his surprise.

So let’s talk about the first reason why I brought up this clip. If we reference back to the data, it paints a pretty clear picture that this ball probably should have landed somewhere that wasn’t a glove. Instead, it found a glove. It’s a great reminder that even the best players can seemingly do everything right and still not get the desired outcome they were looking for. Luck – as Ben referenced to above – plays a role in baseball that’s much larger than what we would like to admit. This was one of those times where Ozuna just got plain unlucky. Data tells us that balls hit at 100 mph and at a 24 degree launch angle end up as hits 70 percent of the time, but baseball doesn’t reward us for simply hitting the ball hard and on a specific trajectory. It rewards us for hitting the ball where the defense isn’t.

When players present with differences between their wOBA and xwOBA – good or bad – the first plausible explanation is simply luck. There are situations like the ones above where Ozuna could have hit a frozen rope right at somebody and got nothing for it. These kinds of outs could definitely skew Ozuna’s data and make it seem as if he was underperforming when in reality he was just pissing on balls and getting unlucky. However, it is unreasonable to blame Ozuna’s disappointing 2019 season on “bad luck.” Luck is a factor in performance – not a predictor of it. If Ozuna overperformed his xwOBA in 2017 by 0.016, it is unlikely he underperformed by -0.046 in 2019 because he was smashing mirrors and walking under ladders. Chance does not explain a 0.062 point swing in wOBA over the course of two years, but a swing issue definitely could.

This takes us to the second reason why I used the clip from above: Ozuna had an issue slicing baseballs in 2019. Ben was spot on when he noticed a slice in Ozuna’s batted balls and they are definitely impacting his data – or lack of, in this case. If we go back to the play from above, we notice how Kemp had to make a last second to his route right around the warning track to account for the slice on Ozuna’s ball. While every good hitter is going to fillet a ball once in a while, it seemed to be a theme for Ozuna in ’19. It’s a hair tough to see from the broadcast view, but pay close attention to where the ball comes off the bat, the route the outfielder takes, and how much the ball does or doesn’t carry (links to the full videos are in the captions):

We know that xwOBA is determined by using exit velocity and launch angle to figure out what the likely outcome for the batted ball is based on about how far it should travel. We also know that one thing xwOBA neglects is batted ball spin. While exit velocity and launch angle can give us a pretty good feel for where the ball should end up, where it actually ends up can really be thrown off based on the spin of the ball – especially if there is a significant amount of sidespin.

This is something Zach Gifford dove into in a recent article where he documented Ozuna’s 2018 and 2019 struggles. In the article, he broke down an uncharacteristic cluster of warning track fly balls in the right center field gap. These balls were coming off the bat over 100 mph and at about a 33.5 degree launch angle, but were only traveling at an average distance of 365 feet. In 2019, the MLB average for balls hit at this speed and this trajectory was 379 feet – an 11 foot increase. While this is only one cluster of batted balls, it shows just how big of a deal Ozuna’s sidespin is and can start to explain a more plausible theory on why he’s been underperforming. Data tells us how balls hit at a certain speed and specific trajectory should perform, but it couldn’t quite predict how Ozuna actually performed because it didn’t account for his problem with sidespin.

The important thing about this is the data wasn’t wrong – Ozuna should have been doing more damage. The ball in the first video should not have landed in the glove of Tony Kemp. It should have landed in the Cardinals bullpen. These kinds of swings are the ones that arguably cost Ozuna a ton of money this past offseason. If we really want to pinpoint why he didn’t get the deal we all thought he was going to, we’re going to have to take a closer look at the swing and see exactly what’s creating the data that kept teams from pulling out their checkbooks.

If we look at Ozuna’s swing into landing, there are a couple of things we notice right off the bat that could be contributing to his lack of performance:

At landing, we want to see guys in an athletic position where their weight is equally distributed, they’re centered over their belly button, their pelvis is closed, and they have some sort of posture over the plate. Now let’s take a look at Ozuna and see where he gets to when his front foot lands:

Not so good.

Instead of spreading apart, staying centered, and landing in a position of balance with posture, Ozuna reaches with his front leg and leaves the majority of his weight on his back leg. As a result, his pelvis gets put in a position where it’s stuck and can’t hold on to tension any longer. It has no other option but to fly open like a gate which puts Ozuna in a really bad position at landing. At this point, his swing is screwed: He’s not centered, his weight is stuck on his backside, his pelvis is open, and he has no posture over the plate. If we wouldn’t want to throw a punch from this position, we definitely wouldn’t want to hit a baseball from this position.

Instead, we’d want to do something closer to this:

This is what Trout, Altuve, and Sosa all look like paused at landing:

These guys don’t get stuck on their backside and fly open – they stay closed, centered, and ultimately put themselves in a position where they can deliver their mass into the strike. It’s a big difference from what see with Ozuna and it can start to give our theories some visual substance:

So now let’s take a look at how this is impacting his path to the ball. As referenced above, the reason why Ozuna’s pelvis flies open is because it gets stuck and can’t hold on to tension anymore. When our pelvis gets stuck and flies open, we lose a ton of space that is critical to the swing. The best way to visualize space is to think about the area from the top of your torso down to our feet. When our pelvis flies open, it impedes on this space and leaves us with less room to work. The less space we have, the less room our barrel has to capture energy and make efficient moves to the ball.

To compensate for the space he doesn’t have, Ozuna ends up pinning his hands against his body to try and maintain direction without getting peeled off to the pull side. This ends up creating a longer arc to the ball and adds time to the swing that Ozuna can’t really afford. The more time our barrel needs to get into the zone, the less likely we are to catch the ball out in front like Arenado below:

The deeper we catch the ball towards the catcher, the more likely we are to impart unintended sidespin at contact. This is where Ozuna’s slices are coming from. He’s not able to deliver his bat head into contact and catch the ball out front because his barrel is stuck and doesn’t have the freedom to make efficient moves to the ball (it’s tough to have any kind of space or freedom when our hands are pinned against our torso). This happens because he moves to and through positions that aren’t advantageous for force transmission, space, or direction. As a result, he ends up struggling on pitches middle-in and up where there is a greater time constraint to catch the ball out in front:

When he isn’t getting blown up on middle-in heaters in or filleting balls to the opposite field, he simply isn’t swinging. Ozuna’s increased walk rate (5.6% in 2018 to 11.2% in 2019) might make some believe he’s maturing and improving his plate discipline, but a sudden increase in walks can actually be a red flag depending on the hitter and context. In Ozuna’s case, it probably isn’t a good sign. While his overall chase rate has decreased 3% over the past two years, his in zone swing percentage has decreased from 72.4% in 2017 to 68% in 2019. This gives us a feel that something could be wrong. It’s one thing to to swing less at pitches outside the strike zone – it’s another to swing less at pitches inside the strike zone. Considering this and the lack of performance that sparked our investigation, it’s more probable that Ozuna’s increased walk rate is because of what we’re seeing with his bat path.

If we go back to the swing itself, we know Ozuna doesn’t have a ton of space to operate in. Because of this, there’s a good chance he doesn’t think he has the time he needs to get his barrel into the zone. The less space we have, the less time we have to operate. If we’re not able to get into a good position where we can pull the trigger with confidence, we’re probably going to swing less – hence, more takes and potentially more walks. While Ozuna’s overall chase rate has improved over the past few years, it is unlikely his career-high walk rate in 2019 was solely an indication of improved plate discipline. Walking more is not bad, but walking more and producing less is not good.

When Ozuna is pulling the trigger, he’s not doing so hot on pitches that aren’t straight:

In 2019, Ozuna was dreadful against breaking balls batting a career-low .149, slugging .341, and totaling a wOBA of .227. Given what we know about his swing, this shouldn’t be much of a surprise. He’s not able to get to a good position at landing which prevents him from getting to his front side, holding his line, and creating adjustability out front – all really important things when it comes to hitting stuff that spins. Adjustability is less about letting the ball get deep and more about going to get it out in front. If we’re not able to get to a good landing position so we can work into our front side, hold our line, and catch the ball out in front, it becomes really difficult to do stuff like this:

So now let’s take a look at Ozuna from his 2017 All-Star campaign and see if we see any similarities or differences:

Yeah, big difference. This ball didn’t get filleted into a dead zone on the warning track of the right-center field gap. It left the yard. To get a feel for just how different this swing is from the one we first looked at, check out the visual below:

Without even looking at the rest of the swing, this position and how Ozuna gets to it gives you a ton of information about his swing. If we look at the one from ’17, we basically see the opposite of what he did in ’19: He stays centered, his pelvis stays closed, he maintains space, and he starts to work down and into his front side so he can leverage his ability to put force in the ground and lay his mass into the strike. He can’t do this on the right because he’s stuck and getting peeled out of the ground by the time his barrel is actually ready to make moves to the ball.

When Ozuna gets to a good position at landing, it becomes a lot easier for him to make efficient moves with his barrel. Instead of getting pinned and stuck, his hands now have the space and freedom to get away from him and make efficient moves to the ball. This increases his chances for making hard quality contact out in front and decreases his chances for slices.

Remember the issues he was having in 2019 with pitches middle up and in? Yeah, he didn’t have those issues in 2017. When we don’t have to fight for space, we don’t have to worry about whether we’ll have enough time or not to pull the trigger. This made it a lot easier for Ozuna to cut the corner and get his bat head out in front of baseballs on the inner half of the plate.

He also didn’t struggle nearly as much with breaking balls. When we get to a good landing position with stability, we have the ability to work down and into our front side, hold our line through rotation, and make adjustments out in front. In 2017, Ozuna batted .285 and slugged .554 against breaking balls.

In 2019, he slugged 0.552 on fastballs.

It’s kind of weird how you tend to hit better when you’re moving to and through good positions more consistently. It’s almost like he should do it a lot more often – especially considering he ranks in the 93rdpercentile of the league in exit velocity, the 96th percentile in hard hit percentage, the 92nd percentile in xwOBA, and the 91st percentile in xSLG. Marcell Ozuna has the potential to be one of the best hitters in the game, but teams don’t write checks based on a player’s potential – they pay guys who perform.

But if he does perform, it brings up the question that we all failed to answer correctly this past offseason: What is Ozuna really worth?

Ben:

The answer to this, as you could probably expect, just got a lot tougher considering the implications of a 60 game season. For guys in contract years, there are still a lot of question marks at the moment that make it very difficult to predict what teams are going to be willing to spend on free agents this offseason. The 102 games that won’t be played and the fans that won’t fill the seats are going to make a serious dent in the pockets of MLB clubs. It’s not only going to be really tough to score a big contract this offseason – it’s going to be really tough to make a convincing case in just 60 games.

We know that Ozuna is going to be turning 30 years old this November, he doesn’t have a great arm, and he’s not a great overall option in the outfield. With the MLB seemingly getting closer to a universal DH, Ozuna’s saving grace is going to be his bat. If he does what he did this past season again in 2020, it’s unlikely he’s going to get a deal that’s a lot better than the one he got this season. Teams will pay for the bat, but they’re not going to pay for guys who take more pitches in the strike zone and fillet balls that should be driven over the fence. Ozuna’s 2019 campaign did show some encouraging pop (29 homers were a career second-best), but his overall production across the board just wasn’t enough for teams to pull the trigger on a multi-year deal. His decision to take a bet on himself in 2020 and score a bigger contract for 2021 might have backfired due to circumstances he couldn’t control, but it doesn’t mean he can’t change his fortune by getting his swing back to a better place.

Ozuna will again enter free agency at conclusion of this season searching for a new home. Depending on what he puts together this year, he’ll be faced with a couple of different scenarios this offseason. If he struggles and an organization with a strong player development system figures out what we’ve just shared, they might end up closing a deal on an elite hitter at a discounted price.

If Ozuna fixes his slice and shows shades of 2017, he just might score the contract we all thought he should have gotten a year ago.