Reverse Engineering from the Skill

Assessments are something I’ve been interested in for a while because of the role they play in designing individualized training programs. Being able to individualize is a critical skill as a coach because your players are akin to snowflakes; not one is ever going to be the same. Being able to give them exactly what they need at that moment of time is an art. Each kid is going to need different thoughts, feelings, cues, drills, and actionable strategies molded into a unified plan that is constantly changing based on their needs. Step one to building this plan begins with a thorough assessment of where they’re currently at, what problems they’re trying to solve, and what’s preventing them from getting to where they want to be.

A good assessment is like an interrogation process; you’re constantly observing, asking questions, and inquiring to find information you need to make accurate decisions about what they are currently going through. If you’re interrogating someone, there is no such thing as a stone left unturned; assessments should be no different. If there is something that is preventing that athlete from becoming the best version of themselves on the diamond, you need to find out about it. You will always be at the constraint of what you don’t know. A thorough assessment makes sure there is nothing you need to know that you don’t.

The recent push in baseball to individualize has helped create some awesome strategies and tools to help build a better understanding of what problems athletes are having and why. High speed video, 3D motion capture systems, movement screening, Rapsodo/Yakkertech, Hittrax, KVest, and force plates have all given us the ability to improve our understanding of exactly where that athlete is at that moment of time. The process of swinging a bat or throwing a pitch has not changed – we’ve just eliminated guess work when it comes to breaking it down. When we eliminate guessing, we improve our ability to make accurate decisions that help us individualize our coaching. Guessing and checking may seem like a good algebra strategy until you’re through your 10th guess and you still don’t have an answer – or, better yet, a plan. When we assess, we skip guess and check and get right to the meat of it. Time is the most precious resource we have. Assessing may seem like a lot of time early on, but having the discipline to do it the right way will save you the extra time and head scratching later down the road. There’s a reason why Abe Lincoln spent four of his five hours sharpening the axe before actually cutting down the tree.

Out of all the tools introduced for assessments, the one I became really interested in was movement screening. When I heard that your ability to swing or throw was at the constraint of the limitations of your body, I became really interested because I wondered what kind of impact they could have had on my playing career. I’ve personally since been through the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) and I thought it provided a lot of valuable information, but it wasn’t quite it. I knew understanding the body was something that needed to be taken into account when building an individualized training program, but I also knew passing the FMS shoulder mobility test with flying colors actually meant you were more susceptible to injury. New assessments like TPI and OnBaseU peaked my interest but I needed to know more about them before I decided to dive in and get certified.

When I read through Old School vs. New School and learned about Eugene’s thoughts when it came to physical “limitations” (he prefers the word “adaptations”), I had a feeling he was on to something. When he explained to me at the ABCA that using these “limitations” to your advantage was a much easier – and potentially more effective – way to coach, I knew I had to look at movement screens through a different lens. If Eugene had done research and found a large majority of “hip mobility programs” actually increased your chances of getting hurt, what does the role of movement screening actually play? If some of the best sprinters in the world (maybe the best rotators in the world) all have tight hips, ankles, hamstrings, lower backs, and flat feet, that’s the point in assessing for mobility in these areas? Are movement screens driving the right kind of interventions or are they inspiring counterproductive work?

If we think about the role of movement screens in the assessment process, we need to understand that all they are is information. What we do with that information is what is most important. If we want to leverage that information for effective interventions, we need to look at it within the context of the skill. The skill is not only the most important part about the assessment process; it is the assessment. The athletes that come to us are not concerned about whether their hips are too tight or whether they don’t have enough dorsiflexion in their right ankle – they just want to get better at baseball. Understanding how they’re physically structured can help give you information on how to help them get better, but it must be used within the context of the skill. If you don’t understand the why behind the screen, you lose your ability to make accurate decisions because you become so lost in the details that you forget the most important things: The swing or the throw.

If you can thoroughly and accurately define what the skill looks like, what it should look like, and how to bridge that gap, the new and flashy tools become a slave to the person who should be driving the intervention: The coach. If you don’t understand the skill, you become a slave to the data; and that never ends well. The assessment then turns into a crap shoot where you collect a bunch of data, get lost searching for something that might correlate, and maybe throw some shit at the wall to show off your “expertise.” If you don’t treat the skill as the assessment, you get lost chasing information trying to find something that matters. If you know what matters in the skill you know what data you need to collect, how to collect it, and how to communicate it to so you can help that player improve. Movement screens create awareness for where that athlete is starting, but it is not the mold.

When the skill is not where it needs to be, it can create the illusion that something physically is off and needs to be changed. This is where the movement screens can come into play – but not necessarily for the right reasons. Zach Dechant, head strength coach at TCU, described a situation on a recent zoom call with Eugene where he was working with an athlete that showed below average shoulder maximum external rotation (MER) throughout his delivery on their motion capture system. If execution of the skill is not taken into context, this can drive some unnecessary (and time consuming) interventions. In this case, just looking at poor MER and not understanding how it was created will make you falsely think there is some sort of constraint preventing them from creating MER. In this case – along with many others – the athlete did not need more MER. They had plenty of it; they just didn’t know how to unlock it in their delivery. When Zach made a few tweaks to the delivery, he unlocked another 10-15 degrees within a matter of a couple throws. He didn’t need mobility work to open up his shoulder; he just need to teach the kid how to tap into what he already had.

The important thing to understand from this is the data was not wrong; the athlete did need to improve his MER. How you unlock this MER is where the importance of good coaching comes into play. Movement screens provide you with really valuable information; how you use that information is far more valuable. Just looking at someone’s IR deficit in their rear hip is not only stupid (you don’t really need it), it’s neglecting the main thing: The skill. Measuring it doesn’t necessarily mean that you need to change it – you just need to know how it affects the movement. Getting stuck on your backside because you have no IR is a problem, but just getting the athlete to toe out (think like a squat) is a much simpler solution than giving the athlete a mobility program they probably don’t need in the first place.

By the way, how much mobility do elite rotary athletes really need in the first place?

The Mobility Myth – Why we probably don’t need as much as what we think

Before I get ostracized for this one, let’s pull out the common sense card and start with what we know about baseball. We know that a swing or throw requires the creation and dissipation of force in a small window of time. We know that players are competing in narrow windows of time where they don’t have the affordance to gradually create energy; they’ve got to get off their best punch without getting knocked on their ass. Yes I know pitching isn’t reactionary, but I also know you can’t get a 20 foot running head start before throwing a pitch. By deductive reasoning, success in baseball is largely going to depend on your ability to create the most amount of force (rate of force development) within the smallest window of time.

Now let’s get away from the baseball thing and say you’re jumping on a trampoline. If you wanted to create the most amount of air using the least amount of time, what would you want those springs to look like? How taught would you want the jumping mat? Would you want springs that were looser or more tightly bound? Would you want a lot of give or not a lot of give when you landed on the mat? I don’t know about you, but I would want tightly bound springs and I’d want the jumping mat pulled as taught as possible without becoming rigid. If I’m trying to get as high as I can in the least amount of time, I don’t want a lot of slack in the trampoline; I want to redirect energy as quickly and efficiently as possible. The guys who we think “lack mobility” are just like the best sprinters in the world; they have the tightest springs. The guys who have plenty of mobility have much looser springs. Just because the springs are looser doesn’t mean you can’t create the same/more air time, but at what time cost does it come at? If the fittest of a species is able to do the most with the least, are guys with looser springs maximizing their ability to do this? Are guys with tighter springs better suited for this?

Now let’s revisit the baseball thing: Are you sure your guys need more mobility, or do they just need a better movement solution so they make can better use of their current mobility?

One of Eugene’s favorite one liners is, “Things become a thing when we do the opposite.” When strength and conditioning started to become popular in baseball, a lot of experts noticed how tightly bound some of the best players in the game were. The initial response to this was to try and open them up so they can increase the window in which they can produce force and prevent them from developing injuries. While it was well intentioned, the performance results were not uniform across the board; some guys got better, many saw no change at all, and plenty others got worse or hurt. Mobility programs became a thing when we did the opposite of what we were observing in the field – a lot of really tight guys. The questions then becomes this: Were some of the best players tight by accident or by design? When in doubt, I try to use logic. Logic would tell us the best players in the game are probably really good for a reason. In other words, they probably didn’t have tight hips for the hell of it.

The game of baseball hasn’t really changed that much. We still like guys who throw the ball hard, hit it far, and run fast. Players who are really good at these are some of the tightest, twitchiest guys on the planet. They don’t use a whole lot of mobility because they probably don’t need it for elite rate of force development. This is part of the reason why strength training took such a long time to gain traction in baseball – some of the best players were already naturally tight and didn’t like the feeling of adding muscle mass and getting even tighter. Their springs were already tightly bound enough; throwing a blanket strength training program into the mix probably didn’t help the cause.

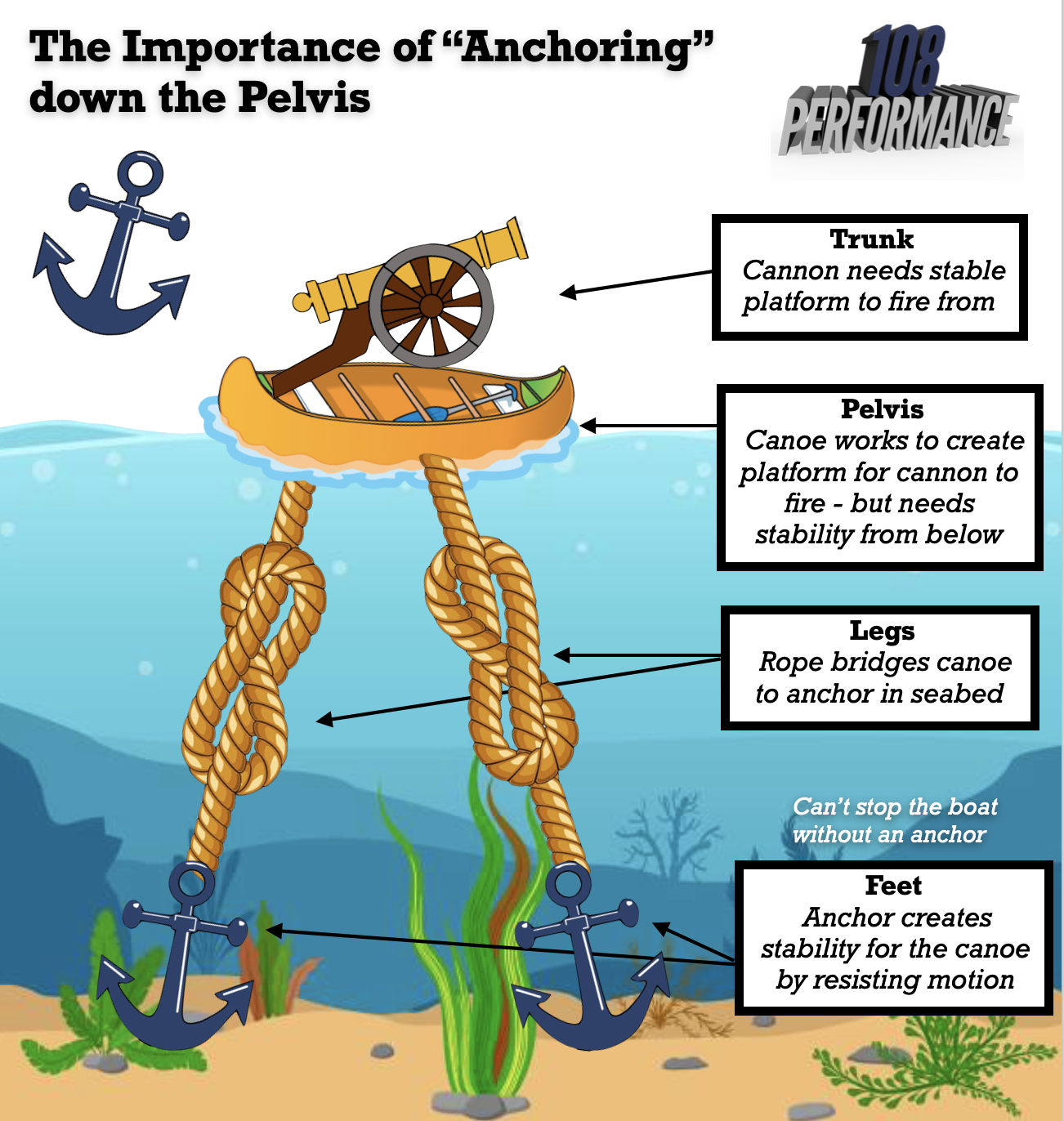

I do think that opening up some guys can be a good idea in certain cases, but I also know opening up ranges of motion without assessing the individual can add slack that the system doesn’t really need in the first place. This is not a great strategy for long term health and performance. We know that the spine doesn’t like aggressive rotation in the first place. Why would we want to open up the lower extremities so we can rotate over a greater arc? What do we think happens to the raft when we add 30 feet of slack to the rope and have the boat take off at full speed? Did guys develop tighter hips because it was a more beneficial movement solution hat allowed them to produce the most amount of force without placing their body in compromised positions? Did executing the skill under a time constraint influence this? I don’t know about you, but I think these all played a role.

Tight may not be bad after all – tight may be a beneficial adaptation that we started to get away from when we started to dive into mobility. Just like anything, the sweet spot is usually somewhere in the middle. Everything is great until it becomes the only thing.

I’ve had tight athletes move amazingly + never get injured. And flexible athletes move poorly +routinely get injuries. Flexibility/mobility must not be measured in a vacuum, but are a puzzle piece to the entire coordinative and genetic system of ea. Individual athlete.

— Lee Taft (@leetaft) April 19, 2020

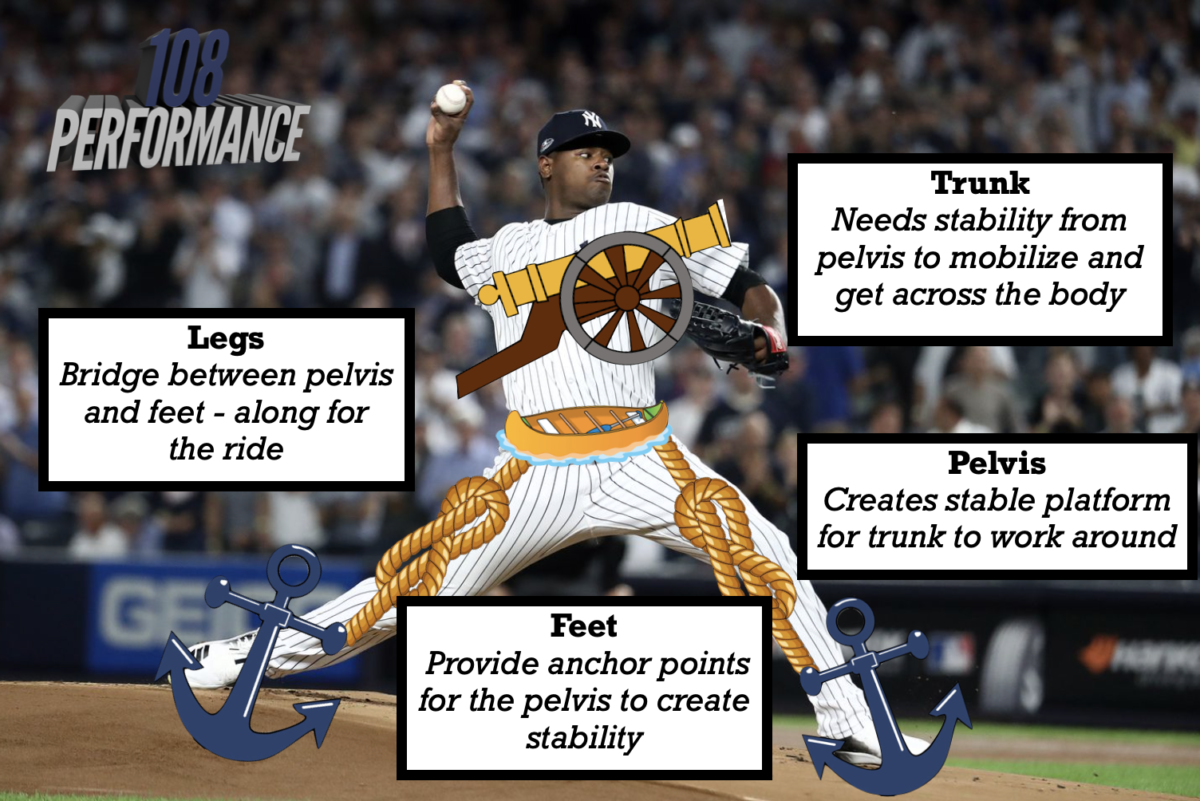

If we go back and pull out the common sense card, the whole reason behind adding mobility is so we can get better at either throwing or hitting a baseball. If adding mobility helps you do either of this, it is beneficial; if it doesn’t, it’s not. If you’re looking at mobility without doing it in the context of the skill you’re trying to hit the dartboard blindfolded; you might hit it every once in a while, but it’s a largely ineffective strategy. Certain areas are going to need to stabilize and mobilize throughout the course of an efficient sequence. If the sequence isn’t where it needs to be, the athlete can’t possibly tap into the mobility they already have. This is why you have to work backwards from the skill: You can’t determine an athlete lacks something if they don’t really know how to use it in the first place. If the pelvis can’t anchor down and create stability for the upper half, adding thoracic mobility is not going to fix the problem; creating a better sequence will.

Now this doesn’t mean we should throw mobility out the window with cookie cutter training programs – we just need to understand it a lot better. Some guys may present with mobility constraints that impact the way they are able to sequence and those must be addressed in coordination with the skill. Everything we do off the field must transfer to what we do on the field. If guys who are increasing their hip mobility are becoming more prone to injury, we need to rethink how we assess athletes and determine how much mobility is sufficient for them. Elite rotary athletes are different; there’s a reason why they represent less than one percent of the world’s population. Trying to fit them into a mold based on how they perform in some bullshit movement screen isn’t enough. We need to understand how those ranges of motion influence efficient movement patterns. I don’t know if we’ve really figure that one out yet – but it’s something we need to figure out if we want guys to perform and stay healthy for a long period of time.

For now, do yourself a favor and think before you start adding mobility – it might do a lot more harm than good if you’re wrong.