See part one of our Bridge the Gap recap here and part two here.

To round out the weekend we were able to put together an MLB players panel which featured Marc Rzepczynski, Cesar Ramos, Tyson Ross, Patrick Mazeika, and Ricky Romero. The five talked about their experiences in player development over the years and what’s had been really impactful on their careers.

For Cesar Ramos, one of his biggest unlocks was realizing he needed to throw his slider more. Ramos featured a four-pitch mix as a player and used his slider the least out of all four. When Ramos played for the Rays, the coaches sat him down and explained to him how the metrics on his slider actually profiled out as one of the best pitches in his arsenal. While it took some time to make this adjustment, Ramos eventually bought in and saw a significant improvement in game performance. This helped him solidify a spot at the big league level and ended up being a huge turning point in his career.

In order to have more positive interventions like these, coaches must be able to share the same information in multiple different ways. This is something Tyson Ross felt was very important when it comes to great coaches. They don’t just describe how to do something one way. They find as many ways as possible to create the same exact movements because they understand the interpretation of information is just as important as the information itself. Him and one of his teammates might be trying to create the same exact movement pattern, but what they need to think about might be completely different. It all works, but not all of it works for everyone.

Knowing what each athlete needs is important, but it’s even more important to know exactly what they don’t need. While Tyson is an athlete that feels very comfortable handling a lot of information and video, Marc Rzepczynski has learned he needs just the opposite. From his experience, Marc realized how looking at too much video or trying to juggle too much information became a crutch because he started to overanalyze his movements on the mound. This caused him to get in his own way and prevented himself from being the best version of himself on the mound. As a result, he’s learned to only focus on one or two things at a time and use what he feels to guide his throwing. When he finds a feel that resonates with him, he tries to recreate it and keep things simple without getting too cerebral. This keeps him athletic and helps him create positive movement adaptations because he’s focused on things that help him have the most success.

“When contact is made, pitchers are in the driver’s seat.” Jerry Weinstein, Colorado Rockies

Outside of the panel, we were very fortunate to have Jerry Weinstein join us for Bridge and share wisdom he’s gained from over 60 years as a coach in the game of baseball. For his presentation, Jerry ran the audience through a simulated inning and broke down each pitch thrown, the result, and what he would have done differently in certain situations. To start, Jerry shared some of rules he uses when he builds out game plans for pitchers and catchers. One of these is the rule of 68: At the MLB level, 68% of all balls put in play are outs. Jerry doesn’t want his pitchers to nibble around the strike zone. He wants his guys to aggressively attack it because the odds are in their favor. Pitchers shouldn’t be afraid of contact. Instead, they should be afraid of falling behind in the count because they’re trying to avoid contact.

During the inning, Jerry brought up a specific pitch during a game between the Arizona Diamondbacks and St. Louis Cardinals. Reliever Archie Bradley was defending a 9-5 Arizona lead in the top of the ninth with runners on first and third and Rangel Ravelo at the plate for St. Louis. With a 1-1 count, Bradley decided to throw a curveball in the dirt that Ravelo took for ball two. In Weinstein’s opinion, this pitch was a mistake because 1-1 is a big count to win (MLB BA swings around .200 based on result of pitch). Pitchers need to throw their highest percentage strike pitch to their highest percentage strike location. Instead of throwing his best pitch (fastball), Bradley throws his curveball which only lands in the zone 23% of the time. This becomes an easy take for Ravelo and sets him up in a hitters count with runners in scoring position. If Weinstein was calling pitches, he would have had Bradley challenge Ravelo with his best fastball considering Bradley’s strengths, weaknesses, and the current situation (four run lead).

“I’m here to tell you asymmetries are okay until you can’t function or reciprocate.” Ken Crenshaw, Director of Sports Medicine & Performance Arizona Diamondbacks

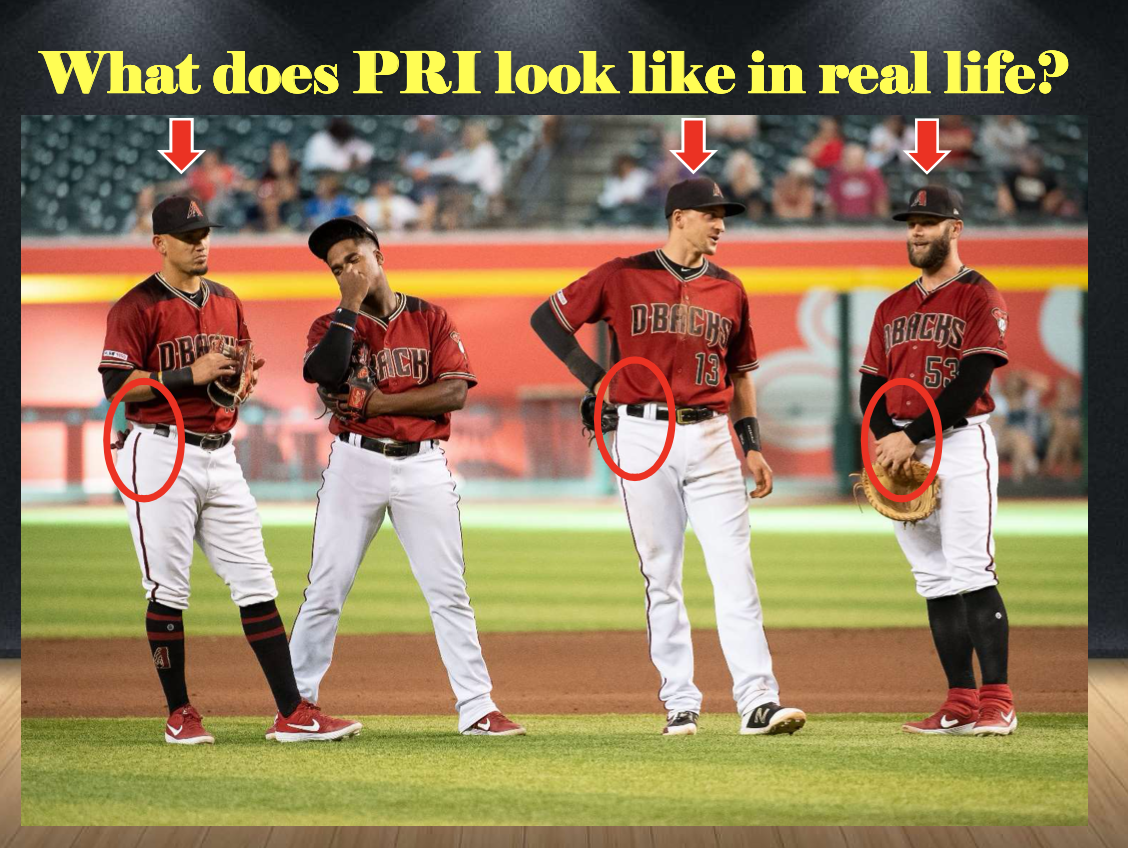

Ken Crenshaw – Director of Sports Medicine and Performance Arizona Diamondbacks – was also able to join us and deliver a presentation on his thoughts around training the core. One of the big points he drove home in his presentation was the myth around asymmetries. While we typically think of asymmetries as a barrier to performance, Ken argued that asymmetries are actually very normal. Internally, our bodies are not symmetrical at all. Our liver, colon, and appendix are all on the right side of our body and our stomach, heart, and spleen are on the left. This internal imbalance causes us to naturally fall into asymmetrical patterns, as seen below. These patterns are completely okay and shouldn’t raise red flags – as long as we can check a couple of boxes.

Instead of looking at symmetry, Ken looks to see if his athletes are able to function. If they can execute basic motor tasks and swing or throw without pain, he doesn’t place too much stock in the asymmetries they present with. After all, baseball is largely an asymmetrical sport. The majority of us only swing or throw from one side. This doesn’t mean we should completely negate asymmetries and the role they play in influencing movement, but it does mean we need to look at them through a different lens. Asymmetries by themselves are not a problem. How those asymmetries influence motor function is what we really need to look at.

Lastly, we were able to have Darin Everson – Hitting Coordinator Colorado Rockies – hop on and share his thoughts on developing efficiency in hitters. For him, three things stand out:

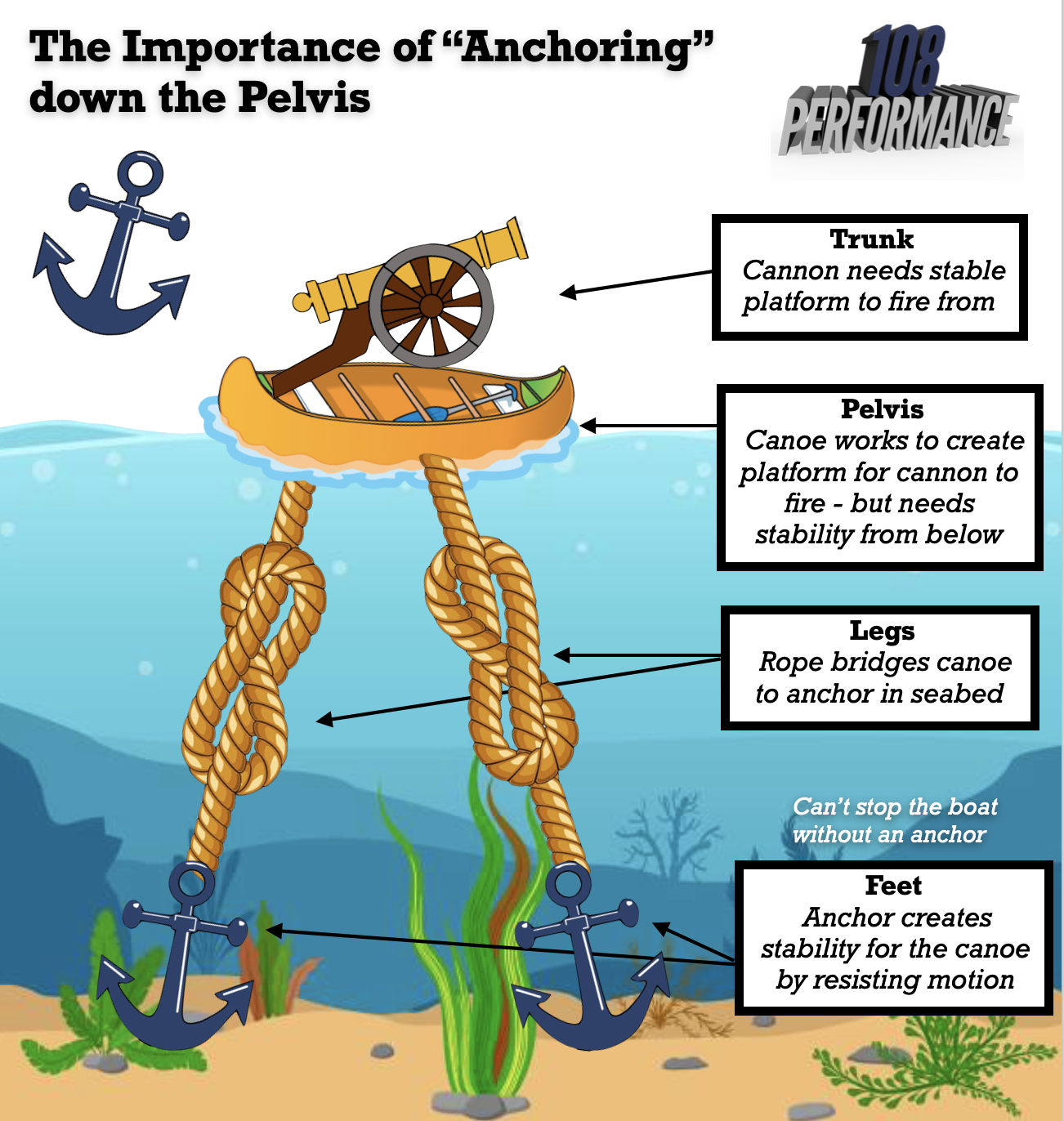

- Are they anchored into the ground?

Hitters who move really well are able to use their feet as “anchor points” to create stability for the pelvis. This gives the trunk the platform it needs to rotate around and reciprocate against the lower body. If hitters aren’t able to create a stable connection to the ground, their pelvis becomes unstable and energy leaks are created. A big part of hitting is being able to move a weight through space as efficiently as possible by moving to and through strong positions. Paying close attention to how guys interact with the ground gives you a lot of information on their ability to do this.

- Can they stop and produce force in small windows?

Hitters have a small window of time and space to produce force given the constraint of the incoming pitch. As a result, just producing a lot of force isn’t as important as how quickly it can be transferred and applied up the chain. Whether we can do this or not depends on our ability to put on the brakes. The next segment cannot accelerate until the previous one has decelerated. Thus, an inability to stop hurts your ability to go.

- Do they have space to work? Are they compensating to create this space?

All hitters need space and room to work so they can get their best swing off consistently. Some common ways hitters do this include hinging, staying closed, or clearing the lead arm as the hands make moves to the ball. However, all space is not created equal. There are numerous compensatory patterns hitters will pull off to make up for the space they lost earlier in the sequence. An example of this would be a hitter who opens up with their pelvis too soon and has to pin their hands up against their body to prevent them from peeling off the baseball. They might be able to create enough space so their swing can work, but how they create it isn’t optimal.

It’s like TCU strength coach Zach Dechant talked about in Part II: The best athletes are often the best compensators. The solutions they come up with work, but it doesn’t mean they’re the best solutions.

Interested in more? You can get full access to all of the BTG20 presentations here.