What we miss when we focus on still shots

“If someone hands you a picture and shows you a picture and says “here’s their stance,” “here’s their negative move,” “here’s contact,” – If you give them any advice on what they’re doing wrong, you are taking such a gamble because you have no idea how they got to those positions.” – Dr. Greg Rose, from Elite Development Baseball Podcast

When I first got into coaching, I knew I had to build a better understanding for what a good swing or delivery looked like. To do this, I tried to simplify the complexity of a swing or delivery by breaking it down into a series of still shots. I collected and sorted these shots based on critical moments in time that I believed were important. For example, the categories I used for hitters were stance, move out of balance, foot plant, initial move to the ball, contact, extension, and finish. For pitchers I liked to look at their move out of balance (leg lift), glute load/move down the mound, foot plant, ball release, deceleration, and “finishing in a fielding position” (it’s in quotes for a reason).

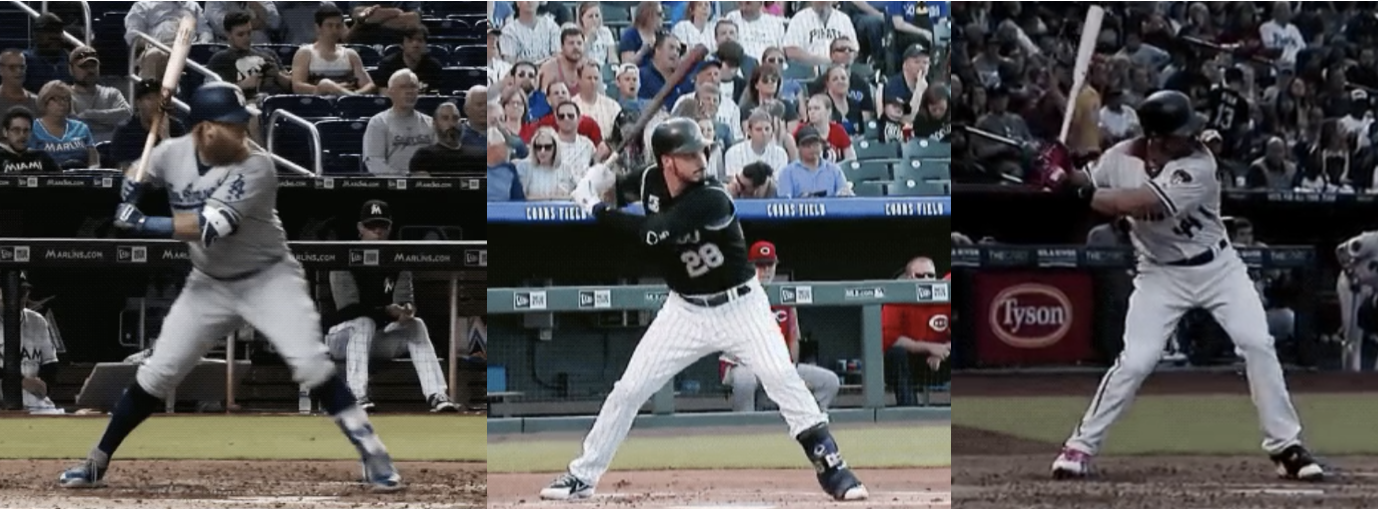

When I started to collect still shots from a lot of different players, I started to see see where guys had similarities and where they presented with slight variations. For example, I noticed how a lot of hitters at foot plant tended to be in a 50/50 position where their feet were spread outside of their shoulders, both heels were in the ground, their head was over their center of mass, and their hands were back behind their belly button. All of them landed in an athletic position where they had equal bend in the knees, some degree of posture (chest over the plate), and their glutes sat behind their heels. As for differences, some guys had different hand positions (lower vs. higher, father back vs. more out front), bases (wider vs. shorter), and some landed a little more closed (Stanton) or open (Khris Davis). This was important for me early on because it helped give me a feel for things to look for and things not to get over obsessed with. If I knew certain positions had more variation, I didn’t really coach those as much directly. I tried to get the big rocks in line (i.e. posture, balance) before figuring out how the other pieces came into play.

While these still shots helped increase my understanding of the swing or throw, they didn’t tell the entire story. To explain this, let’s think about why balance points become popular. If we look at these snapshots of Justin Verlander from behind and in front, it would appear that he is in a position of balance where he’s keeping his center of mass over his rear leg.

Now let’s take a look at how he gets to the position. Let’s look at Verlander from the side.

Here’s what he looks like specifically into peak leg lift:

If we look at how Justin Verlander moves to this position of “balance,” we notice a totally different move than what the snap shots might initially suggest. Notice how his center of mass never stays over his rear leg and he never gets to a true balanced position where he is creating zero lateral movement. Instead, he starts to drift down the mound slightly as he gets to his peak leg lift. If we just look at the picture of him at leg lift, we miss out on the fact that how he got to that position is totally different than the perception of the initial still shots.

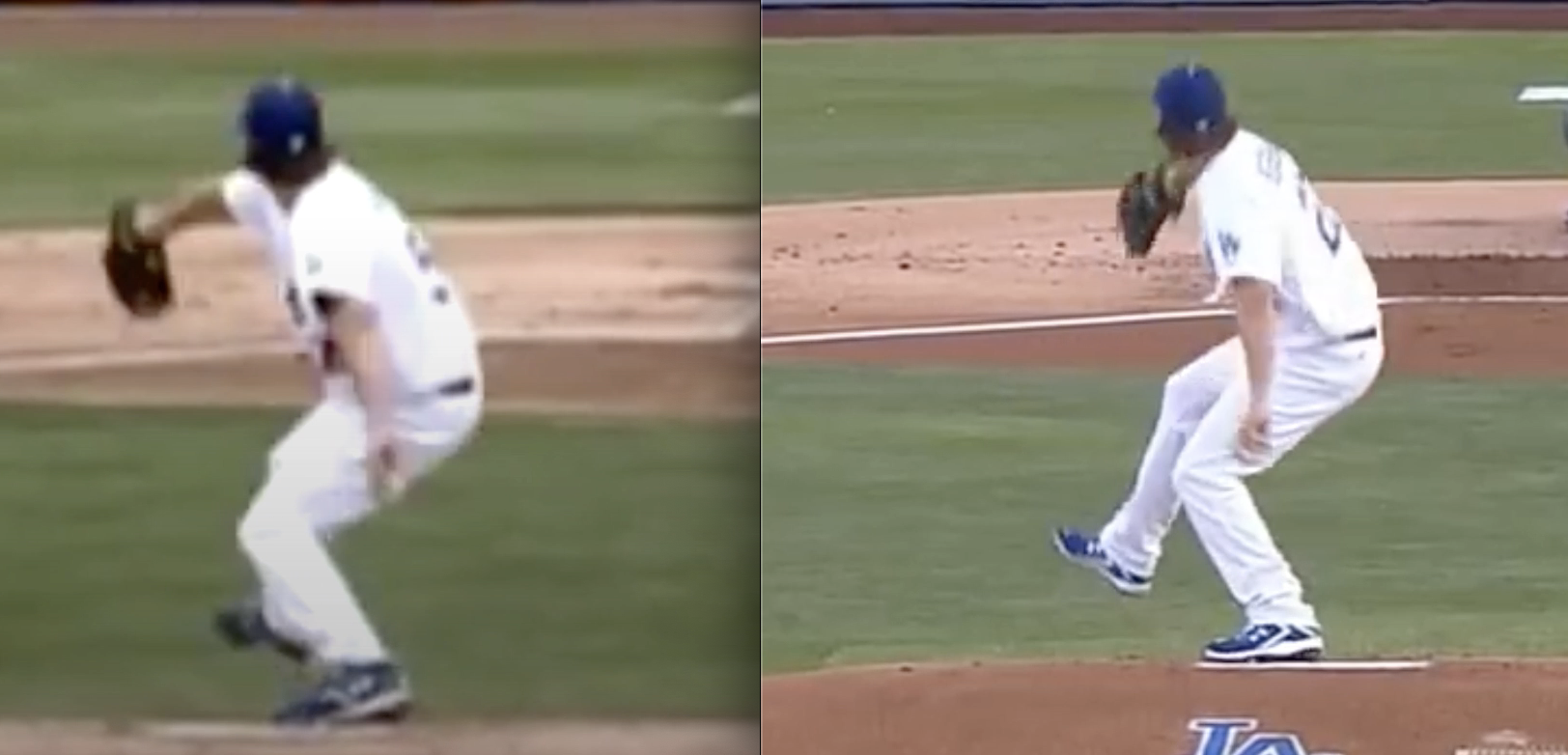

Now let’s look at a different scenario. Below are two still shots of Kershaw side by side at two different points of his career. The shots are taken as Kershaw starts to move down the mound after peak leg lift.

To the untrained eye, these two pictures from two different moments in time look pretty similar. However, they’re not as similar as you think. Let’s look at the movements side by side.

Now the differences become much more clear. If we look at the delivery on the left, we notice Kershaw shifts his weight towards the front part of his foot after leg lift and comes out of the ground early. This video was taken from Kershaw’s rookie year in 2008. If we look at the video on the right, we notice a completely different sequence. Instead of shifting towards the front part of his foot, Kershaw stays into his glutes longer, keeps his back foot connected to the ground for a longer period of time, and creates a more efficient sequence with his lower half. This video was taken from Kershaw’s perfect game in 2014. Kershaw had issues with giving up free passes his first few years in the league walking 4.33/9 in 2008. He didn’t have this problem in 2014 – he walked 1.4/9. While there are plenty of other factors to take into the equation, more efficient moves definitely played a role in his improved command of the strike zone.

When we look beyond the pictures and look at the movement that created them, we create the context we need to make accurate decisions on what that player needs. If we look at the pictures without looking at the movement, we’re forced to assume how they got to those positions. Two guys can get to the picture-perfect contact position, but it doesn’t mean they took the same route to get there. If you just check a box based on how they look at contact, you’re neglecting the one thing that matters: How they got there.

Pictures can be a great way to slow things down and bring awareness to certain parts of the movement, but they can’t paint the whole story. If we wouldn’t judge a book by its cover, we definitely shouldn’t judge a player based on a snap shot in time. Good moves play; good pictures don’t always play.

Communication is Connection

I was able to sit in on an awesome zoom conversation last weekend that featured some of the best hitting minds in the game which included Bobby Tewskbary, Andy McKay, Jerry Weinstein, Don Wakamatsu, Darin Everson, and Rick Strickland. The conversation dug into the weeds of player development and tackled different types of problems that we all face when coaching hitters. Out of all the things I learned throughout the five hour conversation, there was one reoccurring theme that really stuck out to me – and it didn’t involve the swing.

When Wakamatsu worked in pro ball with Brian Butterfield, current third base coach for the Angels, one of the things he picked up on was how Brian placed a premium on building relationships. In spring training, Butterfield took the time to get to know each one of his players on a personal level. He figured out where they were from, what high school they went to, previous coaches they had, information about their family, and their interests outside of baseball. He always tried to find something they had in common so he could use that as a tool to connect and strike up a future conversation. By placing a premium on his communication with his players, Brian increased his ability to influence them because they knew he cared about them. Ken Ravizza said it best when he said, “Your players won’t care about what you know until they know you care.”

Ken Crenshaw – Director of Sports Medicine and Performance for the Arizona Diamondbacks – talked about this on a more tactical level saying, “There are plenty of people that can talk but can’t connect. If you didn’t connect with that guy on the “why,” it’s going to be harder for them to make that change.”

If we break this down in a baseball context, let’s think about the process of making a swing change. As a coach, just telling the player what they need to do is not enough – you need to start with a shared understanding of where that athlete is in that moment of time. There’s a really good chance you aren’t the first coach that has worked with that hitter. Because of this, you need to do some homework before you start teaching. This includes how they’ve trained in the past, what’s worked for them, what hasn’t worked, injuries they’ve had, what problems they’re currently trying to solve, and what aspirations they have for the future. You need to understand their perception of a good swing, their swing, and what they need to feel to get their best swing off. You can’t change perception of the model if you don’t know what the model looks like in the first place.

When you’ve got all the pieces you need, you can use the pieces you already have and combine them to start putting together the entire puzzle. Any gaps in understanding will create a hole in your finished product. The more holes you have, the tougher it is going to be to build buy in. If players don’t believe in what you’re doing you don’t have a chance to create any sort of significant changes. Our goal should be to put together the entire picture – not just the part of the puzzle we want to drive home.

When you can create this shared understanding, it’s important to maintain an open line of communication throughout the swing design process. Some things you say or do will work, others won’t, and some might work if the athlete better understood what you were trying to say. You need to uncover these gaps in understanding by asking a lot of questions, seeking real time feedback, and adjusting on the fly based on what they’re comprehending or missing. We can’t just assume our players know what we’re talking about it. If they can’t explain it in their words and describe how it relates to their swing, they don’t understand it well enough.

When you think about “staying closed,” you might think about your pelvis while someone else thinks about their trunk or hands. Your perception of staying anchored could help you stay connected to the ground longer while others may actually get out of the ground sooner because they don’t operate well when focused on the extremities. If you’re trying to drill home a point and the player can’t understand exactly what you’re trying to communicate, you’re not going to get the results you want – and it’s not the player’s fault. If the communication channels aren’t crystal clear, you only have yourself to blame. We connect when we communicate; we lose connection when we lose communication. If you don’t make it a priority, your message won’t get any further than your perception of it.